Pew: Four percent of Philadelphia census tracts gentrified from 2000-2014

How much gentrification is really taking place in Philadelphia, and how much are residents worrying about this?

In neighborhoods surrounding Center City and University City, the sense of rapid change is palpable, as new higher-end amenities pile up by the week, and ubiquitous scaffolding leaves some communities feeling like big construction sites.

The topic tends to inspire heated debates, with strong overtones of race and class conflict, but these debates have until recently taken place in a relatively fact-free zone, with little context available to help residents wrap their arms around the scale or the scope of change.

Last year that began to change, with the Philadelphia Fed releasing the most comprehensive look yet at the connection between gentrification and displacement in the city, and now a new report from Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative aims to identify to how intense the phenomenon is locally, where it’s taking place, and how residents feel about the changes.

Defining gentrification

Every facet of gentrification is hotly disputed, perhaps none more than the definition. Some insist the phenomenon should be defined in terms of income, while others prefer to focus on racial aspects, housing prices, or the types of businesses in an area.

Pew went with an income-based model, reasoning that income data was more robust than information on housing prices and rental rates, and they defined gentrification as occurring when a neighborhood’s demographic make-up shifts from a lower-income population to a significantly higher-income one.

Three factors were used to determine whether a Census tract had gentrified:

– A median household income in 2000 below 80 percent of the regional median income of $53,992–a key eligibility threshold for many federal low-income assistance programs

– An increase of at least 10 percent in the tract’s median income, in inflation-adjusted dollars, between 2000 and 2014

– A 2014 median household income exceeding the citywide median of $37,460

If a tract had all three of these, it was considered to have gentrified. Pew’s study only looked at more recent trends, so tracts that gentrified prior to 2000 were excluded.

A limited trend

Pew is careful not to minimize the impact of change in the places where they determined gentrification has taken place, but their findings indicate the scope of the phenomenon is more constrained than some might expect, given the level of attention it receives in the media.

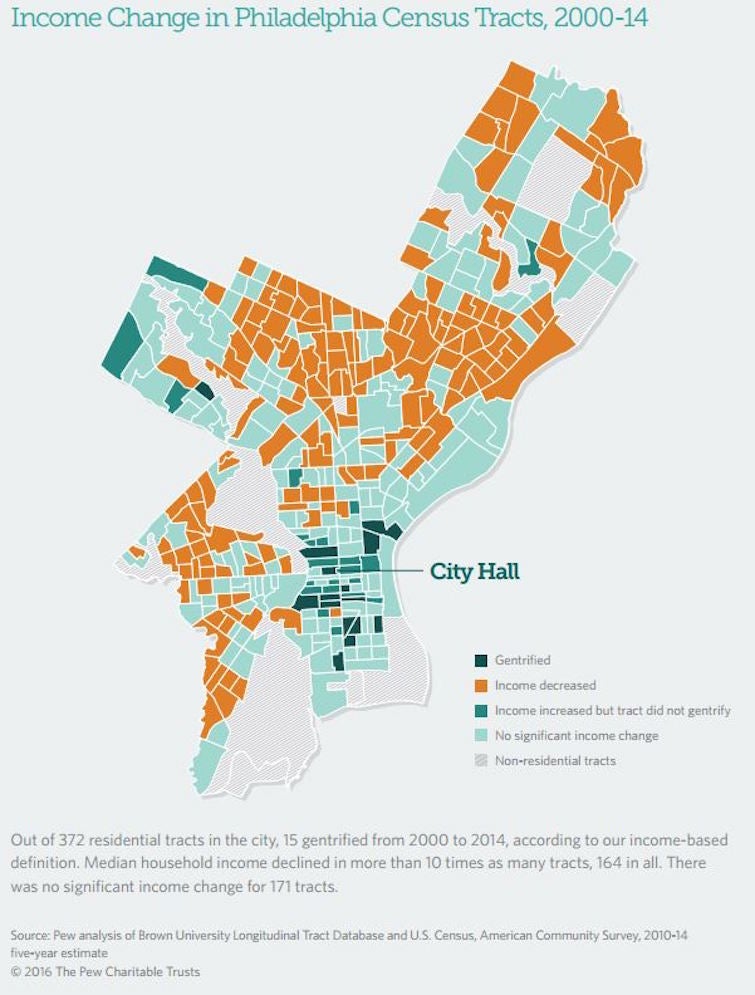

According to Pew’s definition, only 15 of Philadelphia’s 372 census tracts, or 4 percent, gentrified between 2000 and 2014. Those tracts were located mostly in South Philly, Center City, and just north of Center City. None were in the bottom quarter of the city’s census tracts for income in 2000, and 12 had higher percentages of white residents than the city as a whole to begin with. In 2014, most of these remained more middle-income than high-income.

By far, the more significant trend in the city between 2000 and 2014 was falling income and disinvestment, with 164 census tracts experiencing statistically significant decreases in median household income over the same period – more than ten times the amount to have gentrified.

The number of Philadelphians living in poverty increased by more than 60,000 during that span, underscoring the extent to which Philly is not experiencing the scale of metro-wide gentrification seen in New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Pew notes that several other parts of the city experienced changes associated with gentrification, like growing housing costs, increasing education levels, and changing racial demographics, but which did not see increases in income.

As a comparison, the Philadelphia Fed’s recent study from December 2015, which used a different definition of gentrification that included changes in housing costs and education levels as well as income increases, found that 56 census tracts gentrified between 2000 and 2013.

Whether it’s 4 percent of 15 percent though, it’s clear that many more areas of the city are experiencing a problem of deepening poverty than are seeing jarring influxes of higher income residents.

A taxonomy of Philly gentrification

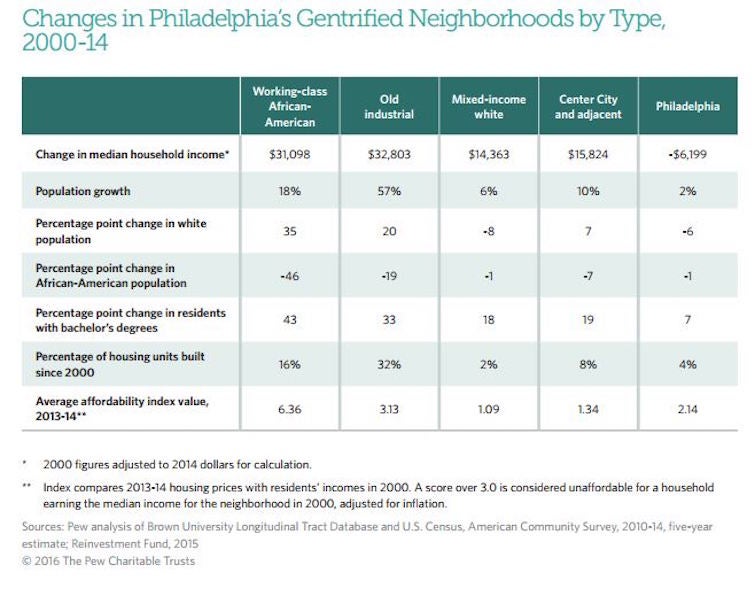

The phenomenon doesn’t always play out exactly the same way everywhere, so Pew categorized neighborhoods into four different types, based on their characteristics prior to 2000.

They include neighborhoods that had primarily working-class, African-American populations; mixed-income, mostly white population; old industrial areas with relatively few residents; and non-affluent sections of Center City and nearby neighborhoods.

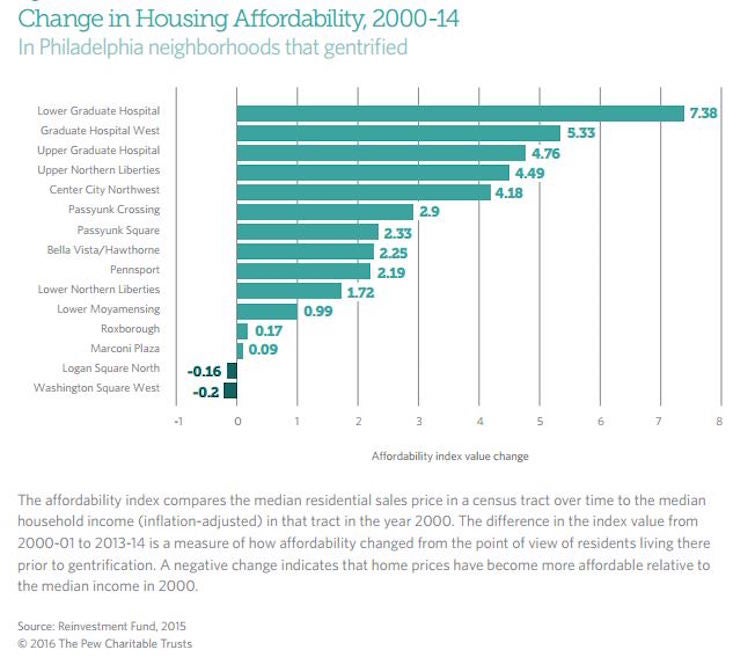

The predominantly working-class African-American neighborhoods that gentrified were limited to three census tracts. All of these were in Graduate Hospital, and the changes were extreme.

The total black population for these three census tracts fell from 7,793 to 3,450 between 2000 and 2014, during which period the white population tripled from 2,156 to 7,007. That’s a pretty complete neighborhood turnover, in a way that is atypical for even the other gentrified neighborhoods.

“Living in these tracts became largely unaffordable for the people who had been living there in 2000, as measured by Reinvestment Fund’s affordability index. According to that index, the home price-income ratio rose more in Graduate Hospital than in any of the other gentrified areas,” the report says.

Home prices rose the most in areas with higher number of investor-owned and vacant properties in 2000, which were concentrated in the working-class African American and old industrial categories. Home prices rose more than 1,000 percent in one tract.

Mixed-income white neighborhoods with fewer investor-owned or vacant properties didn’t see such extreme changes in real estate prices, with median prices in those tracts all staying below $300,000 in in the 2013-14 period. Home prices citywide recently hit post-recession highs, with big changes happening in just the last couple of years, so this will be interesting to revisit as data from 2015 and 2016 becomes available.

Another interesting finding: Point Breeze was not considered to have gentrified during the study period.

“The changes in Graduate Hospital have fueled development-related tensions in Point Breeze, the mostly African-American neighborhood directly to the south, which did not gentrify during our study period but has undergone substantial change in the past few years,” the report says, “Objections there have focused on the scale, speed, and price point of new construction and the target audience of new businesses.”

Gentrification is popular

What are Philadelphians making of all this?

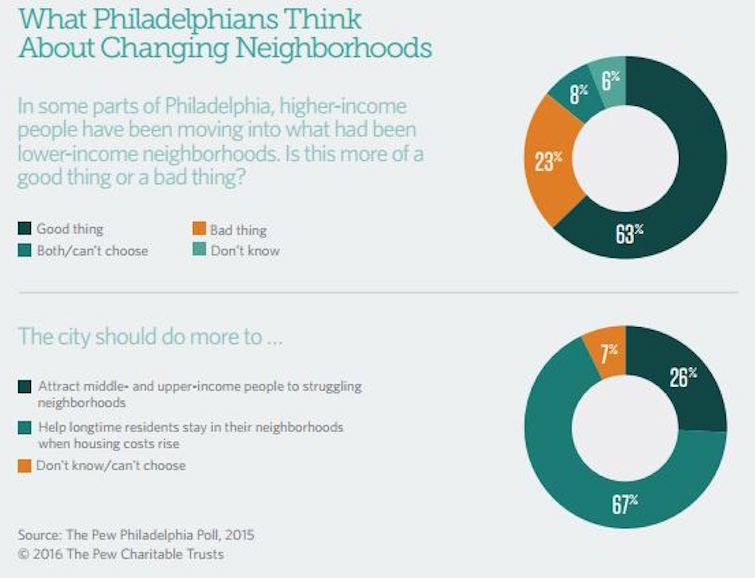

The G-word tends to make people retreat back to hardened opinions, so Pew tried polling the issue using less loaded language, describing the trend rather than naming it.

Instead they asked: “In some parts of Philadelphia, higher-income people have been moving into what had been lower-income neighborhoods. Is this more of a good thing or a bad thing?”

Fully 63 percent of respondents said this was a good thing, and only 23 percent said it was a bad thing. Eight percent had mixed feelings, and 6 percent said they weren’t sure.

Of those polled, 74 percent of whites, 65 percent of Hispanics, and 55 percent of African-Americans agreed it was positive for higher-income residents to move into lower-income neighborhoods.

Pew also posed a question with more of a policy bent, asking whether the city should do more to “attract middle- and upper-income people to struggling neighborhoods” or “help longtime residents stay in their neighborhoods when housing costs rise.”

By a margin of 67-26 percent, respondents said helping longtime residents stay in their homes was the better approach. Seventy-two percent of residents living in the city 30 years or longer selected that option, while residents of 10 years or less supported this view by 56 percent.

In the grand scheme of things, Philadelphians see gentrification as a fairly low-priority policy issue, with only 5 percent of poll respondents identifying it as the biggest issue facing the city, far behind education, safety, and jobs.

Overall, the typical Philadelphian seems to be generally supportive of the changes reshaping the city’s centrally-located neighborhoods, but skeptical that they need an extra helping hand from the city, such as the 10-year tax abatement for property improvements.

Read the full report and explore the multimedia features on Pew’s website for a more detailed explication of demographic and housing trends in Philadelphia’s changing neighborhoods, and their lessons for policymakers.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.