Pennsylvania does not protect workers as well as it should

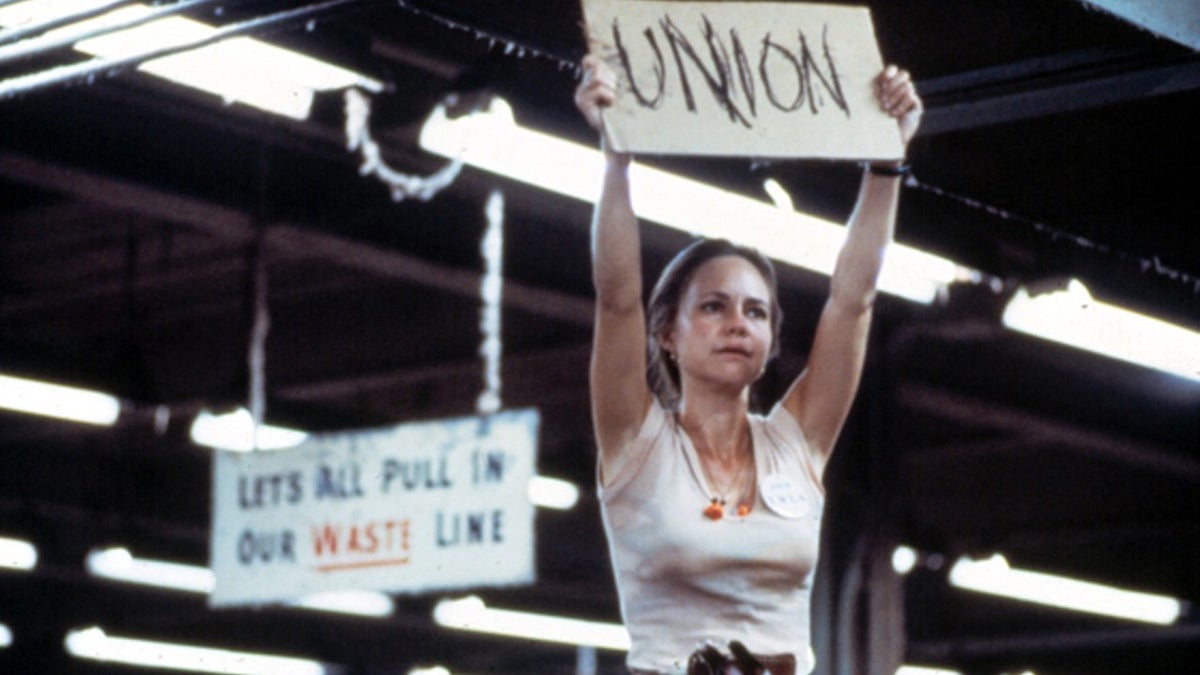

Actress Sally Field as Norma Rae is shown in this still from the eponymous 1979 film about a woman who stands up against her employer's unfair labor practices.

In the midst of today’s ongoing disputes about a fair living wage, pay equity for women, workplace protections for LGBT employees, and the unemployment crisis, I think a re-evaluation of at-will employment policy is more relevant than ever.

I was born at the the worst time to enter the job market. After college, I entered an economy that had been ruined by the mortgage crisis and stock market crash of 2007-2009. The world was witnessing the fallout of capitalism run amok.

For years, I have had to work odd jobs to scrape together a living: service jobs, construction, mopping floors, scrubbing dishes. I went door to door. I held menial office positions. I did every kind of work imaginable.

I was just becoming accustomed to working for a living, and as such, I was progressively learning what the laws of Pennsylvania afforded me and required of me. At each job I held, it seemed that in some particular way, I saw what I believed to be my natural rights as a laborer undermined.

Learning the ropes

At the same time, I became increasingly aware of the detachment and complacency of the American workforce. One example that stands out in my mind is Pennsylvania’s policy concerning how many breaks workers can take during a shift. I once had a job that did not allow staff to take any breaks. I asked one of my co-workers, “Is that legal? How could it be? It would controvert hundreds of years of labor struggle.”

To my astonishment, not only did she not know what the law was, but she had never even thought about it, and she didn’t seem to care.

So I checked for myself. I discovered for the first time that neither federal nor state labor laws require employers to provide adult workers with any break time during their shift.

At a later job, I told a co-worker about this while we sat in the back room. She assured me that I was mistaken. She pointed to the posters on the wall outlining federal and Pennsylvania labor laws. Having already read them, I asked her to show me the sections she was referring to. To her surprise and confusion, they were not there.

It made me sad to think that this well-meaning and intelligent employee had seen posters on the wall and taken for granted that her government provided her with a basic set of rights — because she had never thought to read them.

A stranger in my own land

This situation was telling, but it was a relatively minor concern. A more deeply troubling labor regulation to me is far more entrenched and widespread — that of at-will employment.

This employment contract states that employers are not bound to provide a reason to dismiss an employee, leaving an individual’s employment at his or her boss’s whim. In the midst of today’s ongoing dispute about a fair living wage, pay equity for women, workplace protections for LGBT employees, and ending the unemployment crisis, I think a re-evaluation of this mandate is more relevant than ever. Job security must be an equal consideration. I come to this contention from personal experience.

During my undergraduate studies, from 2006 to 2007, I lived in France, where I experienced and participated in a general strike against the passage of a new labor contract called the CPE (Contrat de première embauche — “first labor contract”). The law decreed that workers below the age of 26 would begin employment on a two-year “trial period,” during which time the employer would have the right to dismiss them without having to cite a reason.

This was unheard of in France. The people took to the streets in outrage, saying that the new law rendered their employment “precarious.” I remember one protester shouting out that his people were “losing their future.” They walked out of work, blockaded the universities, created barricades, and stopped street traffic and trains. It was the largest national strike since May 1968.

One day, a fellow protester remarked offhandedly, “I think this law is coming to us from the United States.” I was a teenager at that time and had not yet really begun to work for a living, so what he said surprised me. But I didn’t know enough to contest it.

Years later, of course, I discovered that he was right. The flagrant violation of French labor rights that we had opposed was, in my own country, commonplace and unchallenged. It was merely because of my experience abroad that I realized it could even be considered objectionable. Indeed, the only difference in the U.S. is that the possibility of dismissal with or without a valid reason applies to all workers regardless of age, and is applicable for the duration of their employment, not just two years.

As it is worded in the Supreme Court case of Witkowski v. Thomas J. Lipton, Inc., “[a]n employer may fire an employee for good reason, bad reason, or no reason at all under the employment-at-will doctrine.”

As attorney John A. Gallagher explains, the only form of security workers can hope for is that their employment is unionized. “[I]f you are a member of a union,” Gallagher writes, “you generally cannot be terminated unless there is ‘good cause’ for the termination, and unless the company first goes through a progressive set of disciplinary actions.

“That’s not true for the rest of us,” he continues. “The rest of America — the non-unionized portion of America — remained without any protection (unless they fell into the rare category of employees who have a contract for a specified period of time, which in many cases is limited to sports figures and top-level executives).”

The distribution of security for employers and employees is imbalanced. What if a police officer could arrest a citizen, or a landlord could evict a tenant, or a university could dismiss a student, “for good reason, bad reason, or no reason at all?” Any such laws couched in this language would be intolerable.

Unless the firing is deemed an act of discrimination on the basis of “race, gender, national origin, disability or age,” or if the employee is pregnant or qualifies among a handful of other exceptions, there is no legal recourse.

‘Discrimination,’ a fluid term

Aside from the difficulty of proving such discrimination in court, these stipulations leave one group in particular glaringly vulnerability: LGBTQ communities. In recent years, I have followed the push for the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, which sought to protect workers from discrimination because of their perceived LGBTQ orientation. The act has since been expanded into the Equality Act, a comprehensive civil rights proposal for LGBTQ people including employment, housing, and business protection among a host of other provisions.

Americans for Workplace Opportunity, a national NGO that advanced the cause of ENDA, stated that “this is one of the most important issues facing our society today. Every day, LGBT Americans across the country face serious risk of discrimination in employment, including being fired from a job, being denied a promotion, and experiencing harassment on the job.”

In 28 states, including Pennsylvania, this kind of discrimination is still perfectly legal.

Ultimately, I believe the only means of doing away with all forms of discrimination in the workplace is to create a labor contract that guarantees a degree of job security. In the current American workplace, in which “just cause” is virtually nonexistent, the ability of employers to discriminate can persist despite protections for individual groups.

Individuals are left to look out for their own interests and for those of their fellows. If we leave gaps in our employment rights, many employers will seize upon every one of these gaps to abuse them. And it is only through action that such abuses can be put to an end.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.