Pathway to greener pastures: Philadelphia presents plan for a litter-free city by 2035

It may be hard to imagine, but if Philadelphia succeeds in implementing its new and comprehensive Zero Waste and Litter Plan, the city’s infamous nickname Filthadelphia may be completely obsolete in less than 20 years.

Maybe.

This Monday, after a month of delay, the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet — an inter-departmental group created by Mayor Jim Kenney in December 2016 to achieve its zero waste goal — presented a major road map to reduce the amount of waste Philadelphia produces and to increase the amount it recycles by 90 percent by 2035.

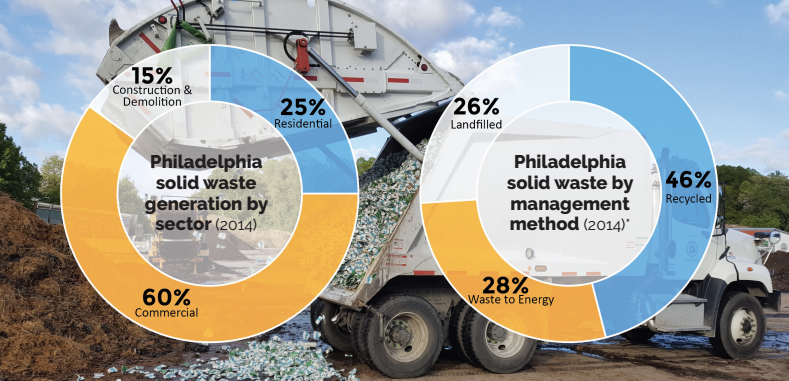

Every year, Philadelphia disposes 1.5 million tons of residential and commercial waste — one ton for every resident. Reducing that waste — or diverting it through alternative disposal methods that can recycle or reuse the refuse— would save the city $41.5 million dollars annually, city officials said.

“To dispose waste we pay $35 million dollars a year,” Philadelphia Department of Streets commissioner Carlton Williams said. “Currently, we’re paying to recycle — it fluctuates but — around $3. And we’re spending $60-a-ton when we throw it to waste trash [landfills or incinerators].”

“Diversion is extremely important — not only is it good for the environment — there is an economic benefit for it as well,” Williams said.

On top of that, the city spends $8 million annually cleaning up illegal dumping.

“Can you imagine how better city services would be if our workers didn’t have to go out and clean up dumps all the time? If sanitation workers were freed-up to work on other projects?” Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet’s director Nic Esposito said.

Esposito said in some parts of the city, Department of Parks and Recreation’s workers spend about 60 percent of their working time picking up trash. “Can you imagine how nicer our parks would look, how better Rebuild would be, if we can [stop] people dumping in our parks?”

Philadelphia’s Managing Director and Chair of the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet Michael DiBerardinis believes the plan relies on a social compact, a voluntary agreement between residents and city government for mutual benefit.

“If we can kick up the recycling — through education, through people understanding the value that this accrues to the city, [through] the diminishing of litter and waste of all variety— it really begins to build this… we need this sort of civic compact between the government, big institutions, businesses and the citizens.” DiBerardinis said. “This idea of shared responsibility is really important. And I think without it we won’t do as well. If we can do it well, I think we’ll have a much better chance of reaching the ambitious goals of the plan.”

Litter-free by 2035

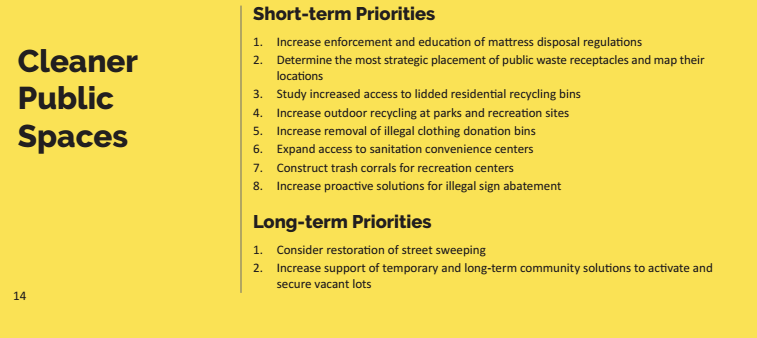

The Zero Waste and Litter action plan includes 31 short and long term recommendations for regulations, policies and ordinances to make Philadelphia litter-free. The document doesn’t only present them as a list, but includes the feasibility and effectiveness study behind each one of them.

The list’s number one problem to tackle? Illegal dumping. Recommendations include increasing short dumping fines from $300 to $2,000 (legislation is pending in City Council; fines have not been increased since the 1980s), improving surveillance at common short dumping sites, imposing seizure of vehicles involved in dumping crimes, and requiring contractors to provide waste plans when they pick up construction, demolition or alteration permits.

“It has to stop,” Esposito said. “It’s demoralizing. People clean up a lot and then sometimes later that day it gets dump[ed on] again. And when people see that, they say, ‘Ok this doesn’t work, I don’t care anymore, I’m not cleaning up.’”

Many anti-littering regulations are already in place; the cabinet’s goal is to increase enforcement. One of the long term goals is to create an environmental crimes unit in the Police Department, with more officers and resources exclusively dedicated to enforce these regulations. And to increase and streamline illegal dumping cases in court.

In 2016, only 12 short dumping cases were charged as misdemeanors. That year the Streets department cleaned 921 short cumps and CLIP investigated 128 cases, according to the cabinet.

“It’s a major problem; it’s probably the biggest problem that focuses and causes litter conditions in any neighborhood,” Streets commissioner Williams said. “We have to start getting people not to treat our city like a trash can.”

The plan also recommends restoring street sweeping, banning plastic bags, placing more trash receptacles, expanding the access to sanitation convenience centers (the city’s public dumps), and mandating that all circulars are designed as door hangers.

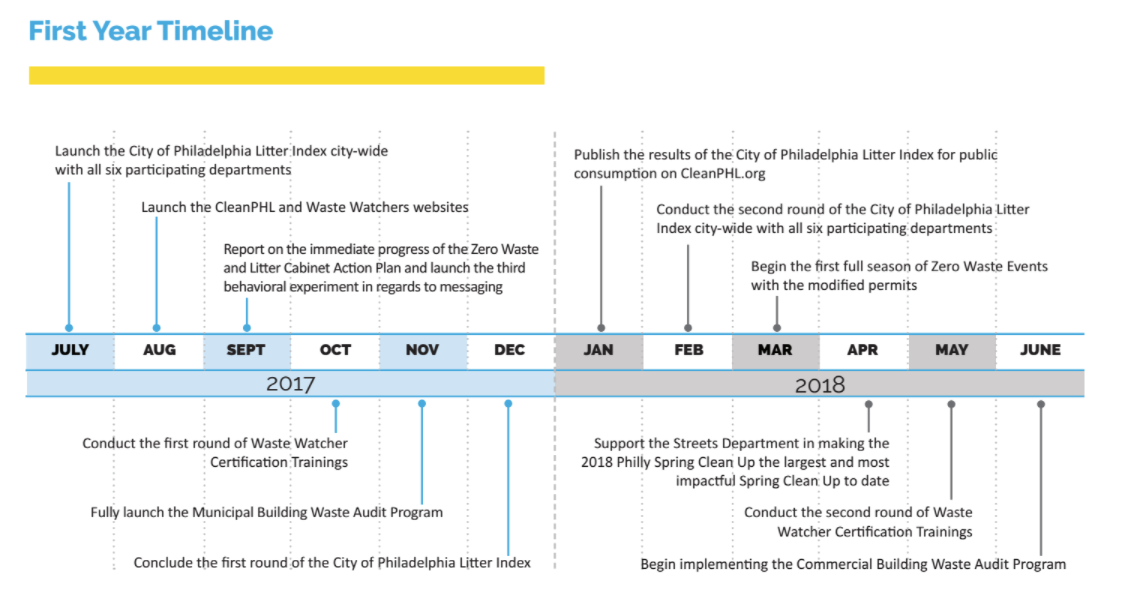

An important aspect of the plan is data. The cabinet believes geo-located data and specific information will be crucial in guiding their policy and investment decisions, as well as measuring their effectiveness. DiBerardinis said one of the most revolutionary aspects of the plan is a city-wide litter index.

“We’ll know how much litter is an particular block, what’s the makeup of that litter, and hopefully where it came from,” DiBerardinis said. “So we’ll be able to take a picture of almost every block in the city of Philadelphia and understand the litter situation on these blocks. It’s a really important piece of data.”

The litter-index, which was piloted in Port Richmond and Brewerytown this spring, relies on data collected by the Streets Department, Community Life Improvement Programs (CLIP), Parks and Recreation Department, School Department, Water Department, and SEPTA.

According to the plan the surveyors will count “each piece of litter on a city asset or property” and provide a litter rating from 1 (little to no litter) to 4 (a lot of litter).

Part of the plan is releasing the website CleanPHL.org where residents can check the litter situation on their blocks, coordinate action and find resources available.

“I think the most important aspect of the plan is that it allows people to engage with government and we can partner together to solve an age-old problem that we’ve been trying to solve for decades [litter],” Williams said. “And so together and holistically we can use multiple agencies — it’s not just the Street Department, it’s not just CLIP, it’s not just Licences and Inspection — but it’s the entire city government working with residents.”

Reducing waste, increasing recycling

The zero waste plan set strategies to reduce the amount of waste the city sends to landfills and incinerators to zero by 2035. The goal is to reduce waste generation and increase waste diversion by 90 percent by then, with an estimated 10 percent of non-recyclable items — like the packaging for chips and other snacks— that would be sent to incinerators with the capacity to produce energy, known as waste to energy plants.

Currently, the city diverts approximately 21 percent of the 623,474 tons of waste it collects a year, according to data from the Philadelphia’s Streets Department. If you include private collection, the diversion rate goes up to 38 percent.

“There’s still a long way to go and we think that people can do more,” Streets commissioner Williams said.

One of the four strategies for waste reduction is engaging the public through a Zero Waste Partnership Program developed by the Street Department. It will expand the recycling award program — rebranded as Waste Watchers Rewards — and give grants to community-based orgs for initiatives that increase community access to recycling and ensure greater participation in picking up and preventing litter.

“If we incentivize them [residents] to do it [recycle more] by rewarding them with points that they can then spend in our local economy, and have businesses to partner, we believe people would begin to manage their waste even more,” said Williams.

Another recommendation to increase recycling at a residential level is to give away lidded bins. A lack of recycling bins keeps some people from recycling, the plan says. And the unlidded blue bins the city currently provides can increase street litter on windy days.

City officials said another key component for waste reduction is purchasing products that last longer and are recyclable or compostable.

“One of the key components of the plan is to not only look at waste once it’s discarded but to look at the entire lifecycle of a product,” Williams said. “Being the 5th largest city in America, we have a lot a buying power to influence things.”

The city will also start a Building Waste Audit Program to make sure municipal and commercial buildings comply with existing recycling and waste management regulations. According to the Zero Waste plan, many municipal buildings are not in full compliance with Executive Order 5-96, which requires them to offer recycling options. Only 22 percent of commercial buildings have a complete recycling plan.

Another waste reduction and diversion strategy is the Zero Waste Events Program which will modify special events permits to include a recycling mandate and recommendations.

To increase organic diversion — keeping food and yard waste out of landfills by means of composting and other alternative disposal methods — the Zero waste plan recommends enacting city-wide composting collection and to expand non-single stream recycling options for residents and businesses.

The Philadelphia Streets Department estimates that food waste constitutes 18.3 percent of the municipal solid waste that ends up in landfills, about 240,609 tons of food waste per year. Considering yard waste and others, organic waste makes up about 30 percent or municipal waste.

The Streets Department is conducting a study to determine exactly how much organics the city send to trash, the capacity it has to recycle them — through composting and anaerobic digesters — what would it mean to offer city-wide collection, and evaluate if there’s a market for the products. The results of the feasibility study will be published later this summer.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, the Zero Waste plan is partnering with experts from local academic institutions to develop studies to understand the who, what, how, and why of litter.

And because changing behaviour is the biggest challenge the Zero Plan has, education will be key.

“We’ve created a throwaway culture,” Esposito said. “Whatever happened to washing a dish when you had people over? People are using paper products in their house when you have dinner, you know. We’re putting out, curbside, three times the amount of waste that we did in the 1960s. That’s a huge problem.”

Zero Waste starts with one, says the plan’s marketing campaign. City officials said the only way to get rid to Philadelphia’s litter and trash is with everyone’s participation.

Philadelphia has set a goal to become a Zero Waste city by 2035. Throughout 2017, PlanPhilly will report on ways the city is working toward that goal by looking at the opportunities found in the waste stream – from compost to cogeneration, recycling to gleaning.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.