Paintings depicting Panama Canal construction in dramatic detail on view in Doylestown

ListenAn expanded Panama Canal opened last week, allowing larger cargo freighters to slip between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Its progress could be tracked through time-lapse video on YouTube.

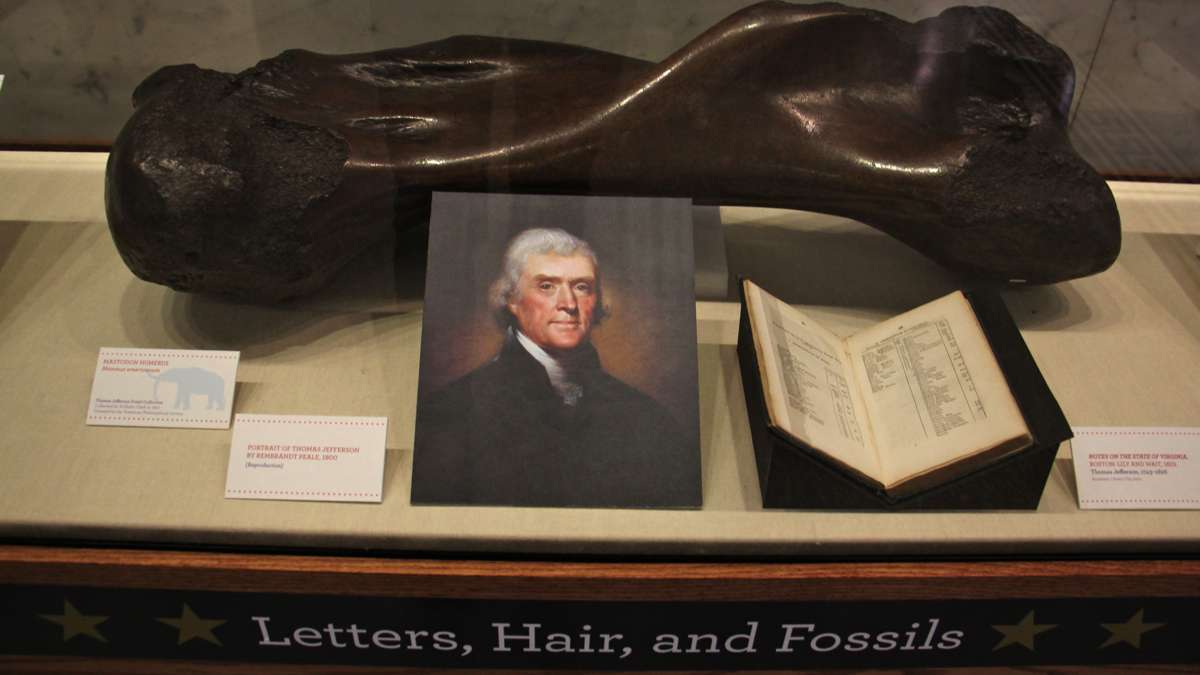

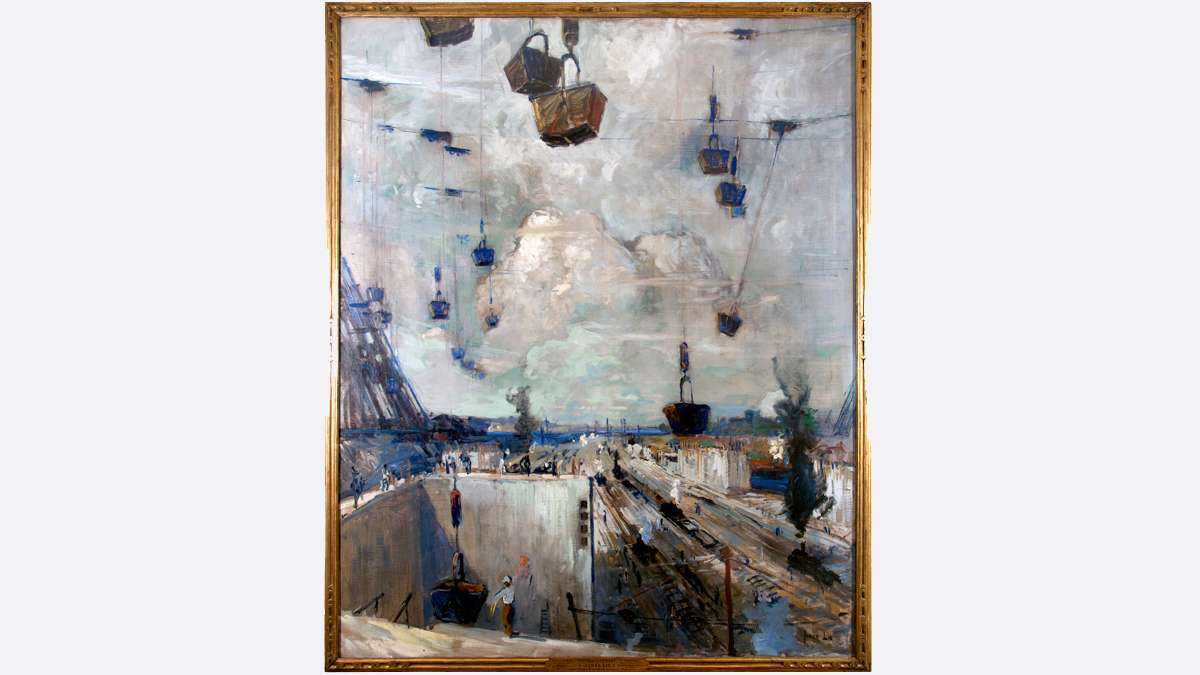

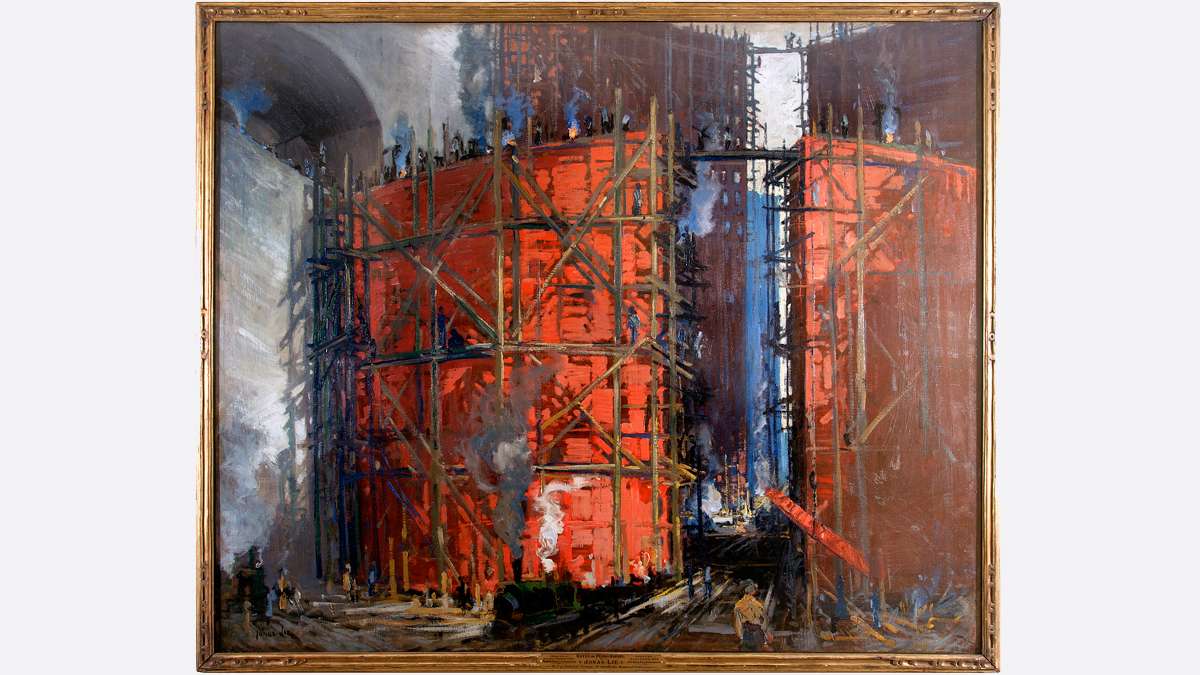

The first time the Panama Canal was dug, a century ago, it was documented in paint. The paintings of Jonas Lie are now on display at the Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

Lie was Norwegian by birth, a New Yorker by trade, and in Panama by adventure. He had been making a name for himself painting scenes of urban New York, particularly the city’s working harbor. But he became entranced with the construction of the Panama Canal in 1913 after seeing a very early color film in Carnegie Hall. While the American market already had plenty of sketches and photography of canal construction, “The Making of the Panama Canal” (1912), which no longer exists, inspired Lie to seek the spectacle of scale and color.

“He’s interested in the poeticism, the romance, the drama of the construction,” said Kirsten Jensen, curator at the Michener Museum. “This incredible struggle of man against nature.”

Man lost his first struggle against nature. The French first attempted to carve a 50-mile slice through the Panama isthmus in the late 19th century. After 20,000 workers died — mostly from malaria and yellow fever — they abandoned the project.

The Americans took up the challenge shortly after, in 1904, armed with massive sanitation efforts and a proactive plan to eradicate mosquitoes. Ten years later, the canal was finished. To this day, the area is effectively free of malaria and yellow fever.

Lie spent several months in the cut alongside workers, painting on a portable easel. He rendered the gates of Pedro Miguel, a massive, bright-red water gate still covered in scaffolding. He also painted baskets of concrete delicately lowered on wires into a 1/2-mile-wide man-made canyon, seeming to float against a bleached sky.

“The techniques of construction reflected ancient Roman aqueducts. He was translating an ancient past into a new future,” said Jensen. “He was really interested in conveying the awe and the sublime wonder that industrial and technical developments in the early 20th century had.”

Lie came back to New York and exhibited 28 large-sized canvases, painted in expressive brushwork. The images are less about how the canal was built, more about what it felt like to built it.

“People loved this show,” said Jensen. “When it first opened in Knoedler gallery in New York, more than 1,000 people saw it, which is a phenomenal number for an opening day of a gallery exhibition.”

The paintings later traveled to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, nobody wanted to buy them. Only two canvases were sold. Lie held onto the rest for 15 years, when they were ultimately sold as a set and donated to West Point.

As for Lie, he turned away from jungles and heavy machinery for his next painting adventure. After Panama he sailed back to his homeland to quietly paint landscapes of Norwegian fjords.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.