PAFA displays Black art collection of Constance Clayton, former Philadelphia school superintendent

Constance Clayton has been collecting African American art for 30 years. She recently gave much of her collection to PAFA in Philadelphia.

'Awakened in You,' an exhibit at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, celebrates the gift of Dr. Constance E. Clayton, a collector of African American art and former superintendent of Philadelphia public schools. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

After receiving a substantial gift of African American art last year, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is now exhibiting 76 paintings and sculptures that came from the personal collection of the former Philadelphia School District superintendent, Dr. Constance Clayton.

Clayton was the first African American woman to be Philadelphia’s school superintendent, holding that position from 1982 – 1993. Toward the end of her tenure, she began collecting art with her mother, Williabell Clayton.

The mother and daughter duo wanted to acquire work specifically by African American artists, combing galleries and antique stores with an eye for things that would look good in their shared Mt. Airy home.

She also wanted work that told a story or conveyed a message about African American life.

“If I’m going to live with it, I want to like it,” Clayton said. “I don’t want to buy it because it has someone’s name on it.”

Clayton continued to collect art after her mother died in 2004, amassing about 300 pieces, including landscapes, domestic scenes, portraits of Black families and children and abstract works.

“I love the brilliance of the colors,” Clayton said.

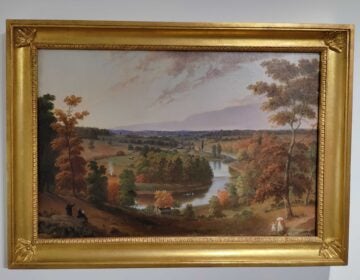

The collection includes minor works by major artists: sketches by Henry Ossawa Tanner and Charles White, a rare charcoal by Barkley Hendricks, two 19th century oil landscapes by Edward Bannister. They are all modestly sized. Most of the collection could be squeezed onto the walls of the Clayton home.

“As a museum director, it is always the most gratifying thing to hear that a collector collected what they liked,” said Brooke Davis Anderson, director of PAFA’s museum. “We know, in the 21st century, collecting has changed a lot in the contemporary art sector. But collecting art because you want to live with it is, at [its] core, a very admirable approach to art collection building.”

When Anderson was invited to visit the Clayton home last year to acquire items for PAFA, she found that they had assembled a serious collection.

“I think she and her mom were specifically creating a collection that marched us through the history of African American art,” Anderson said. “Because that’s what this does.”

The exhibition, “Awakened In You: the Dr. Constance E. Clayton Collection,” features an entire wall of works by Dox Thrash, the painter and printmaker who benefited from the Works Progress Administration to make work about Black laborers in the Philadelphia shipyards. There is also an etching of Walter Edmund’s young son. Edmunds is known for the murals inside the Church of the Advocate in North Philadelphia.

There are two paintings by Laura Wheeler Waring: a portrait of a young Black student in a pensive pose and a group portrait of four Black children. Waring taught for 30 years at Cheyney University and now has a Philadelphia public elementary school named after her.

There is a sparse, abstract print by John Dowell, who taught at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art. The piece doubles as interpretive sheet music (the marks can be read as notations for extended performance techniques, à la John Cage) . There are several small landscapes by Louis Sloan, who taught at PAFA.

Not surprising in a collection assembled by an educator, there are lots of teachers represented here. One of Sloan’s students was Barkley Hendricks, who would become well-known for his full-body portraits of African Americans in 1970s hipster clothes.

Hendricks died in 2017. His widow, Susan, contributed wall text to this exhibition, in which she compared Sloan’s Philadelphia landscapes to those her late husband painted in Jamaica.

“I remember Barkley talking about Lou ‘suiting up’ in his winter protective gear and going out into the harsh elements to paint the winter landscape outside the central Philadelphia environs,” Susan Hendricks wrote. “Sloan was as devoted to the Philadelphia landscape near and around him as Barkley L. Hendricks was to his beloved tropical Jamaica.”

PAFA asked 15 people — including Susan Hendricks, Allan Edmunds of the Brandywine Workshop, and Kelly Lee of the Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy — to write explanatory texts for the exhibition. The multiplicity of voices on the walls, some of which point out the connections between the artists, give “Awakened In You” the feel of a community. The artists in the collection taught each other, collaborated with each other and supported one another.

“It’s impactful we understand Black artistic networks, that they existed,” said co-curator Sarah Spencer. “They were there to elevate one over the other.”

After retiring from the school district in 1993, Clayton became involved with Philadelphia’s cultural sector. In 2000, she became the first chair of Philadelphia Museum of Art’s African American Collections Committee. In that role, she spearheaded a project to highlight PMA’s holdings, which became the 2015 exhibition and catalogue, “Represent: 200 Years of African American Art in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.”

In her preface to that catalogue, Clayton credits her mother, who “introduced me to the arts, encouraging me to study piano, lift my voice in song, and, of course, play with paint and clay and paper.”

She concluded: “It is my sincere hope that the inspiration I received from my mother’s love will be awakened in you, the children of Philadelphia, and all the visitors to the museum.”

The title of this show, ‘Awakened In You,” was pulled out of that preface. Clayton said she chose PAFA to be the recipient of a gift of some of her collection because of its commitment to exhibiting African American art, and the fact that PAFA is also a school.

“There’s a teaching aspect to it,” she said. “I thought that was important for children of all races to see, so they can get an understanding of the ability of people who are like them, or of people who are different from them.”

Clayton also gifted a significant portion of her collection to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York.

But not all of it. Clayton still has art on her walls at home, and still buys when she can.

“I’m not cleaning it out. I plan to continue to buy,” she said. “I buy what I like, and what I can afford. I can’t afford Tanner anymore.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.