J.D. Vance brought Appalachia into the national discourse. PAFA was already there

“Layers of Liberty” launched well before J.D. Vance became the Republican vice presidential candidate, but the exhibit still meets the moment.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Most major museums have artworks that are directly tied to the Appalachian region but do not display them as such, according to Ali Printz, curator of the current exhibition “Layers of Liberty: Philadelphia and the Appalachian Environment” at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

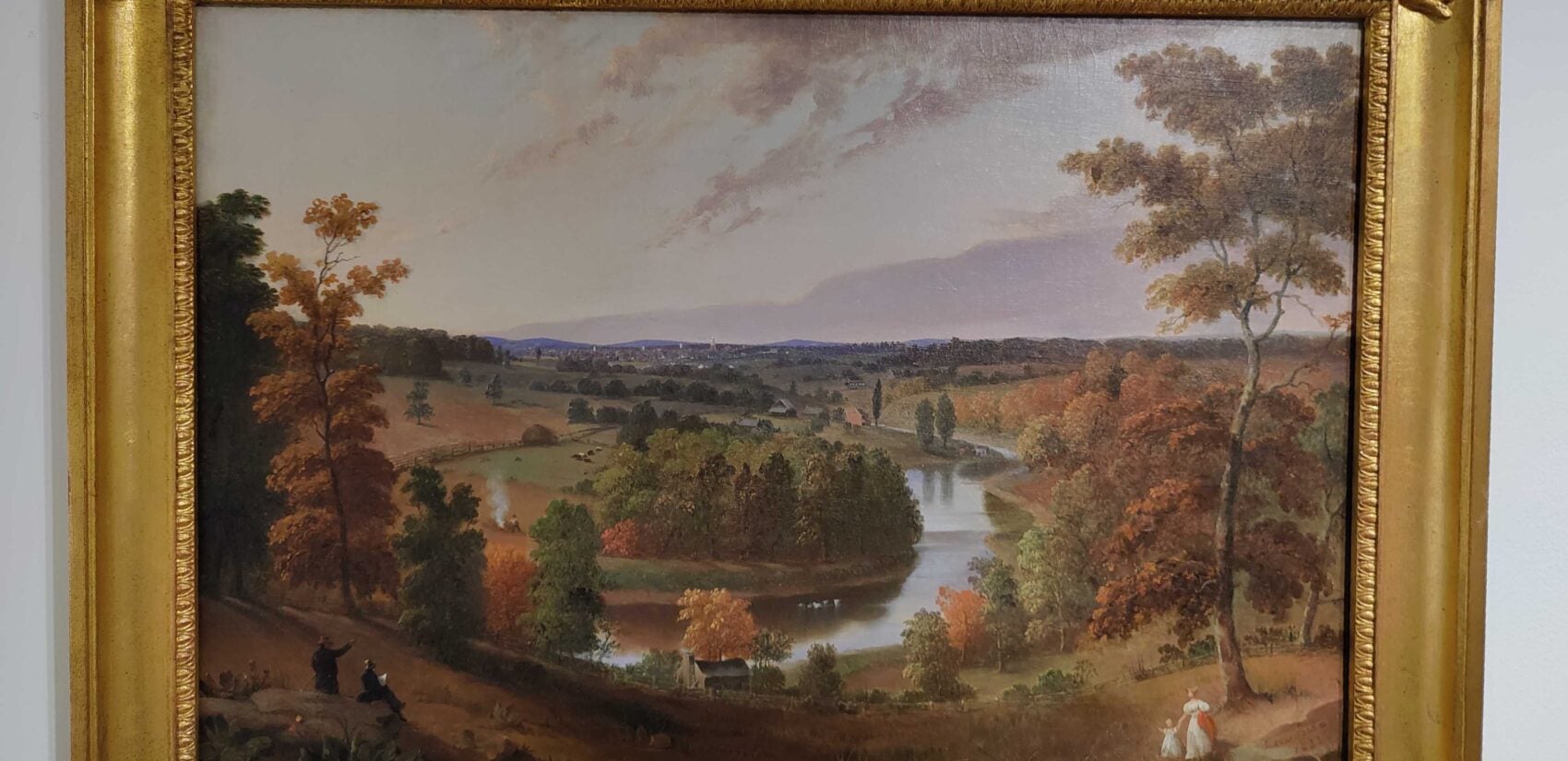

Printz found dozens of paintings and photography in PAFA’s permanent collection related to Appalachia that have never been grouped together before, from the grandiose mountain landscapes of the 19th century Hudson River School to the coal-black abstract brushwork of Franz Kline, an abstract expressionist originally from Wilkes-Barre.

“What I found in my research, and being myself Appalachian growing up in West Virginia, is that the stereotyping of the region is so deeply ingrained, it’s like a systemic thing that has been imprinted in American culture,” she said. “No one is looking at Appalachia, because Appalachia has been edited out of the story.”

“Layers of Liberty” was conceived and opened well before Ohio Sen. J.D. Vance became the vice presidential candidate on the Republican ticket this week. For the moment, he is arguably the nation’s most high-profile Appalachian.

Printz says the author of the bestselling memoir-turned-movie “Hillbilly Elegy” is perpetuating the stereotypes that she is trying to expose in the exhibition. The book, about Vance’s upbringing in a community ravaged by drug addiction and his ambition to rise out of poverty, has been criticized in some places for its demeaning depiction of a broken, working class community.

“He basically used it for his own personal gain and then continued to throw Appalachian people under the bus,” Printz said. “There’s some people that see through it and there’s some people that don’t, but I absolutely think that everything that he’s put forth is vapid.”

The Appalachian Mountains region is a sprawling geological area of more than 200,000 square miles connecting 423 counties across 13 states, including all of Printz’s home state of West Virginia and about 70% of Pennsylvania.

It loomed large in the early years of the republic as the first frontier. Appalachia served as source material for the growing nation, providing timber and coal needed for rapid industrialization, particularly in eastern Pennsylvania and Philadelphia.

“Anthracite coal basically built Philadelphia,” Printz said. “The country was quite literally built on the backs of Appalachian labor and in its biodiversity that ended up fueling the country.”

“Layers of Liberty” attempts to make visual connections between Philadelphia and Appalachia, an extractive relationship that tended to be one-way. Even the early Hudson River painters who were inspired by the nearly spiritual beauty of the landscape painted scenes that avoided mountainsides where clear-cutting had already begun.

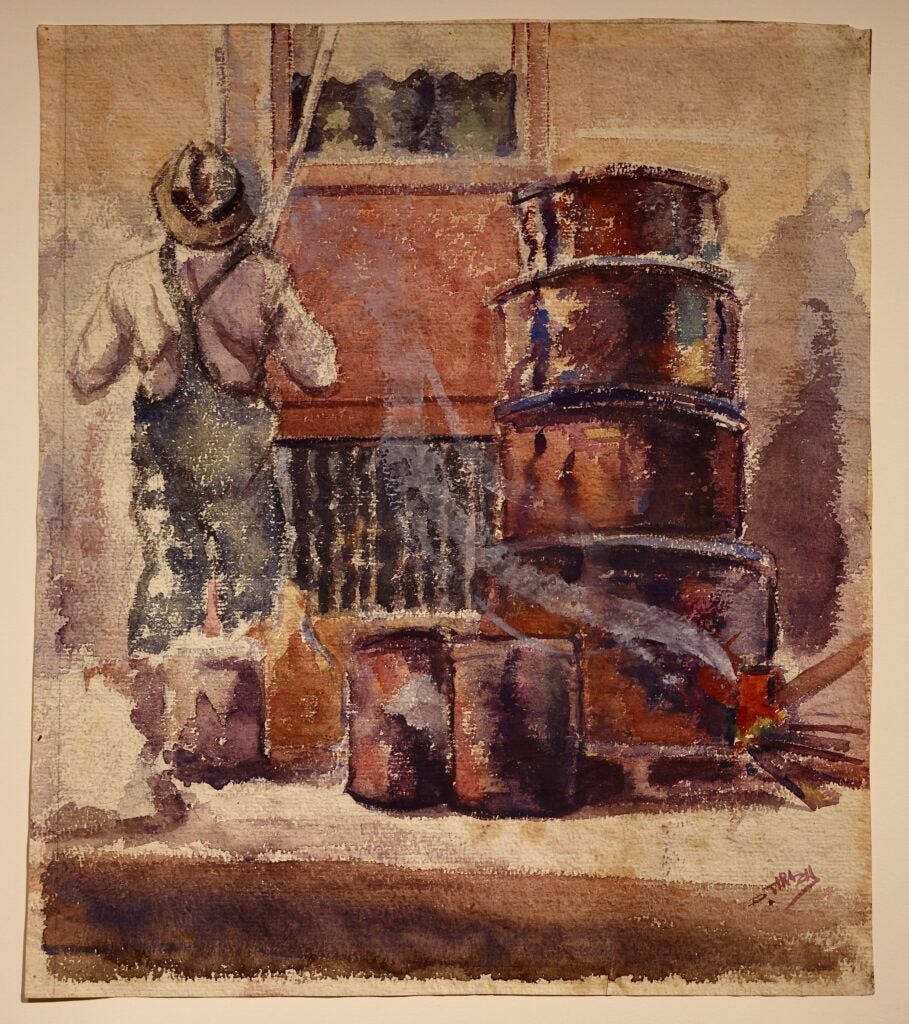

Some works in the exhibition are in awe of the massive feats of engineering undertaken to extract resources from the region, like the watercolors of steel mills, slate quarries, cement works and oil wells by Herbert Pullinger circa 1915. Other artists depict the labor involved, like a gouache of a Black worker stacking oil barrels by Dox Thrash.

Other artists are more explicitly critical of the industrialization of Appalachia. Phillip Evergood’s “Mine Disaster” is a large painting crowded with workers and families exploited by the mining industry.

The sometimes otherworldly beauty of Appalachia has always enchanted artists. Working decades apart, Thomas Pollock Anshutz and Hugh Henry Breckridge both found an expansive palette in the region, painting watery scenes in nearly psychedelic colors.

“It can help us kind of understand America a little bit better because it was the first American frontier,” Printz said. “It’s the elephant in the room that’s always been there and ignored because there’s so many outsider interests and money in Appalachia, in extractions.”

Printz hopes “Layers of Liberty” can begin to correct ingrained perspectives regarding Appalachia, particularly as the region becomes a political talking point in the run-up to the 2024 election.

“If you’re elevating a people and their culture, that prevents outside interests from getting what they want out of the land,” she said. “But if you make them look like they’re dumb and they don’t know what they’re doing and they need to be modernized, that’s the incentive to go in and take what you want.”

“Layers of Liberty: Philadelphia and the Appalachian Environment” will be on view at PAFA until Nov. 3.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.