Pa. town law says landlords can’t rent to ex-drug offenders; one woman fights back

Listen

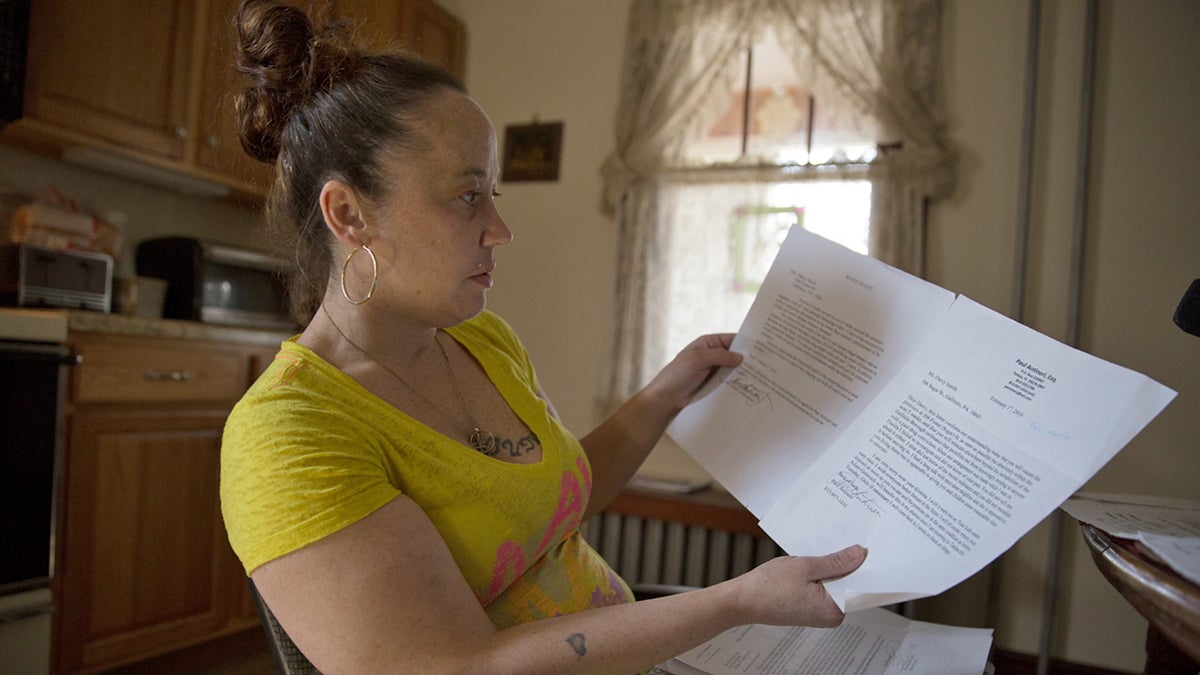

Darcy Smith

In a handful of Pennsylvania communities, it’s illegal for private landlords to rent to people convicted of a felony drug offense within the past seven years.

That could change if one woman’s lawsuit is successful.

Her name is Darcy Smith. She lives in Gallitzin, a 1,600-person borough in Cambria County.

Background

Cambria County’s per capita caseload of paroled ex-drug offenders ranks second out of 67 counties, according to a Keystone Crossroads analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau and state Bureau of Probation and Parole.

The per capita rate of fatal overdoses in the county also ranked second in the most recent report on the subject from the Center for Rural Pennsylvania.

Experts say high-level dealers are attracted to a market with less competition than big cities.

For drug dealers, that means greater profits without risking with turf warfare, plus a new crop of clients and pushers.

Smith is one longtime local who got involved, and is currently under supervision as part of her sentence for a felony drug conviction.

She was one of 44 people — along with her then-boyfriend — arrested during a sweep in 2012.

It wasn’t the first time. Smith’s two-decade rap sheet includes a prior drug dealing conviction in 2001. There’s also trespassing, multiple DUI’s, assault, theft, perjury. She’s upfront about her history, but says she’s finally changed.

“I don’t even wanna go outside my house, let alone go to a party. You know. I’m too old for that crap,” says Smith, 38. “I’m not fightin’ nobody today. My body’s injured. I’m too old for this crap. I’m tired. I’m ready to sit down. I’m ready to just chill out, take care of my kids, my kids are getting older, and they mean everything to me. So I just want to be here for my kids. I’m done. My kids are done being hurt, and I’m done hurting them.”

Smith got out of jail in 2014 and has lived with her three kids in Gallitzin ever since, within a mile of her entire immediate family.

Darcy Smith has been living in Gallitzin with her children and family close by ever since she was released from prison in May 2014. She says she’s done with her past criminal activities and that she wants to keep her children in Gallitzin. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Darcy Smith has been living in Gallitzin with her children and family close by ever since she was released from prison in May 2014. She says she’s done with her past criminal activities and that she wants to keep her children in Gallitzin. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Felon tenant ban

In February, she landed a rent-to-own deal on a house there.

But no sooner had she signed the lease, she got an eviction notice:

“Dear Darcy, this letter confirms your understanding today that you will vacate the premises at 306 Foster/Sugar St. as soon as possible but absolutely within the next two weeks and that you will relocate elsewhere beyond the jurisdiction of the Gallitzin borough ordinance that prohibits me from knowingly renting to anyone with a past drug conviction.”

In January 2016, an ordinance took effect in the borough banning landlords from renting to anyone with a felony drug conviction within the past seven years.

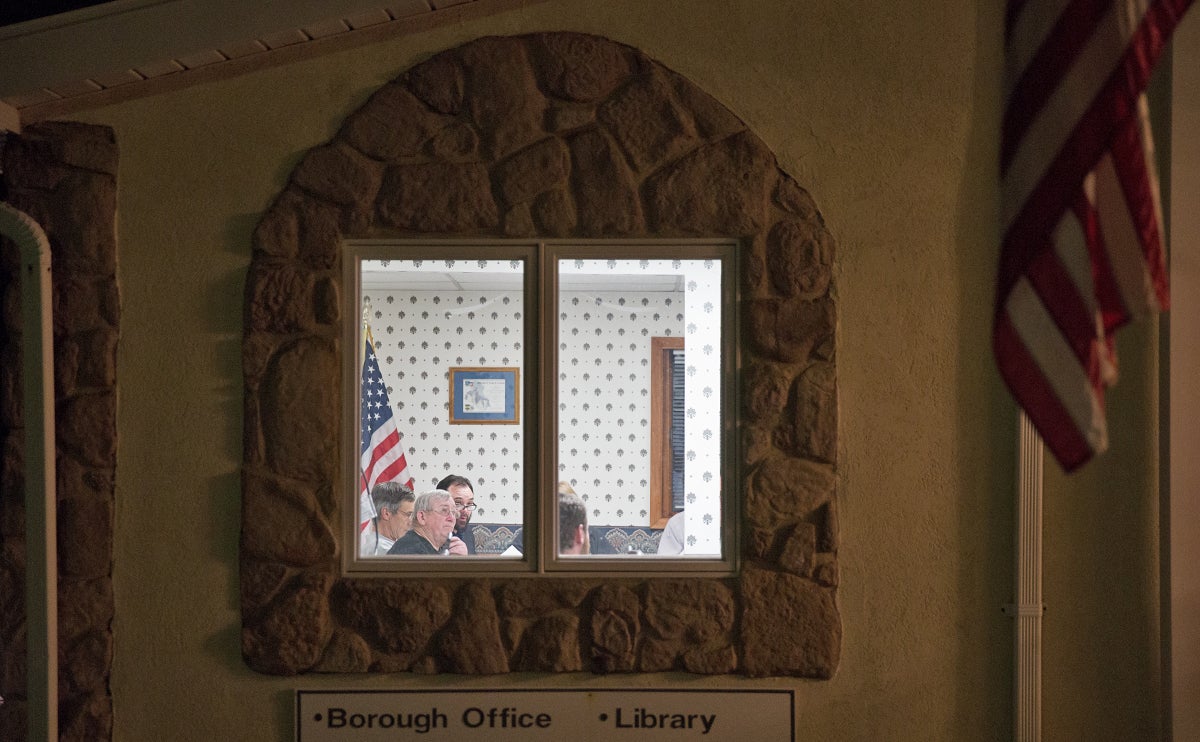

Officials won’t talk about what prompted them to pass the law because, they say, they don’t want to harm the borough’s chances of prevailing in Smith’s lawsuit.

The ordinance itself says its aims is to deal with Gallitzin’s drug problem.

But it’s unclear what else local leaders have tried.

Gallitzin, a small borough with about 1,600 residents, passed an ordinance in January 2016 that bans landlords from renting to anyone who has a felony drug conviction on their record with in the past seven years. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Gallitzin, a small borough with about 1,600 residents, passed an ordinance in January 2016 that bans landlords from renting to anyone who has a felony drug conviction on their record with in the past seven years. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Since 2010, just one arrest in Gallitzin has led to a conviction for felony drug offenses, according to data provided by the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts. Retired corrections officer Bob Bukowski lives in Gallitzin and says he doesn’t agree with the law.

“If the DOC, or Department of Corrections, and our judicial system believes that one of the functions that’s most important is to rehabilitate somebody, then part of that function is them coming out to society and being amongst us, and being amongst their family. And if you try to separate them, where are they gonna go? You might move them into a worse environment,” Bukowski says.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development recently issued guidance warning that it “could be” illegal to turn away ex-offenders in certain cases.

(Although it’s not uncommon for public housing authorities themselves to turn away ex-offenders , depending on the offense, they might have to, according to HUD guidelines).

Even before the announcement earlier this month, the consensus among experts seemed to be that the bans wouldn’t hold up in court.

And that an outright ban like this by local government is unusual.

There haven’t been challenges or moves to repeal ordinances in Sunbury or Mifflinburg, the other Pennsylvania municipalities where we found rules similar to the one in Galltizin.

Smith’s lawyer Tim Burns says he hasn’t found precedent, exactly, but is going to try to use a case, Fross versus Allegheny County, argued by the Pennsylvania ACLU’s Pittsburgh office.

There are differences between Smith’s case and that one, which overturned local restrictions on where sex offenders could live, says Sarah Rose, an ACLU attorney.

Here’s one:

“Gallitzin is saying well, we don’t want convicted drug offenders living anywhere in the borough unless they have enough money to buy a house,” Rose says. “So I think the, kind of, rationale for Gallitzin to do this is a lot less persuasive than Allegheny County, and Allegheny County’s was not very persuasive either.”

Burns describes them as small, “conservative, blue-collar family towns” where local officials are “doing what they think’s best to combat” a “serious drug problem.”

“They’re just going about it the wrong way,” Burns says. “They’re penalizing the wrong people. My client’s someone who’s trying to rehabilitate herself, get back into society and be productive. How’s that going to stop the drug problem in Gallitzin and Cambria County?”

Cambria County has the highest number of supervised ex-offenders per capita in Pennsylvania; for drug offenses, it’s number two, according to our analysis.

Gallitzin Police Chief Jerry Hagen says the borough and surrounding area’s drug problem isn’t unique. But what about its rare law for landlords, which Hagen’s tasked with enforcing? Is it a last resort of some kind? “Can’t really comment on that,” Hagen says.

No one would.

Not the solicitor.

Not past and current council members who voted for the ordinance.

Not Mayor Raymond Osmolinski, Sr. — and it was his idea. Councilwoman Nancy Knee did have a bit more to say.

“I can tell you one thing. There were more positive comments than negative. People came forward and said, praise our mayor for doing it. Because people in town believed there was a need for it,” Knee says.

Most members of the Gallitzin Borough council, Mayor Raymond Osmolinski Sr., and attorney David Consiglio refused to comment or answer questions about the ordinance. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Most members of the Gallitzin Borough council, Mayor Raymond Osmolinski Sr., and attorney David Consiglio refused to comment or answer questions about the ordinance. (Lindsay Lazarski/WHYY)

Smith’s landlord Paul Antinori — the person who wrote the eviction letter — doesn’t agree with the ban.

Antinori says he didn’t ask Smith about her criminal history when she inquired about renting from him. But he says he felt like he had to. He says he can’t afford the $1,000-a-day fine the ban imposes.

“That’s like a double punishment. Not only do they pay their debt to society for their conviction, now they can’t live in the town? That doesn’t make any sense,” Antinori said.

Antinori’s semi-retired to Florida, by the way. He doesn’t live in Gallitzin.

Lifelong resident Sabrina Bukowski, cousin of Bob Bukowski, says she wouldn’t live here either, if she could choose.

She says she’s sick of being confronted by the remnants of drug use.

“That new playground they put over on the other side of town here, over across the bridge. Well, the first year they cleaned it up, do you know what they found? Needles. OK, that’s disgusting. What are kids wearing in the summer? Sandals. Some of them, no shoes,” she says.

Bukowski is a mother and pushing 40.

Like Darcy Smith.

Smith says it’s her kids that keep her in Gallitzin. She says they seem happy at school, and that teachers seem attentive and invested in their education.

“I’m not going to make my kids unhappy just because these people don’t want me to live here,” Smith says.

They’ve been able to stay put for the past couple months because a Cambria County judge barred the borough from enforcing the ordinance pending a court decision.

The case is up Wednesday.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.