Oysters once again on top of the world [photos]

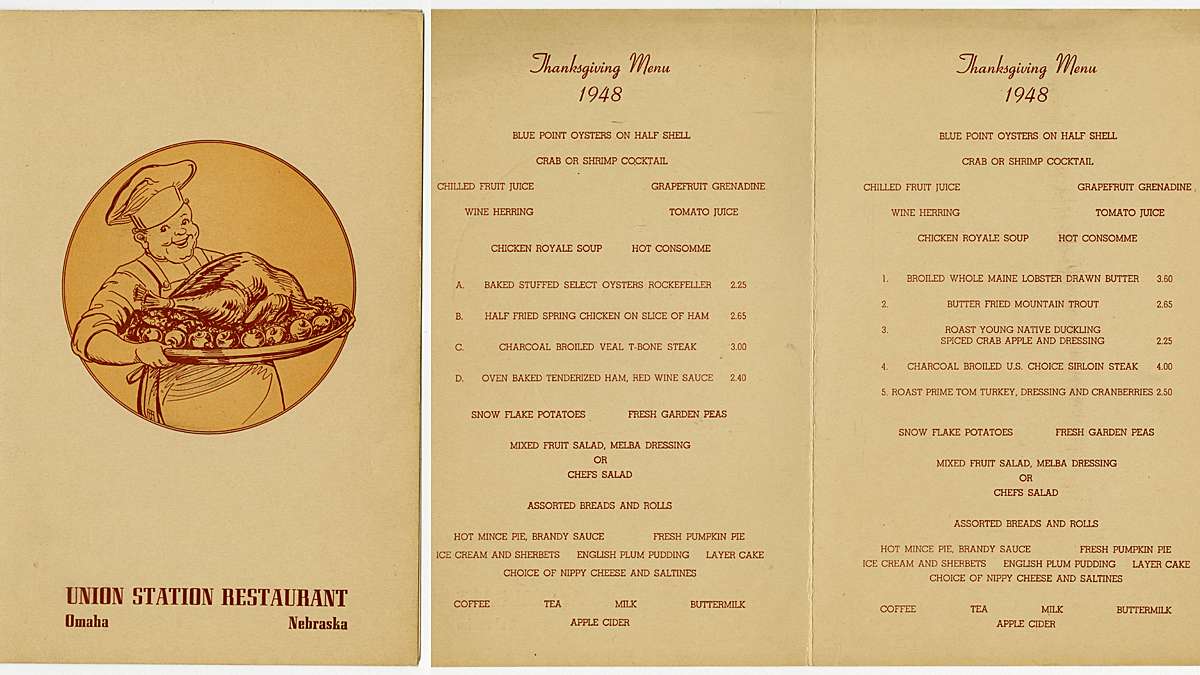

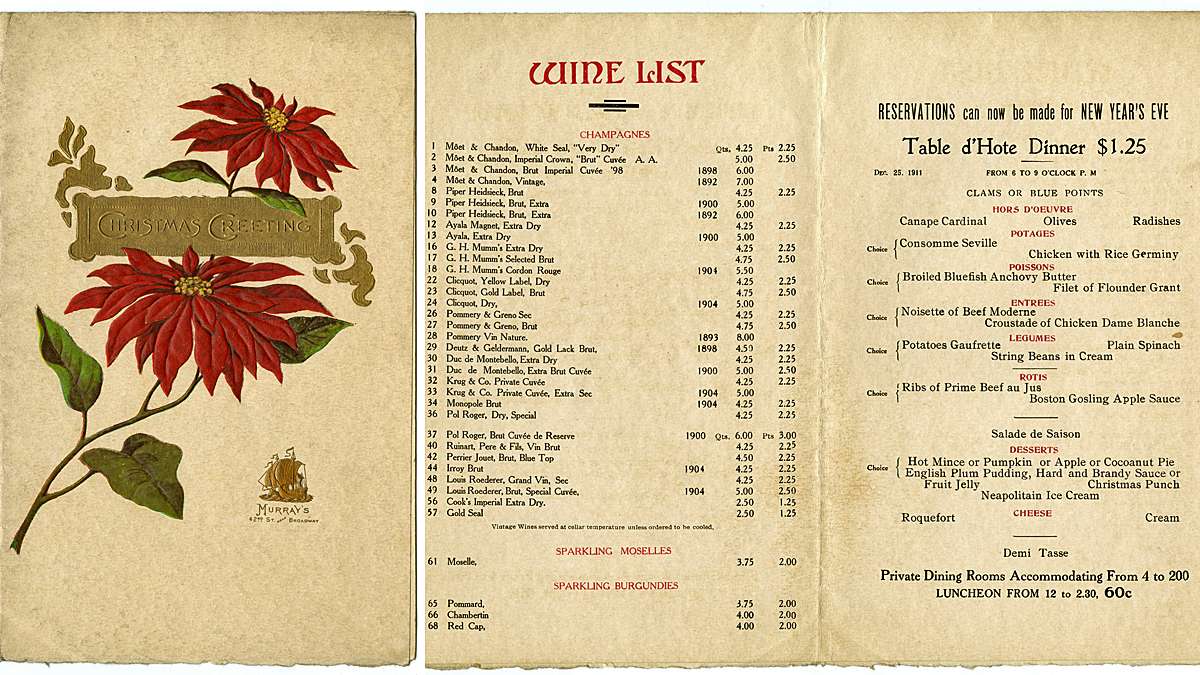

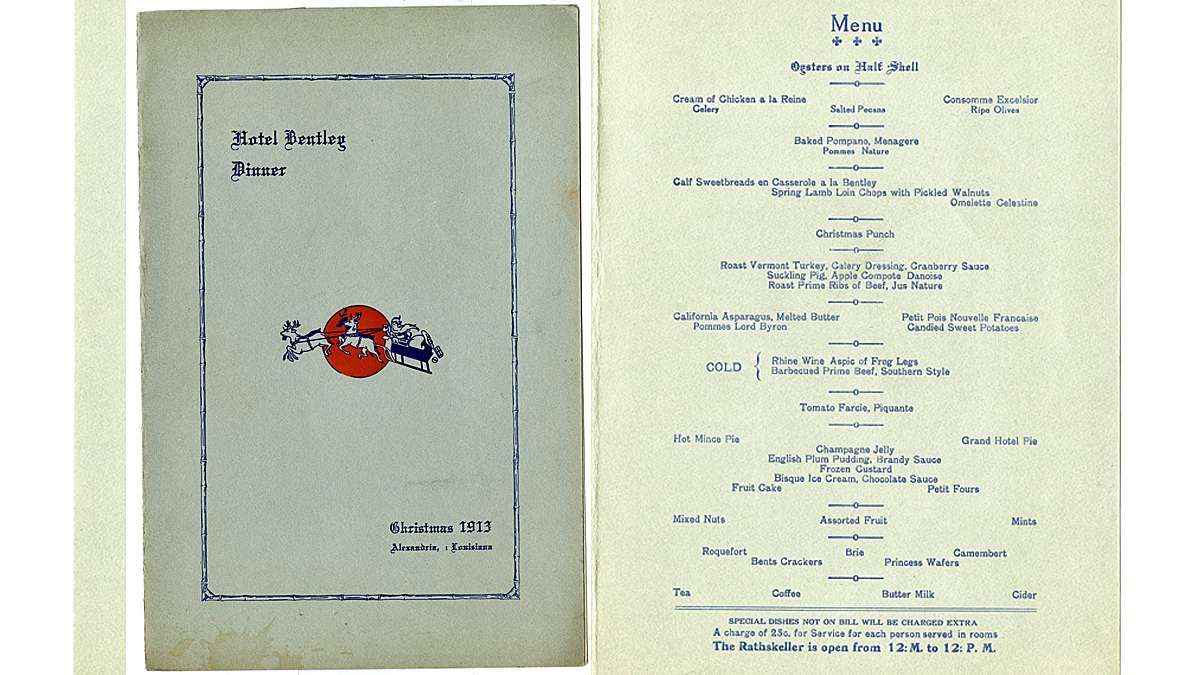

ListenOver the years, one item has consistently appeared on restaurant menus and dinner tables during the holidays. (No, it’s not the turkey.)

It’s the oyster.

And thanks to aquaculture, branding and what experts call consumer confidence, the oyster has seen a resurgence well beyond its humble beginnings.

Aficionados describe them as salty, sweet, silky, firm, clean, strong, and briny. Some have a smooth texture, while others offer a grassy finish. They can be mellow, buttery, icy, or plump.

Just five species of oyster have given the world more than 300 varieties, each boasting its own unique flavor profile, with one for every palate and every pairing.

Oysters have held a place at the table for centuries, around the country and here in the Philadelphia region.

“Well before the Roman Empire, oysters were being pulled from the streams and the bays,” said Kathy Gold, immediate past president of the Philadelphia chapter of Les Dames d’Escoffier International, an invitation-only, philanthropic organization of professional women in food, fine beverage, hospitality and agriculture.

“But as a dish of elegance and celebration, it was more in the Victorian times in this country,” she said. “When it was a sign of wealth to be able to supply and have on your gorgeously laden table something that was so exciting and so expensive.”

From a rarity in households of Victorian privilege, oysters today are as accessible as a trip to your favorite restaurant. Like The Oyster House on Sansom Street, an East Coast-centric oyster bar, where third-generation restaurateur Sam Mink and his family have been keeping tradition alive and shattering a few myths along the way.

A few of the city’s favorites

“We have nine oysters on our list, and maybe one or two Pacific,” Mink said. “Our oysters start in the mid-Atlantic, starting in the Chesapeake, all the way up to New England. We do Long Island, and all the way up to Canada.”

The most popular oyster these days is the Sweet Amalia from Cape May, New Jersey. It’s a delicious, plump and meaty oyster, Mink said.

“Wellfleets from Cape Cod have a strong name behind them, brand recognition,” he said. “They produce a nice meaty, salty oyster.”

Longtime oyster shuckers Cornell Rhodes and Amin Lawrence are well acquainted with both varieties. They’ve been at the Oyster House for 20 years, even before Mink.

“They go through about 1,000 oysters a day, just for happy hour, between 5 and 7. And about 600 of each variety a week. That means they shuck anywhere between 10,000 and 12,000 oysters a week,” said Mink.

That’s a whole lot of shucking going on. And the customers slurp ’em down, all year round.

“Oysters are inherently a celebratory food,” Mink said. “They’re a little bit expensive, so they have a cache of being a special item.”

This time of the year — from late fall through early winter — is prime time for oysters.

“They’ve had all summer and fall to fatten up and eat up before they go dormant in the cold winter,” Mink said. “So they’re really juicy, really plump, full of flavor, and they’re a great food to eat as you celebrate the holidays with friends and family. Especially with a nice glass of sparking wine to go along with it.”

The rule of ‘R’

How about the old rule that you should not eat oysters in a month without an “R”?

“There are a few theories,” Mink said. “One is that there was no refrigeration in the months without an ‘R,’ and they happen to be the summer months, so we’re talking about May, June, July, and August. So if we’re talking about refrigeration, oysters have to stay cold to stay fresh.

“But the true story behind the ‘R’ months was it was actually a preservation technique started by our founding fathers in the Colonial days,” he continued. “Oysters spawn in the summer time. So in order to rejuvenate the oyster beds, they needed to let the oysters spawn to produce more oysters.”

In the Delaware Bay, home of Sweet Amalias and Cape May Salts, wild oyster populations are back on the rise.

Depletion, then a resurgence

“Oysters were of great commercial importance in Delaware Bay, and ecologically they’re one of the foundational species,” said Danielle Kreger, science director at the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, a national nonprofit program that works to protect and restore resources.

“Oyster reefs were reported by the early settlers as covering much of the bay,” said Kreger, who’s also part of Drexel University research faculty. “We still have some of that in Delaware Bay, even better than in Chesapeake and neighboring watersheds. We’re doing better than our neighbors.

“But it’s still a very altered ecology. And part of the reason for that is thought to be the loss of much of that oyster stock.”

Current oyster populations in the Delaware Bay are only a small fraction of their historical size.

“Nevertheless, they are still robust, and support a sustainable oyster fishery,” she said. “Fishermen remove 2 or 3 percent of the biomass or the population of oysters per year, leaving most of them behind to produce baby oysters.”

The multimillion-dollar fishery in the Delaware Bay consists primarily of wild stock, she said.

During the 1950s and the 1970s, diseases wiped out much of the native oyster population — particularly in warmer and saltier area. And with climate change, the water is growing warmer and saltier.

The good news is oysters are gradually building up resistance. And while populations have been in decline, baby oysters in a hatchery can be selected according to their disease tolerance and farmed in more controlled conditions, Kreger said.

This aquaculture is responsible for the resurgence and growth of the oyster populations along the East Coast.

“There’s a lot of good quality waters in the Delaware Bay and suitable habitat to have aquaculture, but nevertheless, we trail the rest of the United States and the rest of the world in terms of aquaculture development,” she said.

Despite some obstacles, Kreger said, the industry holds room for growth. She said the future is “pretty bright” for aquaculture of oysters in the Delaware Bay and the surrounding area.

“In terms of sanitation, the states of New Jersey and Delaware have some of the most robust monitoring programs for water quality in the whole nation, and so people who ask for Delaware Bay oysters should take heart that they’re getting a good product,” she added. “So long as it comes through the normal seafood supplier chains.”

Robust regulations strengthen consumer confidence

One of the region’s largest suppliers is Samuels Seafood Company, a wholesaler based in Philadelphia.

Joe Lasprogata, a marine biologist and vice president of operations, has been working for Samuels for more than 25 years.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection “does a great job regulating the water quality to ensure that the product is safe. Because it’s a ready to eat type of product, it’s important to ensure that it’s safe and wholesome for people to consume.”

Samuels delivers to a customers in a 300-mile radius of the city by truck — from just over the Connecticut border, out through Manhattan, all through New Jersey, down past Washington, D.C., into Northern Virginia, and as far west as Pittsburgh. The company also has an operation in Las Vegas.

On any given day, Samuels sells 20,000 to 25,000 oysters to area restaurants, caterers, hotels and supermarkets. Over a holiday weekend, that number can climb up to 40,000 oysters each day.

“We can access 300 different varieties of oysters,” said Lasprogata. “All these varieties have taken on the characteristics of the environment where they’re grown.”

Samuels sources oysters from as far north as Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island in the Canadian Maritimes, and as far south as the Carolinas.

“We have a tendency to stay away from the warmer water oysters,” Lasprogata said.

Over the years, he has seen a lot of changes in the seafood industry, from the rise of sushi bars to the way chefs order filets instead of the whole fish. The biggest change, he said, has been the evolution of food safety standards, citing the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point regulations enforced by the Food and Drug Administration.

“Food safety aspect has improved with HACCP, which made all the seafood companies, from the producer all the way through, make sure that the food safety standards were improved and traceable, and accountable for,” he said.

“Oysters is a nice success story,” Lasprogata said. “Twenty years ago, there was just oysters. And it was a phenomena that many restaurants had drifted away from. People were not eating raw oysters like they do now. I think that has everything to do with product confidence, and also it has to do with the advent of aquaculture in the U.S.

Back then, consumers would probably be dining on wild oysters, perhaps from the Chesapeake or maybe out of Cape May, he said.

A win-win for ecosystem, diners

In the intervening years, water quality has improved, literally dozens of aquaculture facilities have developed different varieties of oysters along the East Coast, and restaurateur confidence and consumer confidence have increased. Oysters are again at the peak of popularity

“Oysters are a lot like a grape,” Lasprogata said. “They take on the characteristics of the environment in which they grow. They can be a little bit salt. If they’re from a little bit brackish water, they might have a milder flavor..

“It’s kind of a win-win situation,” Lasprogata said. “When you put shellfish, whether it’s clams or oysters back into the waterway, they’re filter feeders, so they actually improve the environment itself. And they only impact the environment in a positive way. And that allows us to have really nice access to the product at a reasonable price.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.