Officials working on opioid crisis in Pa. weigh in on Lycoming County’s Marino, who dropped bid to be Trump’s drug czar

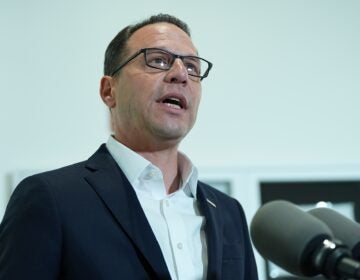

“This was a failure of government," said Pa. Attorney General Josh Shapiro.

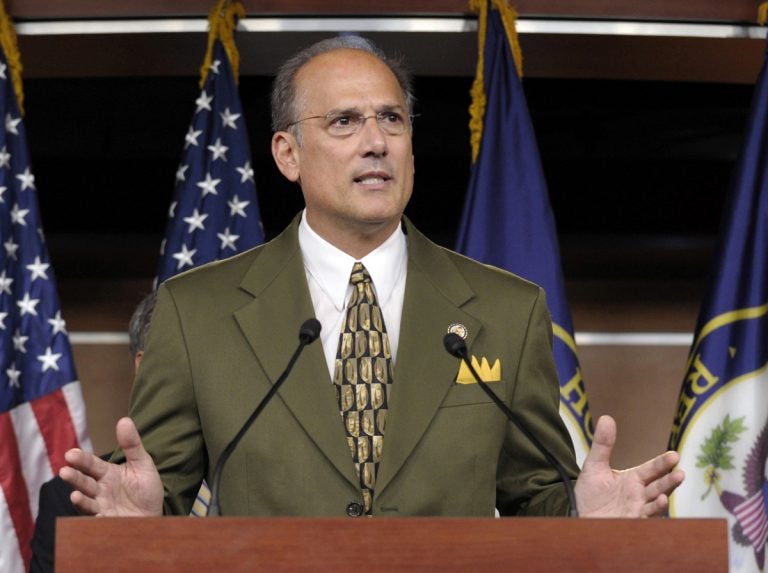

In file photo, Rep. Thomas Marino, R-Pa., speaks during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington. Marino, President Donald Trump's former nominee to be the nation's drug czar, is defending his role in writing a law that critics say weakened the government's authority to stop companies from distributing opioids.(AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)

After a damaging report on the opioid crisis from “60 Minutes” and The Washington Post, Pennsylvania Congressman Tom Marino withdrew his name this week as the next possible drug czar under the Trump Administration.

Whistleblowers and former U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration employees say Marino, a Republican from Lycoming County, lead the way to pass a bill that essentially handcuffed them from doing their job.

Previously, the DEA could slow the rate of opioids into the black market by holding distribution companies accountable for suspicious orders of prescription drugs. But ex-DEA officials say Marino’s bill stopped them and effectively helped fuel the opioid crisis.

The bill sailed through Congress with no objections and was signed into law by President Obama in 2016.

Since the “60 Minutes”/Washington Post report, many lawmakers and Obama administration officials say they didn’t grasp the details of what the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act would do.

Pennsylvania, like many other places in the country has been hit hard by the opioid crisis. In 2016, more than 4,600 people died of drug overdoses in the state — a 37 percent increase from 2015, according to the DEA.

“We are losing 13 Pennsylvanians a day,” says Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro. “And the numbers continue to escalate.”

Shapiro, a Democrat, says he was disgusted by the “60 minutes”/Washington Post report.

“This was a failure of government from the Department of Justice to Congress,” he said. “But make no mistake, it was engineered by the powerful pharmaceutical industry from the very beginning.”

Shapiro along with 40 state prosecutors across the country are targeting opioid manufacturers and distributors in their own multi-pronged investigation that could potentially trigger legal action.

“I hope that President Trump actually puts someone in that position who’s going to be on the side of law enforcement, on the side of actually solving the problem,” said Shapiro, “not in the pocket of the pharmaceutical industry.”

Marino, a former federal prosecutor and Lycoming County District Attorney, did not return a request for comment. In a statement, he defended the new law as one that would help stem the crisis while ensuring that people who really need prescription opioids can get them.

He represents Pennsylvania’s 10th district, which includes 15 counties in the northeastern and central parts of the state.

Within Marino’s district, Lycoming County Coroner Chuck Kiessling sees the consequences of opioid addiction up close.

He was also mentioned in the “60 Minutes”/Washington Post investigation — when a mother recounted the phone call she received from Kiessling that her son had died.

“My heart goes out to these families. This is just horrible,” he said. “I spend many a day and night trying to figure out: what do we do differently?”

But Kiessling is not ready to point fingers at Marino just yet.

He knows Marino, and has discussed the opioid epidemic with the Congressman.

Kiessling acknowledges that drug companies can be a problem and that addiction can start with prescription pills. But since most of the overdose deaths he sees are from heroin, he’s more concerned with getting people recovery help than placing blame on the higher levers of power.

“Unfortunately, there’s people that start in the programs, fall off the wagon and start using again,” he said. “It’s just a vicious cycle until they eventually end up through my office.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.