Nominating petitions: ‘Last bastion of democracy’ or simply a slog?

Listen

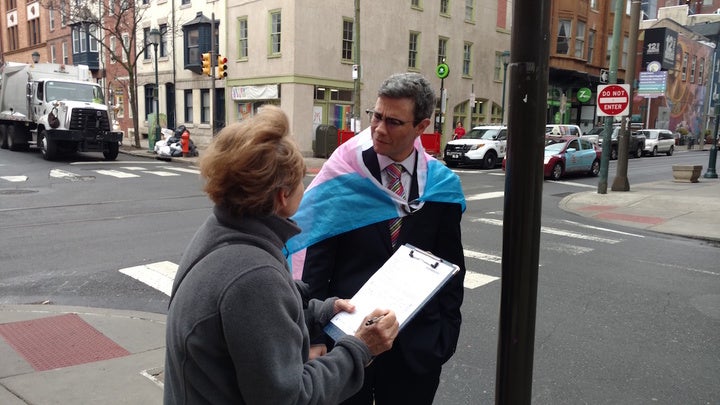

Henry Sias, a Democratic candidate for Common Pleas judge in Philadelphia, gets a passer-by to sign his nominating petition. (Katie Colaneri/WHYY)

If you happen to see someone running for political office, you might consider giving them a hug — or buying them a stiff drink.

Tuesday at 5 p.m. is the deadline to file nominating petitions to get on the primary ballot in Pennsylvania.

It’s the first step of running for office, and it’s the part of the race even veteran politicos dread.

“This is probably the worst part of the job,” said Annie Havey, deputy director of Philadelphia’s Republican Party.

“[It’s] that three weeks that I try and drag myself out of bed every morning,” said Dan Siegel, a Philadelphia-based Democratic political strategist.

Every state has some form of “ballot access” laws. In Pennsylvania, candidates need to collect a certain number of signatures from registered voters in their party and in their district, and pay a nominal fee.

So, if you’re a Republican running for local school board, you need 10 signatures from other registered Republicans in your neighborhood. If you’re a Democrat running for district attorney of Philadelphia, you need 1,000 signatures from registered Democrats across the city.

Sounds straightforward and pretty democratic, right?

“These things don’t sound hard, but there are so many places where it can go wrong,” Siegel said.

To be valid, a signatory must write his or her name, address and signature legibly. The person collecting the signatures also has to sign each page and have it notarized. Some people don’t like to admit they’re not registered to vote and will sign petitions anyway. Sometimes, they fill out the form incorrectly by writing “ditto” marks or writing ZIP codes instead of dates.

If rival candidates think you don’t have enough good signatures, they can file a court petition and get you removed from the ballot. So candidates often collect hundreds or even thousands more signatures than they need to make sure they have the minimum required.

And they have about three weeks during the final throes of winter to do it.

If you’re a Republican in predominantly Democratic Philadelphia, your job is even tougher.

“Looking down a block and seeing one Republican on that list and there’s 100 houses and then, you have to walk miles and miles and miles or drive to the next Republican … and pray to God that they’re actually in the house when you knock on that door,” Havey said. “And your fingers are bleeding from the wind cracking your skin — I kid you not. You’re freezing your butt off.”

‘Physically exhausting’

So, I wanted to see for myself just what it’s like.

Henry Sias is a Democrat running to be the first out transgender Common Pleas judge in Philadelphia. He agreed to let me tag along with him last week as he stood outside a Planned Parenthood in the city’s Gayborhood collecting petition signatures, the blue, white and pink transgender flag draped around his shoulders as a cape.

He needs 1,000 signatures and, at this point, he was in good shape with about 1,600.

Sias has never run for office before, but had no illusions that this would be easy. Still, he admitted he was drained.

“This has been physically exhausting,” he said. “But I love talking to people about the courts … and getting people engaged in thinking about how it can be made better and what they want to see in the courts. That’s been very interesting.”

Standing there in the rain on an unseasonably warm morning, waiting for people to pass by, it was easy to see why it’s a slog.

Sias hears “no” a lot.

In fact, the first six people all waved him off, including two men who replied with an emphatic “NOPE” when he asked if they were registered Democrats in Philadelphia. A woman pushing a baby carriage down the street said she was from New Jersey; then another woman rushing by said she didn’t have time.

It took about five minutes before he got his first signature, which doesn’t sound terrible until you consider that, at that rate, he would get only about 12 signatures in an hour — and then, it would take more than 83 hours, or about three and a half days, to get 1,000. Fortunately, Sias has had help from his wife and some of his friends.

If you’re thinking, “Yeah, but running for office shouldn’t be easy since actually being in office is hard,” no one I spoke to for this story disagrees.

In fact, filing nomination petitions is widely considered to be the first test of just how strong and organized a campaign is as measured by the number of extra signatures collected, as well as the ranks of staffers and volunteers hitting the streets.

Adam Bonin, a veteran election lawyer in Philadelphia, points out the courts have made the process a bit easier over the years. For example, in 2012 the state Supreme Court ruled that signatures could be valid even if the person used his or her nickname — such as Katie for Katherine — so long as it was clearly a diminutive of the full, legal name.

“If you put in the work, you can get on the ballot,” Bonin said. “It’s not an unreasonable burden.”

But the stakes can be high.

Just in the last few years, several candidates in Pennsylvania have been booted from the ballot for having invalid signatures.

Babette Josephs was state representative for the 182nd District in Philadelphia for 28 years, until she lost her seat to Brian Sims in 2012. She was fighting to get it back two years later when a judge found she didn’t have the 300 signatures required.

One man she hired to circulate petitions listed his own address wrong, so the 171 signatures he collected were thrown out, putting her under the minimum.

Josephs admits it was her fault. She was visiting family out of state and thought she’d left the job in good hands.

“You have to be there to supervise, I knew that,” she said. “I thought I could pull it all off, but I couldn’t, so that’s that.”

‘The last bastion of democracy?’

Josephs still thinks getting on the ballot should require some legwork.

In higher-stakes races, that means money for a good field operation and for lawyers to defend you if your opponent challenges your petitions.

So is this just another example of how the political system is “rigged” in favor of people with money and power?

Siegel says proving how much support a candidate has on the ground is a “beautiful thing” — he even calls it “the last bastion of democracy” — but thinks the law could be tweaked to give candidates more time to complete the process, for example.

“And I think that there needs to be a higher standard for challenges because it’s just so easy to file a challenge that people do it and see if they get lucky,” he said. “I think if these things change, this process would be more representative of the democracy it’s trying to protect.”

And while the warmer-than-usual weather did make the process a bit easier this year, remember this is just the beginning.

The weeklong challenge period starts Wednesday.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.