No, Stu, Open Streets aren’t the enemy

Welcome to what sadly is becoming a regular Eyes on the Street feature: The [sic] Byko Files.

What are The [sic] Byko Files? Well, “[sic]” comes from sic erat scriptum, Latin for “thus it was written,” and is usually inserted in a quote to indicate when the original speaker—not the subsequent writer—made some sort of mistake; and “Byko” refers to that curmudgeon-in-chief at the Philadelphia Daily News, Stu Bykofsky, who has made a career out of swapping stodgy facts for dodgy opinions. And “Files” just has a nice ring to it.

The papal weekend was a real headache for a lot of Philadelphians. Street closures, truncated public transit services, and security fences all made getting through large parts of Center City more complicated and a lot slower than normal.

But there was a silver lining to this dark security cloud (not to mention a golden halo around the reason for all of it). Away from the high-security Francis Festival Grounds, car-free streets within the security perimeter were open for everyone else to enjoy.

When cities suspend automobile traffic for no particular purpose – like a festival – it’s called Open Streets.

The Open Streets concept inspired Stu Bykofsky’s error-riddled rant last week: A 3-point checklist is needed before ‘Open Streets’ (never mind that it isn’t clear at all what this tripartite test is; we’re not here to critique Byko’s writing, only his tenuous relationship with facts and logic).

Byko correctly notes that Open Streets could be accurately described as “Closed Streets – to cars.” But then he says that this is “Orwellian Newspeak.”

Accusations of Orwellian machinations simply because someone branded something you dislike positively has been a tired cliché since 1984, if not longer, so perhaps it’s no surprise that Stu forgets that Newspeak wasn’t merely spin, but rather government’s attempt to control thought through speech.

It’s a nuanced point, but Byko isn’t one for nuance. So, I shouldn’t have been surprised by the broad, sweeping generalizations with which he answered his opening question: “Who owns city streets?”

(Stu was asking philosophically, but if you’re interested in a surprisingly complicated technical answer, here you go.)

Stu says cars. “A city is defined as much by cars (including buses and delivery trucks) as by tall buildings, dense population, noise and street lighting, each of which some people don’t like.”

Of course, city life was once also defined by cholera and typhoid, deadly byproducts of a tainted water supply. Rather than taking that as a given, Philadelphia built the Fairmount waterworks, and a modern sewage treatment system.

Besides relative density, cities aren’t defined by a set immutable qualities. Cities change. In fact, in order to stay relevant, vibrant and growing, cities must change. But Stu isn’t a fan of change: “Pedestrians no more belong in the street than cars belong on the sidewalk. This understanding has been around forever.”

The implication is clear: Cars own the streets today, they owned the streets before, and they shall own the streets forever. Streets are not a place fit for man, beast, or non-motorized machine.

Despite his advanced age, Stu hasn’t been around forever. Neither have cars. Automobiles first began to appear on Philadelphia streets during the fin de siècle. According to “Philadelphia: A 300 Year History,” the first “horseless pleasure carriages” were allowed into Fairmount Park in 1899 on the proviso that they did not frighten actual horses. In 1905, there were fewer than 500 registered cars in the city. But by 1918, that number exploded to over 100,000.

Of course, Stu didn’t literally mean forever – but his argument boils down to this: cars owning the road is the way things are, and, therefore, the way things should be.

According to Stu, support of Open Streets means you have a “mental disorder”. He also calls “neo-luddites in love with the 18th century,” (even though bicycles weren’t even invented until the 19th century) and a handful of other insults.

Stu simply does not like cyclists. His hatred is so strong that nearly anything associated with a bicycle becomes tainted in Stu’s mind. Such is the fate of Open Streets: infected by having the support of cyclists, this proposal—far more focused on a pleasant walking experience than anything to do with bikes—becomes the inspiration for not one, but two columns (so far) marshaling unsubstantiated assertions to support his irrational biases.*

When he isn’t dealing in historical inaccuracies and personal attacks, Byko is busy blowing down straw man arguments. He writes: “You don’t have to delve deeply to discover the anti-car lunatic fringe that rhapsodizes about a city without cars.”

Let’s be clear: No one has proposed a city without cars. No one thinks that should, or even could, happen.**

Rather, a loose mix of individuals, many of whom don’t even own bicycles, are proposing to temporarily shut down a few blocks from vehicular traffic on a few weekends without the same intense density of programming that usually accompanies Philadelphia’s many street festivals.

Byko points out that lots of businesses did poorly during Philly’s experiment with Open Streets, i.e. the papal visit. Of course, the evidence he trots out in support of that statement is suspect, to say the least. But even if Alan Butkovitz’s statistically insignificant, misleading survey of companies within the papal security apparatus was representative of how Philly businesses did that weekend, it doesn’t demonstrate of how Open Streets would affect local stores.

In Los Angeles, businesses along roads closed to automobile traffic during CicLAvia events saw sales improve between 25 and 66 percent. Other road closures, such as South Street’s Blocktoberfest or the Food Trusts’ Night Markets, often mark the local busiest day of the year for nearby businesses. And with SEPTA running and road detours clearly marked, they don’t cause insurmountable traffic snarls.

Similarly, there are dozens of studies now showing how better bicycle infrastructure results in sizeable economic gains. While stores may lose a few spots dedicated to cars or see less automobile traffic in front of their stores, they gain cyclists. And because bike infrastructure acts to calm traffic and make streets feel safer to pedestrians, stores also gain more foot traffic.

And with the exception of places selling big items like furniture, businesses are better off replacing cars with bikes and pedestrians. It’s difficult to drive past a store, notice a window display, decide to park, find parking, and then go shop. Slower moving bicycles are more likely to see something, and even without good bike parking, finding a street sign usually isn’t that hard. And it’s even more obvious for pedestrians.

Now, this doesn’t work everywhere – you need places that can support foot and bike traffic. But most of Philadelphia is densely populated enough.

This isn’t to say we should permanently ban cars, or remove all parking. It’s about balance. In order to maximize revenues for the retailers and restaurants located in Center City and the surrounding, densely populated neighborhoods, Philadelphia needs more bike lanes and bike parking.

According to the Mayor’s Office of Transportation & Utilities, a standard bike lane costs $39,000 per mile to paint. A buffered bike lane, like those on Pine and Spruce, is $49,000. For comparison’s sake, resurfacing a road costs about $236,000 per mile.

Paint is relatively cheap. So, too, is the police overtime for temporary road closures.

In terms of direct costs, the stakes are low. But in terms of Philadelphia’s identity and future, it’s incredibly high.

Marginally shifting the street balance from cars towards bicycles would produce dramatically large economic gains for local retailers. It’s what economists call a Kaldor-Hicks improvement.

Temporary street closures of a few downtown blocks would be a Kaldor-Hicks improvement, too. Most businesses would benefit. And so would our health: air pollution dropped dramatically over the papal weekend. The health benefits of less pollution and more exercise concomitant with fewer cars and more cyclists and pedestrians shouldn’t be underestimated.

Nor should the traffic safety improvements be discounted. The same day Stu’s story ran last week, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia celebrated a birthday of sorts: the Pine and Spruce Street buffered bike lanes turned six years old.

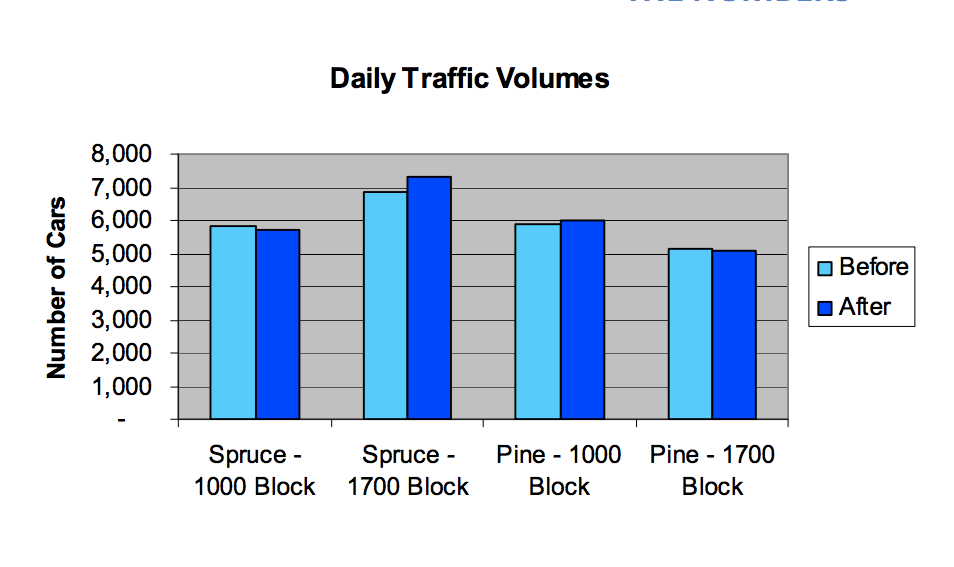

Both streets became significantly safer after the bike lanes were installed. Not just for bicycles, but for cars and pedestrians: in the first year, there was a 44 percent reduction in serious car crashes, and a 58 percent reduction in pedestrian crashes. Across all transportation modes, the number of crashes is down nearly a quarter. Perhaps most notably, those drops aren’t because drivers now avoid the streets. In fact, daily traffic volumes barely changed and even went up.

Ultimately, Stu says, the people should decide whether they want Open Streets or not. Specifically, he says City Council, “as the representative of the neighborhoods” should have the power.

When you live in the Birthplace of American Democracy, it can be tough to argue against such populist appeals. Yet, some urbanists do. They would prefer if decisions about Open Streets, bike lanes and the like were left up to the experts who work at the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities, the City Planning Commission, Streets Department, PennDOT and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission.

That’s who – after frequent and repeated rounds of community outreach for feedback – makes most decisions about the layout and utilization of Philadelphia’s roadways.

It’s no wonder that Byko wants Council to decide, and the urbanists want the technocrats.

During Mayor Nutter’s time in office, City Council has been decidedly more conservative–in the philosophical sense–than the administration, and especially so on transportation-related issues.

You’ll be hard pressed to find a political scientist or constitutional scholar who thinks Philadelphia’s system of ten council district fiefdoms makes sense. Stu wants to make it worse, letting his anti-cyclist ends justify the means.

*This isn’t meant as an attack. We all have irrational biases. In fact, many behavioral psychologists believe that humans almost always come to our conclusions first based off of gut feeling, and then use logic and reasoning afterwards to construct an ex post facto justification for our impulse.

**Someone, somewhere, might think this is a good idea, that we should ban cars permanently from the city. That hypothetical person is wrong. And characterizing a group’s position by the most extreme member is an inductive fallacy.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.