Beach body: Cape May shows off its scrapbook of a historically Black beach

The Carroll Gallery at the Emlen Physick estate displays family photos of Grant Street Beach, the city’s once-segregated beach.

Listen 1:36

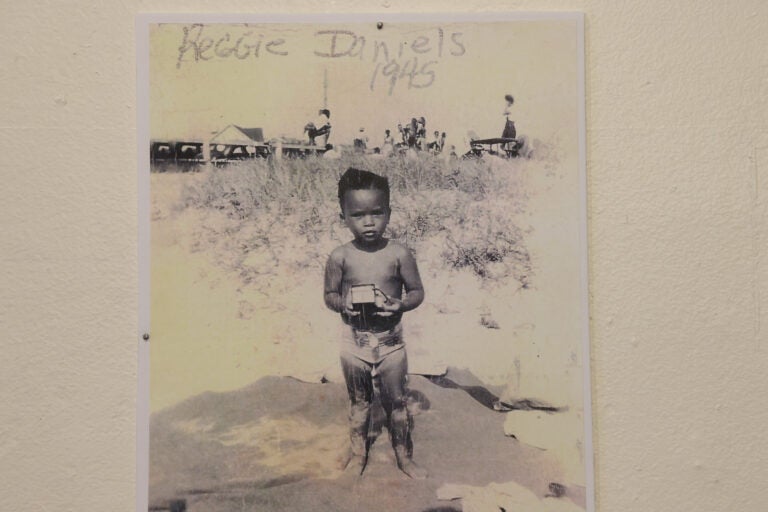

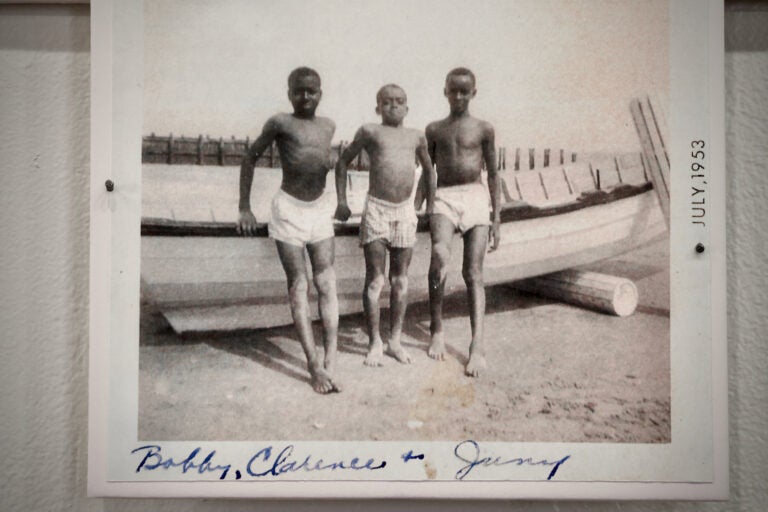

In a photo from 1953, boys puff out their chests for the photographer on Grant Street Beach. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

“I was a beach kid. Couldn’t wait to head to the beach. Always in the water,” said artist Chanelle René, born in West Cape May and who frequently visited relatives while growing up in the 1980s.

“My mom would take me, or one of my uncles, but my question was: Why do we go to this beach?” she said. “My mom answered, ‘This is where we go.’”

René’s mother grew up on Grant Street Beach in Cape May. So did her grandmother. In the early 20th century, this beach was segregated, designated exclusively for Black people, the policy imposed such that its racial identity remained entrenched for generations.

“We could go to any beach we wanted to in Cape May at that time, but if I was taken to the beach, more times than not my mom would see an old classmate, a family friend, or other family members who you knew,” she said. “You were gonna bump into people that you know.”

Since 2022 René has been painting historic scenes of Grant Street Beach, some based on archival photos from the 1930s and 40s, others based on her own imagination. The artist revels in eye-popping color, putting her figures against abstract pink backgrounds and dressing them in classic 1940s bathing suits with bold colors that did not exist at the time.

Even the ice cream cones, eaten while sitting on the boardwalk, sparkle with colorful jimmies.

Her paintings accompany photos of New Jersey’s historically Black beaches in the exhibition “Line in the Sand: Segregated Beaches in Cape May and Atlantic City,” now on view at the Emlen Physick Estate in Cape May. The display focuses on two beaches circa 1930s through 1960s: Grant Street Beach in Cape May and Chicken Bone Beach in Atlantic City.

Chicken Bone Beach, aka Missouri Avenue Beach, is the more well-known of the two. During its heyday it was visited by famous Black entertainers who came to perform in Atlantic City Nightclubs: Sammy Davis, Jr., Louis Jordan, the Mills Brothers and showgirls from the nearby Club Harlem were known to spend time on the beach.

The activities at Chicken Bone Beach were documented by a professional photographer at the time, John Mosley, whose images of Black life in Philadelphia are held at the Charles Blockson Library at Temple University. For the last 50 years, the Chicken Bone Beach Historical Foundation has been protecting and promoting the historic legacy of the beach, mostly through jazz performances.

On the other hand, Grant Street Beach has led a much quieter life. Few if any celebrities are known to have visited, and no professional photographers are known to have chronicled the beach. The photos on view in “Line in the Sand” are candid snapshots entirely sourced from local family scrapbooks, collected by the Center for Community Arts (CCA) in Cape May.

“It wasn’t even that much known by us until we started doing this research almost 30 years ago,” said Hope Gaines, of CCA’s historical committee and curator of “Line in the Sand.”

In the 1990s, the CCA started conducting oral histories with longtime Black residents of Cape May to document the community’s history. Those interviews ultimately were published in 2022 as the book “Black Voices of Cape May: A Feeling of Community.”

“We started interviewing people and after a couple of years people started giving us stuff. They kept handing us things,” Gaines said. “Everybody has these pictures of their kids digging holes in the sand, or lined up like this.”

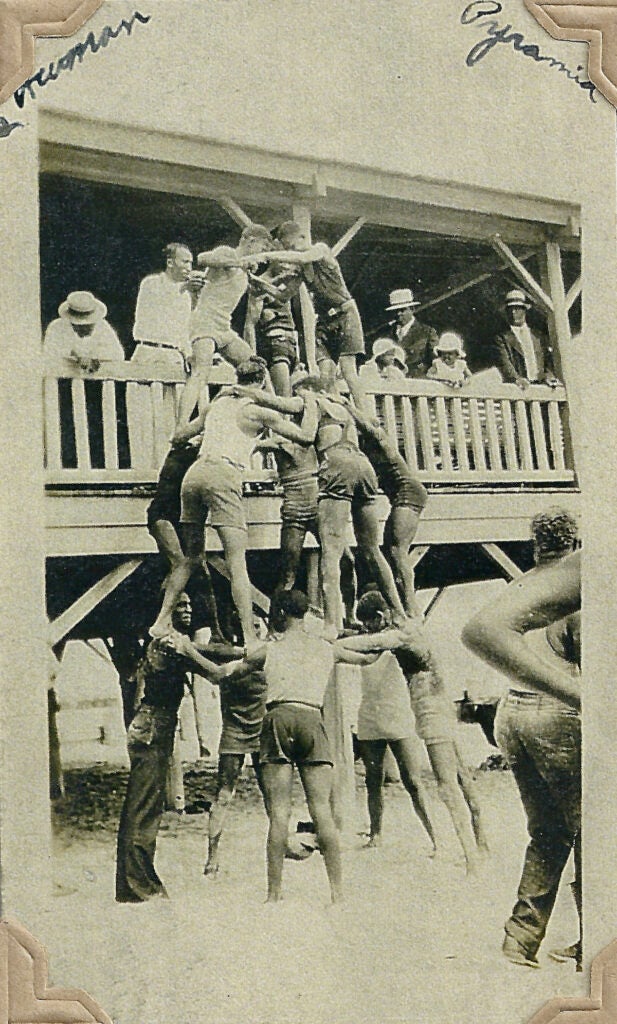

Gaines pointed to a photo of a group of Black men on the beach standing on each other’s shoulders, forming a pyramid. Nearby is a panoramic series of shots showing a line of Black lifeguards posing on the sand. A trio of women posed with their arms around each other’s shoulders, circa 1940s. They were waitresses at a nearby hotel who spent their afternoons at the beach between the lunch and dinner rushes: one has an insouciant expression, another seems shy.

The photos are peppered with quotations from residents explaining how the Grant Street Beach worked. Unlike Chicken Bone Beach up the shore, where powerful hotels were able to enforce segregation so Black people could not visit their beachfronts, Grant Street Beach was never formally segregated. However, residents knew where they would be welcome, and where they likely would not.

Black beachgoers were typically guided by Black lifeguards who would be assigned to certain beaches, typically Grant Street and Windsor Street. These beaches were located away from more prominent whites-only hotels. At Grant Street sat a pavilion with snacks and bathrooms, operated by a Black proprietor.

“We weren’t forbidden, there was no sign, but it was just automatic that we went there,” remembered Lois Smith, a jazz singer, in an oral history interview. “If you happened to go to another part of the beach, nobody, as I can remember, ever said anything. But you were made to feel uncomfortable by your own: ‘What are you doing down there? We’re all up here.’”

All of the family photographs from Grant Street Beach have been digitally scanned and printed. There are no originals on display. Many of the people seen in the pictures are identified in the wall text, and sometimes on the photo itself: one picture of a shirtless man showing off his beach physique has the word “Daddy” roughly scrawled into the image. He is Dr. E. W. Shervington.

(Emma Lee/WHYY

Some people could not be identified and Gaines has been relying on visitors to the Emlen-Physick estate’s Carroll Gallery to make the connection. One picture of a young girl sitting in the sand with a bucket and trowel has been recently identified as Carol Shervington, the future Miss Grant Street Beach who went on to become Miss Cape May Beach Patrol in 1967.

“I have to confess that we had no idea there was a Miss Grant Street Beach until someone told us about this,” Gaines said. “Now we have a whole new research project that we can work on.”

The exhibition’s wall text describes the sometimes dark history of a racialized beach, for example in 1976 the Cape May Beach Patrol congratulated itself on 47 years without a drowning, forgetting or omitting the drowning death of a Black man named Eldridge Johnson.

Visually, the show is pure pleasure: literally a day at the beach.

“One of our favorites is the lifeguard pyramid that we’ve used in other places. That is everybody’s favorite picture,” Gaines said. “It’s a bunch of guys on the beach who decided to build a human pyramid. Because, what do you do on the beach? A bunch of guys get together and they play.”

“Line in the Sand: Segregated Beaches in Cape May and Atlantic City” will be on view at the Carroll Gallery on the Emlen-Physick historic estate until March 26. The estate is now open for weekend-only winter hours, including President’s Day, Monday, Feb. 19. Beginning March 1, it will be open daily.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.