Is there more than one way to escape a rip current?

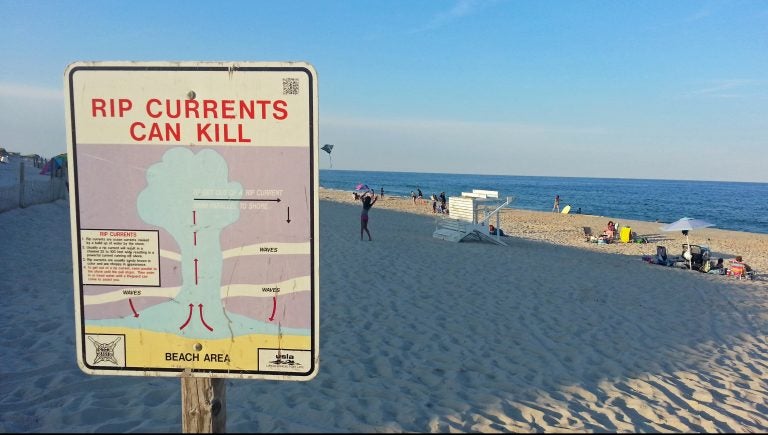

A sign in Cape May instructs swimmers caught in a rip current to swim parallel to the beach to escape. (Alan Tu/WHYY)

(Editor’s note: A previous version of this story cut off the beginning of this story)

If you get caught in a rip current, swim parallel to the beach. It’s a mantra longtime shore visitors are familiar with, as much a part of our summer lexicon as “one scoop or two?” and “pass the sunscreen.”

But, some experts are saying, this well-trodden rule should come with a very important caveat that few people are talking about. Absent this disclaimer, the parallel swimming platitude may be doing more harm than good.

The United States Lifesaving Association estimates rip currents are the culprit in 80 percent of beach rescues, and 100 people a year drown in them. In other words, the thought of encountering a shark might make your heart skip a beat, but you’re nearly 200 times more likely to die in one of these strong slipstreams than in the jaws of, well, Jaws. So far this year, 36 rip current fatalities have occurred across the country, including that of a 24-year-old woman in the Central Jersey town of Long Beach.

With stakes this high, any new science is hotly contested, but one thing is certain – when it comes to long-held ideas about staying safe in the water, there’s been a tidal shift.

What’s a rip?

To swimmers, rip currents are a hard-to-spot nuisance that can put a scary damper on an otherwise idyllic beach day. To oceanographers, they are the strong, narrow flows of liquid energy that sweep out to sea, sometimes as far as 100 yards.

Rips can form along any coastline, and for a variety of reasons. A jetty that interrupts the flow of water can cause a rip. A sandbar that interrupts wave action can cause a rip, hence one of the reasons beach erosion is so problematic. Breaking waves that crash close to the beach, pooling excess water by the shoreline so that it must find a way back out, can cause a rip. Tides, winds, storms and the lunar cycle can all add fuel to the fire or, in this case, water to the channel.

Many people think a rip current pulls a person underwater, but it actually pulls a swimmer away from the coast – sometimes at a rate as fast as eight feet per second. Since people don’t usually find themselves in trouble until they’re already waist-deep, they often panic, and start fighting against the flow of water – which is a lot like trying to ski uphill. Too frequently, they drown when they exhaust themselves.

Historically, lifesaving officials have advocated the parallel swimming approach, encouraging people to exit the rip current as soon as possible. For nearly a century, it’s been a core tenet of Jersey Shore beach canon.

The new science

Ten years ago, Jamie MacMahan, Oceanographer with the Navy Postgraduate School in California, allowed himself to be caught in a Monterey Beach rip current. When he started swimming parallel to shore, as beachgoers are taught to do, nothing happened. Resistance was too great. Feeder currents were working against him.

While feeders get a lot less air time than the rip currents they help form, they can be just as dangerous for the unsuspecting swimmer, and far more stealthy. That’s because they do exactly as their name suggests — they flow parallel to the shore, and feed the rip channel, making it difficult to get the heck out.

You can think of them as the nefarious sidekick – Dr Evil’s Mr Bigglesworth, or Captain Hook’s Smee. But, like all evil sidekicks, feeder currents have their handicap – they mostly feed the neck of a rip channel, or the area in the surf zone. Beyond that, they’re power is diminished.

This knowledge, coupled with a study led by MacMahan in 2010 – a study which is just now entering mainstream American conversation — has led to a new theory about how to beat a rip.

“For the first time, instead of using fixed instruments to interpret the flow field, we used very simple drifters developed by MacMahan,” said Tim Stanton, study co-author. “Essentially, these drifters were short PVC pipes attached to self-logging GPS units that could move with the water. What Jamie found is that the dominant motion of a rip current isn’t just an offshore jet, shooting out to sea like a river. The fluid also veers around either side of the channel to form a series of loops.”

In other words, if you try swimming parallel to the shore as soon as you get caught in a rip, a feeder can push you right back into the rip channel, creating a vicious cycle. Enter the bodily exhaustion lifesaving officials want you to avoid.

However, if you remain calm, and let the rip current sweep you out to sea just a little bit before you start swimming parallel, these loops can actually help sweep you away from the rip channel and back to shore. On a Jersey beach, where the width of the surf zone is smaller than on a west coast beach, the sweet spot where it becomes okay to start swimming parallel is typically near the breaker line.

While the theory has informed the way beach patrols in other countries, like Australia, are educating the public, America’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has so far refused to incorporate the research into their teachings. Their online slideshow encourages swimmers in a rip channel to head left or right, no going-with-the-flow mentioned. This is likely down to the fact that the practice can be scary and, Stanton admits, dangerous, as waves will be breaking over you.

Many Jersey Shore lifesaving officials are wary of the advice.

“I know about the new research,” said Rob Connor, Captain of the Seaside Heights Beach Patrol, which executes approximately 300 rescues a year, 80 percent due to rip currents. “It is possible for a rip to sweep around in this way and carry someone back to shore, but in my 30 years here, I’ve only seen this happen a couple of times.”

Geoff Rife, Lieutenant of the Cape May Beach Patrol, which rescues approximately 700 people a season but hasn’t had a drowning in their 105-year history, reports the same. “The rip currents in Cape May don’t move in a circular motion,” he said. “They sweep literally directly off the beach.” Ben Swan, Lieutenant with the Cape May Point patrol, says: “I wouldn’t recommend floating, because you just don’t know how far it will take you.”

In North Wildwood, where nine people were pulled from rip channels on July 25 alone, Beach Patrol Chief Tony Cavalier points to a sign at every beach entrance that reminds people to swim parallel. “I haven’t read about another theory yet,” he said.

When he was eight years old, Erich Wolf, Lieutenant with the Avalon Beach Patrol, was able to break free from a rip current by immediately swimming parallel to the beach on 18th Street. Letting himself be carried out until the rip died out may also have worked, he said, but it’s difficult to know, since all of these channels are different. A couple of years ago, Wolf received news of a kid and the man who tried to rescue him caught in a rip off of 77th Street after hours. When the guards reached him, the swimmers were 200 yards from shore.

For Stanton, swimming parallel and calmly floating are not mutually exclusive pieces of advice. “It’s been very controversial, but I don’t see this as a controversial thing,” he said. “You can use both of these things to break free from a rip channel. I find it odd that some people want to pick sides in a bullish, macho way. There are cases this information wouldn’t apply — at big pocket beaches, with large headlands on either side, where large erosive events can occur, for instance. But at open beaches like those along the Jersey Shore, the increase of information can be incredibly important.”

The Consensus

When it comes to rip currents, there are several points all experts can agree on: Only swim at protected beaches and, if you do get caught, stay calm, never swim against the flow of water, and try signaling someone on shore who can call 9-11.

But most importantly, try not getting caught at all. In other words, identification is key. Rip currents can be especially calm sections of the ocean, or especially rough patches that some guards refer to as “washing machines.” In either case, the water should be slightly discolored due to turbulence turning up sediment. The channels can be as narrow as 10 feet, or as wide as 100 feet. If you’re unsure, check with a lifeguard.

“Our strategy is preventative,” said Cavalier of the North Wildwood Patrol. “We have to be proactive, or people will drown.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.