Native flora and fauna in the spotlight at the New Jersey State Museum’s ‘Ecosystems at Risk’

The exhibition highlights the state’s natural habitats and efforts to protect them.

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

On average, more than 1,200 people squeeze into every square mile in New Jersey, making it America’s most densely populated state.

One might think the state’s built environment leaves little room for populations of natural flora and fauna.

“Populations are smaller than they have been historically, but a lot of animals are still thriving,” said Dana Ehret, curator of natural history at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton.

“They’re still there,” he said. “We’re gonna do what we can to help them survive.”

Ehret put together “Ecosystems at Risk: Threatened and Endangered in New Jersey,” an exhibition showing the species that call New Jersey home and mankind’s efforts to maintain them.

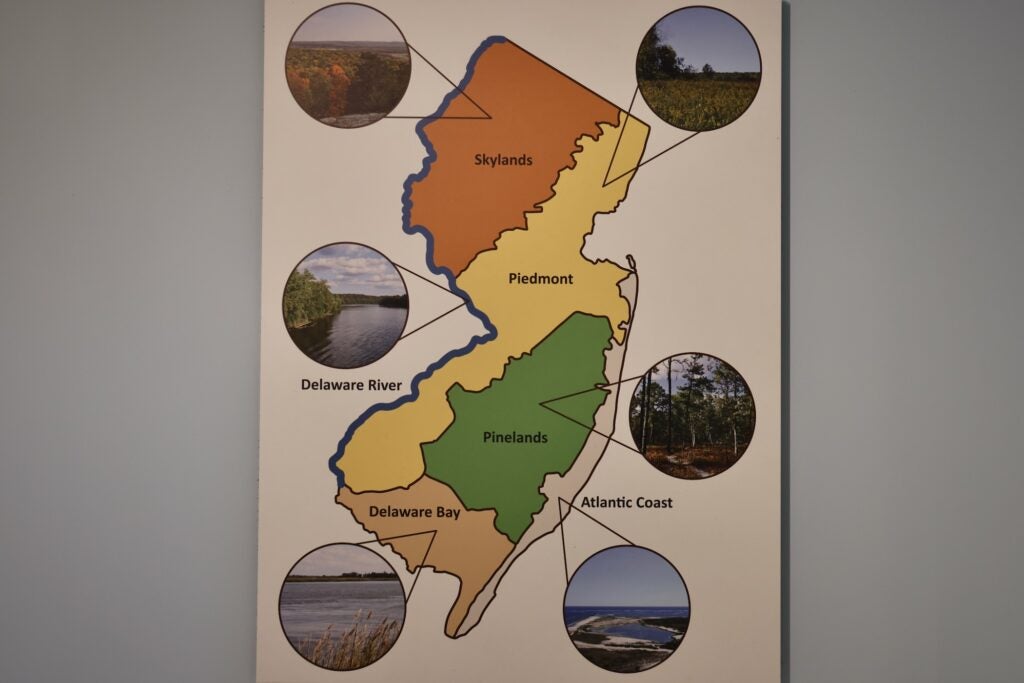

The exhibition breaks the state into five distinct regions, such as the Piedmont, a stretch of terrain from New York to Philadelphia dominated by the concrete ribbon of I-95. To Ehret’s eyes, this area is dominated by low foothills, open grasslands and boggy wetlands.

“The Piedmont is coming down off the Appalachian Mountains. We’re getting into more open prairie-like habitats,” he said. “We have rivers and streams running throughout that area. Lots of open spaces, lots of natural plant habitat for a lot of nesting birds and snakes and other reptiles.”

Giving birds a home

There’s a fight for survival in the Piedmont. The native kestrel, a type of small falcon, has been in a fight for its life for centuries, not just because of people and their cars.

“The European starling is one of the most common birds in New Jersey. There’s flocks of them all over the place,” Ehret said. “They’re actually pretty birds, but they are not native to North America. One of the species that they’ve out-competed very well is the kestrel. They take over nesting areas in the hollows of trees where kestrels would normally nest.”

It’s an avian housing issue. Starlings are able to snap up all the nesting real estate in New Jersey’s hollowed-out trees before the kestrels are able to nest, making it difficult for them to lay eggs and reproduce.

The population of native kestrels had been plummeting for many decades. It is now listed as a “threatened” species in New Jersey. In 2006, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection teamed up with several conservation groups to build and install kestrel boxes throughout the Piedmont region, providing alternative nesting opportunities for kestrels.

Since then, the population of kestrels has rebounded in the state. Observers in Cape May County have counted more kestrels than they have seen since the 1970s, and hatchlings in human-made boxes have increased year over year since 2019.

“A lot of times New Jersey gets a bad rap, but there is an amazing diversity of plants and animals in our state,” Ehret said. “Sometimes we get too buried in our iPhones and iPads to notice the natural world around us.”

Helping animals cross the road

“Ecosystems at Risk” identifies most of northern New Jersey as Skylands, abutting the Appalachian range where bobcats roam. Bobcats need to travel dozens of miles a night to hunt, through a territory that can expand to hundreds of square miles.

But state highways can make roaming difficult, sometimes impossible. I-95, for example, effectively bisects the state, preventing bobcat movement from North to Central Jersey.

To help animals traverse the state, the N.J. Department of Environmental Protection began identifying bridges and culverts that allow wildlife passage underneath roadways.

Connecting Habitat Across New Jersey, or CHANJ, began about six years ago to encourage state agencies, developers and residents to maintain existing passages and incorporate additional passageways into new construction.

“The concern is obvious in a state like New Jersey,” said Gretchen Fowles, a NJDEP biologist who works on the CHANJ project. “It’s so urbanized and with so many roads, wildlife really need to be able to move and get from place to place.”

The efforts of CHANJ recently got a boost from Trenton, where in July legislators passed the Wildlife Corridor Action Plan, which mandates the identification and protection of animal passageways through the state’s built environments.

CHANJ has created a public-facing data map pinpointing built passageways across the state, overlayed with known wildlife routes and areas of protected land.

One of the most prominent passages is in the Pinelands of South Jersey, the largest contiguous forested region in the Eastern United States. But its 1.1 million acres are cut in two by the Atlantic City Expressway, effectively acting as a kind of Berlin Wall for animals in the Pine Barrens.

Near the Frank Farley rest stop, midway between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, is a culvert that allows animals to cross under the traffic corridor. CHANJ worked with the South Jersey Transportation Authority, which maintains the highway, to retrofit the culvert with dry shelf trails helping animals traverse, and erect fencing on either side of the expressway to funnel animals toward the opening.

Motion sensor cameras have been installed inside the culvert to track what kind of animals use it and how often. A CHANJ video monitor inside the Farley rest stop gives motorists a peek at the wildlife below.

“There’s well over 20 different species. Even birds nest in those structures. From coyotes and deer down to very small mammals,” Fowles said. “Skinks and snakes and spiders and a whole gamut of wildlife are making use of those shelves to safely get through the highway.”

Protecting species with fire

“Ecosystems at Risk” at the state museum features a photo of a forest fire that’s been blown up to the size of a wall. The life-size flames appear threatening but the exhibition stresses the importance of fire to the health of the Pinelands. Periodic burnings are crucial for the sustainability of the ecosystem.

Ehret points to native species of plants and animals that have adapted to fire. Certain kinds of pinecones, for example, need to be scorched to release their seeds.

“We have a box turtle shell that was burned in a fire and the animal survived,” he said, holding up a partially melted turtle shell. “This animal would burrow into the sand of the pines, the fire would pass over its shell, and then once the fire’s gone it would come right back out.”

Some fires do more than just scorch, wiping out whole sections of forest. Robert Somes says that is crucial, too. The zoologist with Fish and Wildlife is looking out for the tiny frosted elfin butterfly, a threatened species which thrives in open, savannah-like environments of low shrubs and grasses.

That kind of succession environment occurs after a major disturbance, such as a fire, as a forest builds itself back. In the past, before aggressive fire prevention, the Pinelands burned a lot, creating more open spaces without tree canopies preferred by species like the frosted elfin butterfly.

Somes said the butterfly now seeks out places where the forest canopy has been disturbed by human industry.

“Once fire left, over the last 100 years, the butterflies became restricted to the only disturbed habitats that were kept open: utility right of ways, gravel pits, railroad corridors, airports,” he said.

Somes was walking through Lizard Tail Swamp in the bottom of South Jersey near Cape May, where he has been planting Baptisia tinctoria, or wild indigo, in abandoned gravel pits and utility pole right of ways. Wild indigo grows well in open, sun-dappled places and is the preferred meal of the frosted elfin butterfly.

The disturbances to the landscape are not limited to maintaining clearance for utility poles. Trails that have been cut by off-road recreational vehicles, which Somes said tear up the terrain to the benefit of nothing.

Somes and the NJDEP are currently working on a 20-acre parcel of protected land near Lizard Tail Swamp to sustain a progression of periodic clearings, so there is always a portion of forest in every phase of successive growth.

“The poor butterflies are hanging on here because, well, this is the best thing we got going on,” Somes said. “So, we’ll make do.”

“Ecosystems at Risk: Threatened and Endangered in New Jersey” will be on view until March 15, 2026. On September 20 the New Jersey State Museum will host a free open house from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., featuring tours of the exhibition by curator Dr. Dana Ehret, and representatives from various state environmental agencies with hands-on activities, including NJ Forest Fire Service, NJ Forest Service, NJ DEP’s Fish & Wildlife, NJ School of Conservation, Wildlife Society: NJ Chapter and the Wetlands Institute.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.