New Barnes exhibit is a reflection of Barnes — the collection and the collector

Visitors to the galleries of the Barnes Foundation are often so engrossed in the complicated arrangement of the masterpieces on the walls, they fail to look at the floor.

The parquet flooring is inlaid with dark lines around sculpture and furniture, lines visitors are not allowed to cross. Gallery guards spend much of their time pointing out the lines to people whose eyes are busy looking up.

In her reaction to the Barnes collection, artist Judy Pfaff used every surface of the special rotating art gallery on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia – the walls, ceiling, and floors – to create a psychedelic garden of manipulated photography, foam resin, and metalwork. The floor pieces are bounded by zigzagging metal rails at varying heights. They are impossible to overlook.

The Barnes Foundation commissioned Pfaff and two other artists – Mark Dion and Fred Wilson – to create installations after the renowned collection of modernist work and the eccentric way Dr. Albert Barnes arranged it. Each of the artists in “The Order of Things” turned over unlikely rocks in the Barnes legacy to inform their work.

Pfaff’s piece, “Scene I: The Garden. Enter Mrs. Barnes,” is an homage to Dr. Barnes’ wife, Laura, who designed the arboretum surrounding the original galleries in Lower Merion — a lush, sophisticated garden many visitors overlooked in favor of the paintings inside.

“I really try to grow gardens,” said Pfaff. “I’m bad at it.” The only organic thing in her sprawling, walk-through installation is the process by which she made it. Pfaff tinkered and refined the pieces onsite, reacting to the light and the space. Her metal canopies mimic the gallery arches Henri Matisse painted for Dr. Barnes — amorphous sculptures of foam resin ooze across the floor, and white chandeliers suspended from the ceiling are a tangle of metal twigs and electric candles.

She did, however, bring in a real log she found in a forest; to the horror of the Barnes’ staff, it was still a home to a population of bugs.

Pfaff’s neighbor in the gallery is her polar opposite. Mark Dion created a rigidly formal arrangement of natural science tools against a wall. He chose a particular niche of the gallery because it has very defined borders and edges.

‘The Incomplete Naturalist’

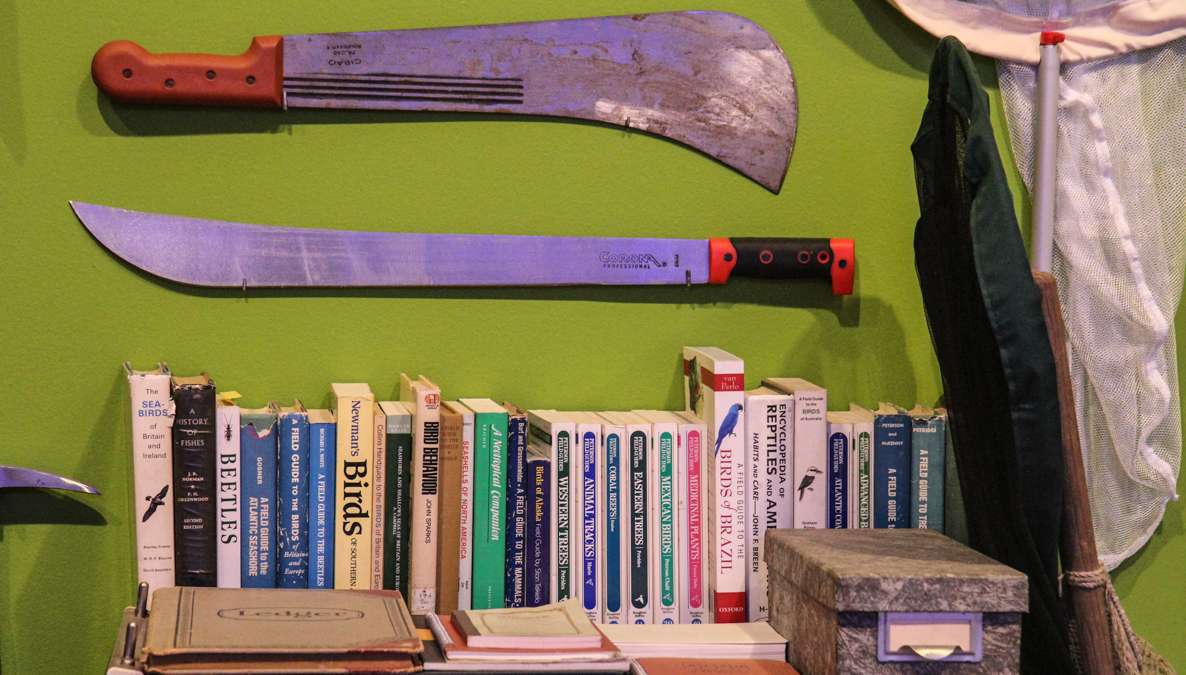

“I’ve known Judy’s work for a very long time, and one of the interesting things about it is you never know where it begins and where it ends,” said Dion. His piece, “The Incomplete Naturalist,” mimics the symmetrical approach of Dr. Barnes, but instead of art, Dion used traps, nets, guns, and storage cabinets a natural historian might use in the field to gather specimens.

It reflects the more “sinister” side of collecting — the act of removing birds, bugs, or art from their native contexts.

“I think every artist has to feel a little compromised by how their work can be used to illustrate someone else’s philosophy,” said Dion. “Everyone who makes things wants them to be seen in their integrity and not to merely be a pawn in someone else’s argument.”

The Barnes Foundation – to its credit – not only did not shrink from Dion’s critique, but encouraged it. The artist is often commissioned by cultural institutions to do an artistic “interventions” where he examines the operation and makes work in response.

“But, do they really want that?” said Dion. “That gets tested when you give a little pushback and try to be critical of them. Soon, you find they are not interested in this kind of interrogation. But the Barnes has been incredibly good about this.”

Instead of the dour yellowish beige burlap Dr. Barnes chose for the walls of his gallery, Dion displayed his field tools against a bright green, to give a “glass half-full” feeling. It’s a very un-Barnesian hue, “apple martini.”

‘Trace’

“The Order of Things” amounted to a test of the foundation’s flexibility to accommodate artists. It bent over backward to fulfill artist Fed Wilson’s requests for his “Trace” installation, in which he re-created “to an 1/8 inch” the administrative offices of the Barnes gallery in Lower Merion.

Whatever art Dr. Barnes could not fit, or did not want in the main gallery, he put in the office. He also stuffed his country estate, Ker-Feal, with paintings and artifacts from his collection. Neither place has ever been open to the public.

Wilson called “Trace” a “ready-made” installation, after Duchamp’s mass-produced objects he presented as art objects. The layers of juxtaposition, irony, profundity, and banality are heightened through re-contextualization. The arrangements of mostly bland office furniture alongside artistic masterpieces speak to the different ways art is perceived by the museum industry versus the public.

Wilson’s work created countless unexpected revelations, most prominently Joan Taylor, the receptionist at the Barnes Foundation in Lower Merion whose desk and swivel chair is used as the centerpiece for “Trace.” The desk and the Cezanne painting that lived above it were moved into the gallery, along with Taylor’s desk nameplate.

Taylor, a former elementary school teacher from Flourtown, died in February while Wilson was preparing this installation. She was 77.

“The Order of Things” will be on view until August 3.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.