N.J. has weak system of state support for black and Latino college students, report shows

Higher education in N.J. is hobbled by inequities that leave many minority students ill-equipped for college and the job market, authors contend.

Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie addresses a gathering Thursday at Burlington County College in Pemberton. Christie is backing away from the use of Common Core school standards, saying the system isn't working for students in New Jersey. (Mel Evans/AP)

Higher education in New Jersey is hobbled by inequities that leave many minority students ill-equipped for college and the job market, authors contend.

Higher education in New Jersey is failing its black and Latino students, according to a new report. And, if that inequity is not addressed soon, the state’s economy will suffer, the authors say.

The report, from progressive think tank and advocacy organization Education Reform Now (ERN) is titled “Locked Out of the Future: How New Jersey’s Higher Education System Serves Students Inequitably and Why It Matters.” In a deep dive into the state’s higher education system, it found harmful gaps between the way the state serves its white students versus its black and Latino students.

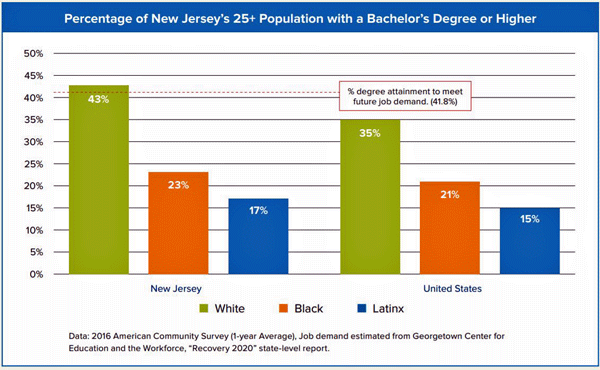

The report shows that a black student in New Jersey is nearly 30 percent less likely to enroll in an in-state public four-year college than his or her white peer while a Latino student is 18 percent less likely. What’s more, those students are also less likely to attain the necessary degrees the workforce demands. According to the report, New Jersey’s white population earns bachelor’s degrees at a rate needed to keep up with job demand (43 percent), whereas black and Latino degree attainment rates (23 percent and 17 percent respectively) lag far behind.

These gaps, the authors say, effectively funnel minority groups away from economic achievement. Moreover, the college affordability solutions presented by Gov. Phil Murphy and other state leaders may not be enough to address these issues.

“We need to expand the way we think about college affordability,” Michael Dannenberg, director of Strategic Initiatives for Policy at ERN, one of the co-authors of the report, said. “When we talk about college costs, typically we only talk about tuition and fees but we aren’t looking at total costs for families and state taxpayers and we aren’t looking at the return on investment for everyone.”

Economic Consequences

The failures of New Jersey’s higher education system will not only harm students, Dannenberg said, but will have ripple effects throughout the economy for generations. Students who don’t feel they can afford or succeed in New Jersey classrooms are opting to earn their degrees out of state. The report says approximately 43 percent of recent high school graduates leave the state to attend college elsewhere and those who leave are less likely to return.

Meanwhile, minority students in New Jersey aren’t being equipped to fill the state’s job needs. The report states that New Jersey ranks third among all states and the District of Columbia in its need for college-educated workers. But the significant degree gap between white students and their black and Latino peers is blocking students of color from contributing to New Jersey’s economic future.

New Jersey’s education system works to “lock out” students from disadvantaged backgrounds, according to the report. Its data show racial stratification in who gets to attend two- and four-year schools, an inefficient and inequitable way of distributing state funding to these schools, an “unjustifiable” degree gap between white and minority students, and a university system that fails to prepare black and Latino students effectively for the business and workforce demands of the economy.

New Jersey’s k-12 public school system continues to be one of the most segregatedin the country, putting black and Latino students in a tougher position to start applying for colleges. The report notes that in reading assessments, black and Latino students are less than half as likely as their white peers to score as “proficient” or “advanced” at the end of high school. In math assessments, black students are barely one-quarter as likely, and Latino students are much less than half as likely as their white peers to score highly.

On top of academic issues, the “sticker shock” of many in-state schools can scare lower-income students away from even applying to a four-year institution. The report found that “the total published cost of attendance at even the cheapest New Jersey public 4-year institution represents well over half of the household median income for black or Latinx families in New Jersey.”

And even though New Jersey balances these high costs with generous financial aid packages, the report found that the lowest-income students still pay a higher net price after financial aid than low-income students in other states. Most distressing, the authors wrote, is the fact that one-third of New Jersey community college students don’t apply for financial aid at all either because they struggle with the process, miss deadlines, or are completely unaware that the aid grants exist.

Not enough being done for community colleges

Still, many of these students look to two-year community colleges as a way to get an affordable education. Unfortunately, the report notes, these two-year institutions often underperform and are under-resourced, putting black and Latino students further at risk of dropping out before completing their degree or graduating with a degree that does not meet the workforce needs in the state.

Part of Gov. Phil Murphy’s campaign platform was a “free community college” program to increase access to the state’s two-year county schools. Last year, he launched the first phase of this process, making grant money available to select schools. The only problem, according to the ERN report, is these schools do not receive enough state funding and resources to adequately educate and graduate their students.

In a presentation of their findings, the report’s authors wrote that “while intuitively cheaper from a taxpayer perspective, community colleges are markedly less efficient.”

The data shows nearly half of New Jersey black and Latino college students attend public two-year institutions, where all things being equal, their chances of graduating are 30 percentage points less than their peers with similar academic credentials attending four-year schools. In addition, the report found that over 85 percent of first-time, full-time black and Latino two-year students at New Jersey community colleges leave school without a degree and often with student loan debt.

Dannenberg said that while Murphy’s plan is well-intentioned, getting more students to attend community college is simply not enough. A more effective plan would increase state aid and support to both two- and four-year colleges to allow them to better serve students, he said, rather than eliminating tuition costs to schools that leave black and Latino students with an insufficient degree to meet the state’s workforce needs or without a degree at all.

“Many workers need more than a community college education,” Dannenberg said. And the data proves that point. New Jersey has one of the lowest projected needs for two-year degrees or less. Indeed, the report found only 26 percent of jobs created in the state require these types of degrees. “But that’s not to denigrate community colleges,” he added. “They need more support and love. They shouldn’t be treated as the stepchild by the state.”

‘…arbitrary, inequitable, inefficient’

Dannenberg said state appropriations to higher education institutions in New Jersey are also out of whack. “We’re supportive of an early upfront guarantee of college affordability in the state and I’m certainly not opposed to free community college. But we’d really like to see a statewide college affordability plan that reaches two and four year institutions and that improves aid to all those institutions.”

New Jersey’s system for funding two- and four-year colleges is, according to the report, “arbitrary, inequitable, and inefficient.” The amount a school receives each year is based solely on how much it’s received in the past instead of the makeup of the student body and the individual needs of each school.

The latest numbers show that the state spends a combined $1.5 billion a year in general operating funds on public colleges and financial aid programs. But that funding is not distributed according to demonstrated need. The report uses Rowan University and Montclair State University to illustrate this point. Rowan, the authors point out, serves a statistically less needy student body than Montclair State (as evidenced by students who are eligible for a needs-based federal Pell Grant) but it gets three times more operating aid per student from the state than Montclair State — $7,146 versus $2,359 per pupil.

The Office of the Secretary of Higher Education acknowledged to the report’s authors “that there is no clear policy rationale explaining, much less justifying, current marked inequities in the distribution of state funding to public institutions of higher education.”

Secretary of Higher Education Zakiya Smith-Ellis is trying to change this, however. In a recent interview with NJ Spotlight, Smith-Ellis outlined her plan for an “outcomes based funding” approach that would take into account priorities like degree completion and serving minority students.

A lot of money goes to for-profit colleges

The state also funds schools through tuition-aid grants (TAGs) to students which pass through to the colleges and through state programs like the Education Opportunity Fund (EOF) which provides financial support as well as services like counseling and tutoring to low-income students.

But, although TAGs make up nearly 92 percent of the state’s student assistance budget, there are serious issues with that system, the report shows.

For one, TAGs only cover tuition — not fees, books, supplies, or the incredibly costly room and board. What’s more, the report shows nearly a third of TAG resources go to private institutions, including millions doled out to some of the richest institutions in the state.

According to the data, over $120 million (33 percent) of TAG’s dollars go to private colleges serving only 18 percent of all New Jersey students and over $16 million of TAG’s money goes to for-profit colleges. Even schools with huge endowments like Princeton University — it has a $22 billion endowment — receive TAG money. The report’s authors point out that a student going to a private, nonprofit institution like Princeton gets nearly 75 percent more TAG funding than a similar student attending a public university like Stockton College, and 25 percent more than a student attending Rutgers.

Meanwhile, the EOF program, which the report refers to as the state’s “hidden higher education gem” is chronically underfunded despite demonstrating better results for students. EOF provides flexibility in funding that TAG lacks: It doesn’t just give money for tuition, it requires institutions to support students with childcare, academic advice and tutoring, not just help paying bills.

Gap in graduation rates

The report found students receiving an EOF grant have the highest graduation rate in the country when compared to students in 15 similar programs in other states. The six-year bachelor’s degree attainment rate for low-income EOF recipients in New Jersey, Dannenberg said, is approximately 55 percent compared to the overall New Jersey TAG completion rate of only 32 percent.

For those black and Latino students who have earned grades high enough to give them access to colleges, are granted financial aid, and make it into a college or university in the state, success still can be elusive. The ERN report found a significant gap in graduation rates between black and Latino students and their white peers in the state.

The report notes that completion rates at New Jersey’s public four-year institutions of higher education on the whole are much higher than the national average with the exception of Latino students. White students in New Jersey have a graduation rate of 72 percent (10 percentage points higher than for white students nationwide), black students graduate at a rate of 54 percent (14 percentage points higher than the national rate for black students) and Latino students graduate at 58 percent (4 percentage points higher than the national rate). However, despite these successes, the white-Latino graduation gap, is still wide enough to place New Jersey eighth in the nation in terms of Latino-white degree completion. That means inequities persist in the system despite raising graduation rates across the board.

The importance of income

Income also plays a major part in how well a minority student will do in school. The report notes that students who attend four-year colleges part-time and work are nearly five times more likely to drop out as their peers who can afford to work less and attend school full-time.

With these findings now public, Dannenberg said he hopes policymakers will take note. In that context, it is of note that the governor’s strategic plan for higher education is expected to be released soon.

The report notes in its conclusion that “if New Jersey does not address systemic inequities in college preparation, access, affordability, and completion, it risks excluding black and Latinx individuals, who represent approximately one-third of the state’s population (and 41 percent of the state’s 0-25 year-old future generation), from the state’s economic future — dramatically worsening racial inequality.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.