Mütter Museum is reviving a 1918 Philly parade that sparked a killer flu outbreak

Philadelphia was one of the worst-hit cities during the 1918-1919 flu pandemic but no memorial exists for them. The Mütter Museum is changing that.

-

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas, probably early 1918. (OHA 250: New Contributed Photographs Collection, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine)

-

“Preparing to Bury City’s Influenza Victims,” undated clipping from a scrapbook of the influenza pandemic in Philadelphia compiled by an unknown person, August 1918–March 1919. (Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia; acquired October 19, 1919, through the Exchange Program of the Medical Library Association)

-

Hull of an experimental F6L flying boat under construction at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, with influenza precaution sign in background, October 19, 1918. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph, Catalog # NH 41731, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.)

-

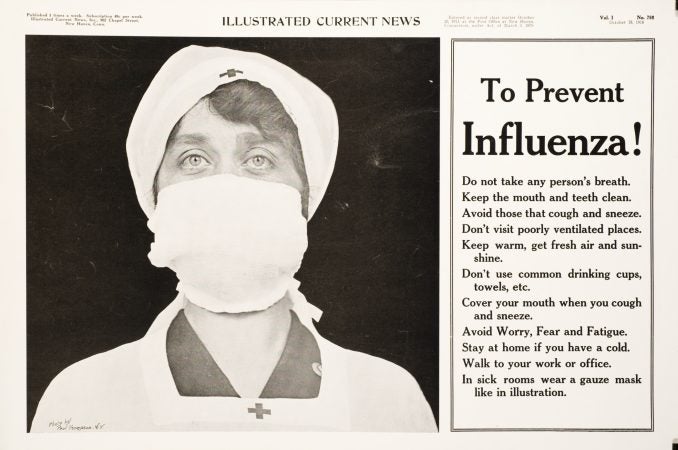

To Prevent Influenza! Illustrated Current News, New Haven, Conn., 1918. (U.S. National Library of Medicine)

-

Sailors are treated in the isolation ward of the Naval hospital in Gulfport, Mississippi during the influenza epidemic, 1918/19. At least 25 million people in the United States were infected (one quarter of the population) and more than 700,000 people died in the United States alone. (NH 116532 courtesy of the Naval History & Heritage Command)

-

A Naval Aircraft Factory float heads south on Broad Street in Philadelphia. This parade, with its associated dense gatherings of people, contributed significantly to the massive outbreak of influenza which struck Philadelphia a few days later. (NH 41730 courtesy of the Naval History & Heritage Command)

-

Influenza ward, Walter Reed Hospital, Washington, D.C., about Nov. 1, 1918(Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Saturday evening, hundreds of people are slated to march from South Philly to City Hall tracing a four-mile route some 200,000 people marched on Sept. 28 — just over a century ago.

The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia is hosting tomorrow’s “Spit Spreads Death” parade.

The organizers don’t plan to duplicate the public health crisis that followed that 1918 parade. Some 12,000 people died in Philadelphia over the six weeks that followed.

The Spanish flu pandemic was already wreaking havoc across the U.S. in September of that year and public health officials warned of the dangers that any mass public event could bring.

But Philadelphia hosted a parade at the end of that month to sell war bonds anyway.

“Because World War I was in progress and no one wanted to get in the way of pushing the war effort, raising money for the war effort,” said Robert Hicks, director of the Mütter Museum. “The flu was a side story that was not talked about.”

The parade exacerbated the spread of the flu in Philly. Within 72 hours of the Liberty Loan fundraising parade, hospitals were inundated with patients.

A pandemic that would claim some 20,000 lives in the city over six months was in full swing, hitting low-income communities and young people the hardest.

The city, which had one of the highest flu mortality rates in the country, fell into a state of chaos.

“It became impossible to find coffins, people had to be buried in mass graves,” said Matt Adams, a UK-based artist and co-founder of the art collective Blast Theory. The Mütter Museum commissioned Adams’ group to host Saturday’s remembrance march.

Despite the toll, flu fatalities had on the city, the end of World War I that November overshadowed the growing crisis. The victims weren’t honored with so much as a plaque or statue.

“The mood of the country was really to celebrate and so those people who’d lost loved ones to the flu didn’t really have a chance to honor them and didn’t really have a chance to acknowledge them publicly,” Adams said. “It was seen as the patriotic duty was to celebrate the end of the war.”

Saturday’s event aims to correct that oversight.

Not a typical Philly jawn

The parade is a precursor to a Mütter Museum exhibition all about the flu outbreak opening mid-October.

“It’s not like your regular parade, it’s no marching bands, no puppets,” Adams said. “It’s not really for spectators. It’s for participants.”

Participants can go online and pick a person who died of the flu to honor. The list comes from Oct. 12, 1918, the deadliest day of the pandemic when some 750 people died in the city.

The Crossing, Philly’s local Grammy-winning choir, will be heard solemnly singing the names of the victims through parade-goers’ smartphones — Anna Golden (28), Thelma Schumann (1), Marion Bernice Barth Lingle (22), and hundreds of more names.

The piece, written by Pulitzer Prize and Grammy-winning composer David Lang, also offers some practical advice.

“Beware of those who are coughing and sneezing… avoid crowded streetcars… walk to the office if possible…avoid crowds,” sings the choir in slow, spread out sections of music.

Four white 20-foot wide sculptures will also act as speakers. The panels will be illuminated by white light and pushed forward by teams of people.

The event will end with a health fair that celebrates advances made in modern medicine, including the discovery of an effective flu vaccine, which people can get at the fair. It also celebrates the unglamorous profession of public health workers.

“There aren’t many Hollywood films about people working in public health and yet those people save millions of lives year in and year out,” Adams said. “We want to take a moment to publicly honor them.”

“Spit Spreads Death” takes its name from a public health poster that was discouraged spitting at the time of the pandemic.

The exhibit will bring visitors to 1918-1919 Philly, recreating the look and feel of the city at the time while sharing the stories of those who fell ill.

But it’s also meant to get people thinking about how diseases can strike at any moment despite medical advancements. The conversation aims to start conversations about the government and the public’s role in fostering public health.

“We expect anyone coming through this exhibition in its lifetime will have somewhere cooking in their mind some news article they’ve heard of about a disease outbreak,” Hicks said. “It could be Ebola, it could be measles since that’s making a resurgence in places where people have not gotten vaccinated, or it could be the flu.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.