How minstrel tune became the signature song of the Mummers Parade

Once an international star, the Black composer of “Oh Dem Golden Slippers” died penniless in Philadelphia.

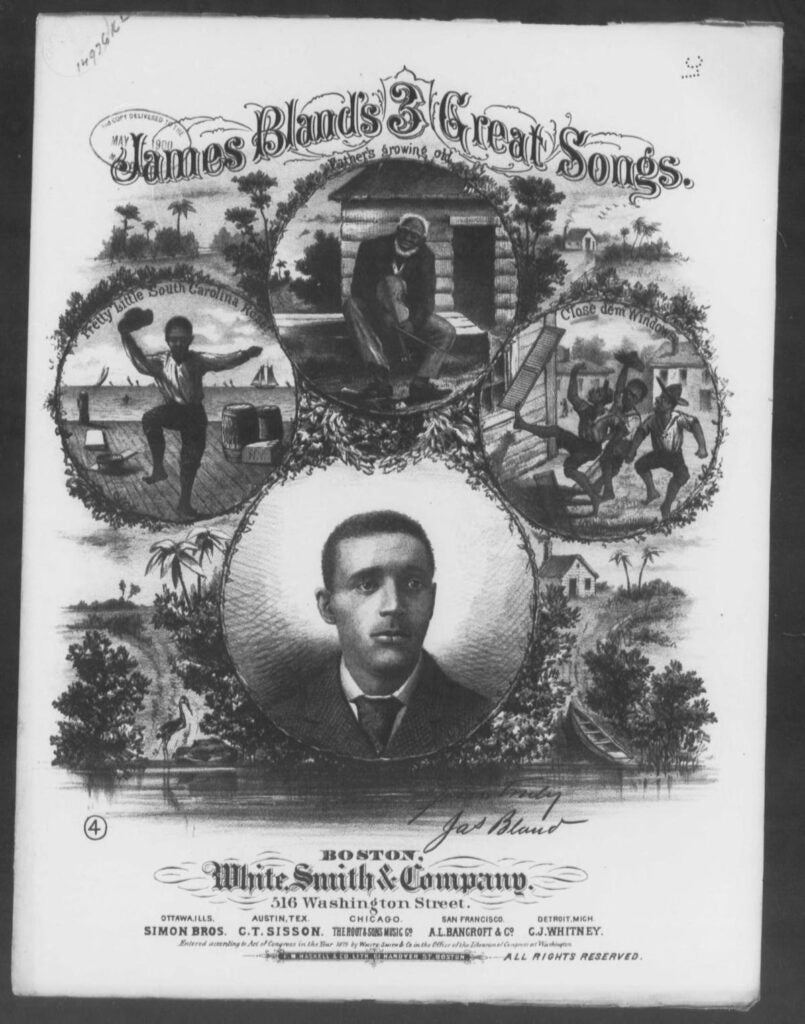

Sheet music cover for 'James Bland's 3 Great Songs, 1879. Scanned from Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America by Robert Toll.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

For almost 120 years, the song “Oh Dem Golden Slippers” has been heard on Broad Street on January 1, although it’s unlikely that most Mummers during the early years of the parade knew the author was living in their midst.

James A. Bland was one of the most prolific minstrel songwriters of his day, having reportedly written hundreds of songs in the late 19th century, although relatively few were published. The Black composer was considered a rival talent to the country’s preeminent writer of popular song at the time, Stephen Foster.

Bland is best remembered for “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” which became the official state song of Virginia for more than 50 years. When the enormously popular “Carry Me Back” was published as sheet music in 1879, it was packaged with two other songs: “Oh Dem Golden Slippers” got third billing.

“I would consider it a B-side track,” said Rhae Lynn Barnes, an assistant professor of history at Princeton University. “You would hear it if you bought ‘Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,’ but it was not something people were fanatical about.”

Barnes is the author of the forthcoming book, “Darkology: The Hidden History of Amateur Blackface Minstrelsy and the Making of Modern America,” expected in 2025. She said that in the late 19th century every entertainer, Black or white, was involved with minstrelsy to some degree.

“There’s a saying that the drain of the minstrel show got everybody of that generation,” said Barnes. “Whether you were trying to be a stand-up comedian, a singer — no matter what, that was ultimately the only place for you.”

Bland was born in 1854 as a free Black person in Long Island, the son of one of the first college-educated Black men in the country, Allen Bland. James followed in his father’s footsteps and began studies at Howard University, but ran afoul of strict school rules forbidding participation in musical theater. It’s unclear if he dropped out or was kicked out.

Bland embraced the minstrel show, America’s most popular form of entertainment at the time, which centered on exaggerated stereotypes of Black people. Audiences typically wanted to see white actors wearing blackface makeup performing Black mannerisms, not a Black artist performing at the top of his craft, so Bland had to apply blackface to his black skin during performances.

“Oh Dem Golden Slippers” is a parody of the spiritual “Golden Slippers,” popularized by the Fisk Jubilee Singers of what would become the historically Black Fisk University. The song is about the finery one will be wearing when they “join the heavenly choir,” or, in the case of Bland, when they “ride up in the chariot in the morn.”

Barnes said “Oh Dem Golden Slippers” anticipated a future form of popular music: ragtime.

“It is very upbeat. Its tempo is very much derived from minstrelsy. It has a mix of sounds that come from the cakewalk, which is another form of blackface performance,” said Barnes. “When you listen to the music, you can see that he is playing around with tempos … that makes people want to move and to march.”

Bland wrote “Oh Dem Golden Slippers” in 1878, just as America’s Reconstruction experiment to uplift newly freed Black people had ended, and many states were passing so-called Jim Crow laws to segregate and oppress Black citizens. Barnes points out that the song’s theme of fancy clothes and a promising afterlife would have resonated with Black life of the time.

“These things that become synonymous with Philadelphia pride and New Year’s, and have become the soundtrack to our lives, actually have these really deep and rich layers that we can peel back,” she said. “How are these stereotypes constructed? Why were they adopted by primarily white ethnic groups in the 20th century?”

How did a somewhat obscure song written for the minstrel stage become the signature song of the Mummers?

After a long stint working and touring in Europe, Bland’s career was sputtering by 1901. He moved to Philadelphia to take a job with Frank Dumont at one of the last dedicated minstrel theaters in the country, Dumont’s Minstrelsy at what used to be the 11th Street Opera House.

Dumont was not only one of the foremost minstrel proprietors of the time, but was also in the business of teaching and promoting minstrel performance to amateurs. In 1899 he published a how-to book, “The Witmark Amateur Minstrel Guide and Burnt Cork Encyclopedia.” The introduction promises the book is “compiled and arranged to instruct, suggest, and prepare a minstrel entertainment, perfect in all its details — from the ‘blacking up’ of the artists to the fall of the curtain upon the concluding burlesque.”

Dumont’s nephew, Charles Dumont, likely would have seen Bland perform in his uncle’s theater, and learned from the book how to stage a minstrel show with his friends. In 1905 he put together a string band for the New Year’s Day parade, performing “Oh Dem Golden Slippers,” the first known performance of the song by Mummers.

Other staples of minstrelsy, like the cakewalk and blackface, also became part of Mummery. Only after a protracted fight did the Mummers agree to officially give up blackface in 1965, although it still has continued to appear, as recently as 2020.

It’s not known if Bland, himself, had any involvement with the early years of Mummery, but since the tradition has strong working-class Irish origins, he likely did not. Once commanding $10,000 a performance season, his life ended badly, sick and penniless. In 1911, at age 57, he died of tuberculosis and was buried in an unmarked grave in Merion Memorial Park, in Bala Cynwyd.

Years later the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) raised funds to erect a memorial tombstone for Bland. The carved stone makes no mention of “Oh Dem Golden Slippers,” but prominently displays his more popular “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny.” The tombstone was funded in part by the state of Virginia.

Bland is also prominently memorialized in the Mummers Museum on Washington Avenue, for his contribution to the folk tradition.

Americans of a certain age may remember a version of “Oh Dem Golden Slippers” used in a 1970s television ad selling Golden Grahams cereal, but in Philadelphia the song has been synonymous with Mummery for over a century.

“What starts to happen around the 1970s is the song shifts from being seen as part of mainstream popular culture to American folklore,” said Barnes. “Once something is deemed American folklore, in some ways, it’s protected. You can then teach it to children. You can put it into nursery songs. You can mass distribute it in cartoons. That’s one of the ways in which it becomes even further entrenched in our American cultural psyche.”

“Also just the truthful fact that songs are meant to stick in your head. You can’t get them out,” she said. “Once it was relegated to Philadelphia folklore and tradition, it takes on this new life and becomes a soundtrack to the city. It’s not going anywhere.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.