Michener’s Bertoia exhibit focuses on monoprints taking shape in sculpture

Listen-

The Harry Bertoia exhibit at the Michener Museum. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Michener Museum Director and CEO Lisa Hanover curated this show of Harry Bertoia's monoprints, jewelry and sculptures. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Harry Bertoia's chair designs are considered to be part of the modern furniture movement. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Roberta Hurley of Lambertville, N.J., fan of sculptor Harry Bertoia, appreciates the sound of one of his tonal sculptures on display at the Michener Museum. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

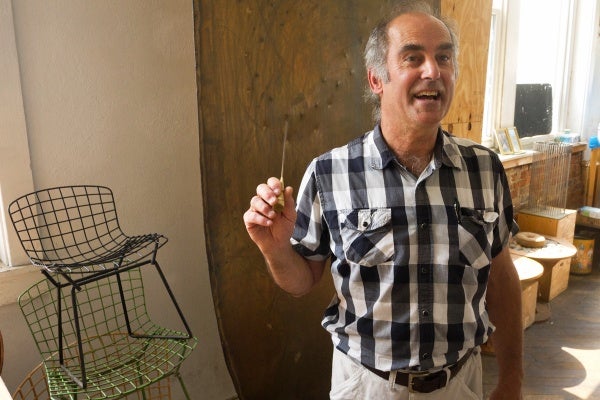

Harry Bertoia's son, Val, demonstrates one of his father's gong sound sculptures outside of his studio in Bally, Pa. (Charlie Kaier/WHYY)

-

Val Bertoia continues his father's tradition of crafting sound sculptures at the Bertoia Studio in Bally, Pa. (Charlie Kaier/WHYY)

-

A dandelion hanging sculpture in the shape of a sphere hangs at the Knoll furniture company in East Greenville, Pa. (Charlie Kaier/WHYY)

-

Carol Connell, account manager for Knoll, sits in the Bertoia Diamond Chair. (Charile Kaier/WHYY)

Harry Bertoia made enormous architectural sculptures for buildings around the country and tiny jewelry pieces the size of your finger. But he is perhaps most well known for his brass sculptures that resonate like bells.

“People come out of the woodwork around here when you mention Bertoia,” said Lisa Tremper Hanover, the president of the Michener Art Museum. “‘I’ve got a Bertoia! ‘I’ve got a Bertoia!’ ‘I ruined a Bertoia because I didn’t know what I had!’ But among the pantheon of American sculptors, he’s right up there.”

Bertoia also made monoprints, which he used as studies of shape and line. Hanover noticed many of Bertoia’s monoprints feature shapes that would become the basis of his sculptures, and she curated the exhibit “Harry Bertoia: Structure and Sound.”

The show is a modest size, with the walls of two gallery rooms ringed with monoprints: abstractions of line clusters and thick, sensuous shapes. In front of the prints are the objects that seem to have evolved off the page. There are cases of silver jewelry, a ball of radiating wire hanging from the ceiling, an irregular grid of bronze plates and several sound sculptures.

“What I’m doing with the installation is bringing together objects that relate to the monoprints, so you see how the monoprints have influenced the 3-D sculptures,” Hanover said. “He’s playing with organic plane shapes and using vertical lines to see what might work aesthetically and aurally.”

The sculptures are clusters of thin bronze or stainless steel rods planted in a base. When you push the rods they sway and gently knock against each other. Of course, you’re not supposed to touch them because they are art.

Chairs made of air

In 1950, Harry Bertoia, born in Italy, was living in Southern California and developing a name as a fine artist. He suddenly moved to Pennsylvania to make office chairs. He accepted an offer by Knoll, the furniture company, to come to East Greenville in Berks County, where he designed a set of modernist chairs made of contoured wire.

“They are mainly made of air,” Bertoia said of them. They are still one of Knoll’s most popular products.

“Now, into a fourth generation, we deal with students who save their money just to buy this furniture,” said Carol Connell, an account manager at Knoll. A native of East Greenville, she has worked for the company in various capacities since 1978 and married Bertoia’s former studio assistant.

Bertoia worked at Knoll for only two years, designing just one line of furniture. But the small-town, rural life of central Pennsylvania grew on him. He bought a farmhouse with a barn near Bally, a few miles from East Greenville, and stayed there until his death 25 years later.

He was never far from Knoll, and Knoll was never far from him. The international company—which still retains its headquarters amid the soybean fields of East Greenville—often brought clients and VIPs to visit the famous sculptor’s studio.

Soothing the spirit with sound

“He had a big gong. At the entrance, he had a leather-wrapped mallet and would ask someone to bang the gong before entering,” Connell remembered. “He was an amazing man. I loved him.”

That gong still greets visitors to the studio in Bally where his son, Val Bertoia, continues to make sound sculptures and gives daily tours.

“He worked with metals all his life and career,” Val Bertoia said. “It was using metals first to make the physical human body comfortable and still using metals later in life to make the human spirit comfortable with sounds.”

Harry Bertoia made hundreds of sound sculptures, arranging dozens inside a barn on his property where he made recordings. Called Sonambients, he released seven LPs filled with layers of metallic resonance struck randomly. The sounds are loud, formidable and meditative.

“In this way, when a sound comes, you cannot quite control it. It has its own life. You have to sway along with it,” Bertoia said in the 1977 short film “Sonambient.” “They are very powerful. They seem to be the sounds of the bowels of the earth.”

A 10-minute demonstration of the Sonambient sculptures is included on the tour of the Bertoia barn. Val Bertoia said the sound sculptures do not make music—you cannot play them like instruments. Rather, his father was trying to make sound uncontrollable.

“There was inspiration from nature, birds, cicadas, even frogs in a swamp,” Bertoia said. “He would hear these sounds in nature, and make metallic versions.”

Visitors to the Michener museum in Doylestown are not allowed to touch the sculptures. But if you ask the museum docents, they will don white gloves and set Harry Bertoia’s resonated rods in motion.

“Harry Bertoia: Structure and Sound,” continues through Oct. 13 at the Michener Art Museum, 138 S. Pine St., Doylestown, Pa.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.