Looking across time: A yearlong study will focus on Delaware communities hit hardest by COVID-19

Nine communities will be researched for a year to determine behavioral factors contributing to the virus. The aim: to empower them to protect themselves.

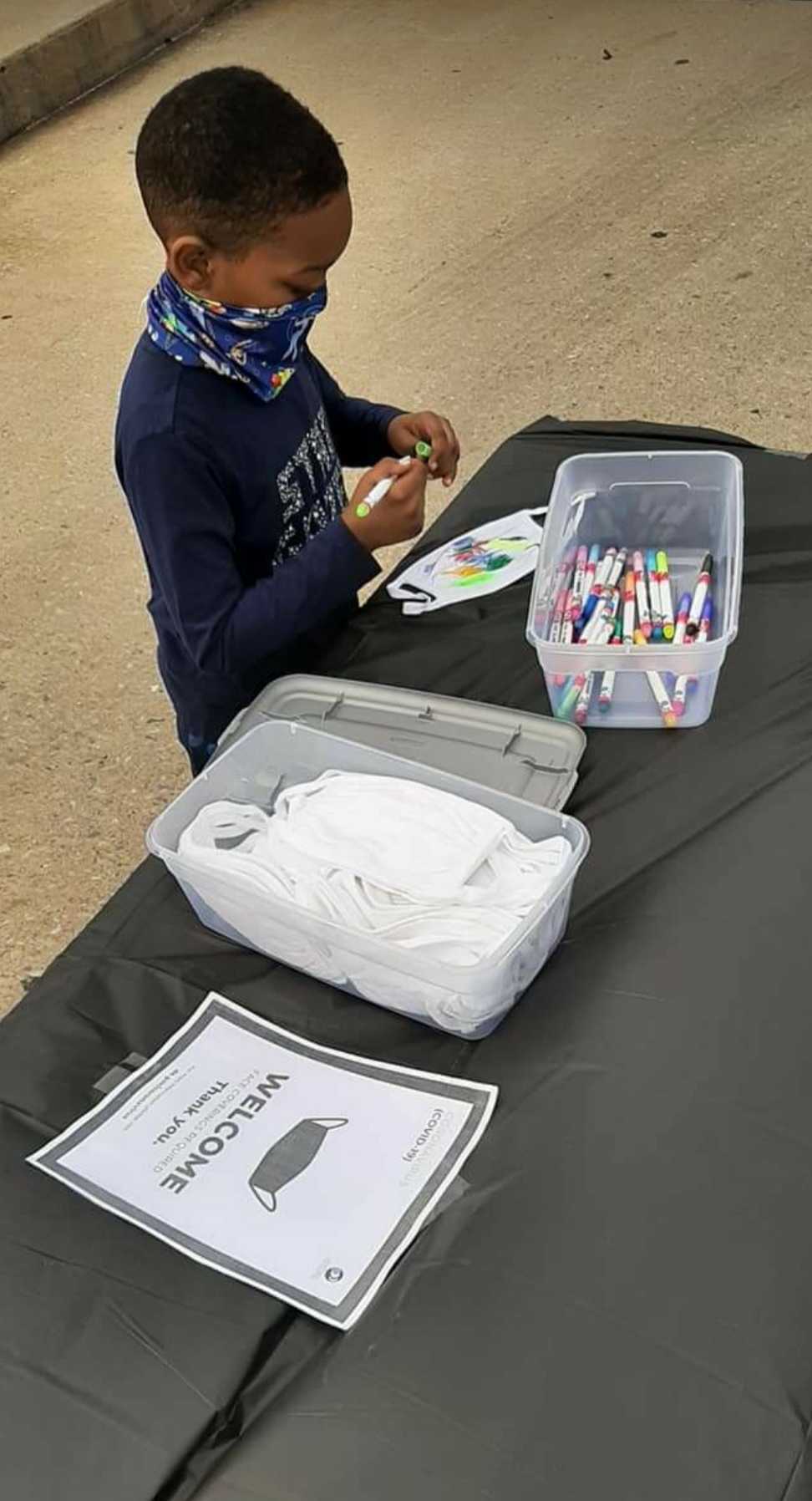

West Side Grows held a Halloween event for the children of Wilmington's West Side neighborhood. Masks were given distributed to attendants. (Courtesy of Jason McCall)

Delaware State University is making plans to research social and behavioral factors contributing to COVID-19 in underserved communities throughout the state.

The university will use a two-year, $1.15 million National Institute of General and Medical Sciences (National Institutes of Health) grant. It is one of 32 institutions to receive the NIH grant, which supports research about COVID-19 testing patterns, attitudes, and risk-reduction behaviors among underserved and vulnerable populations.

Preparation for the study comes as coronavirus cases are surging throughout the nation and in Delaware, whose COVID-19 numbers have been steadily increasing over the last month. Last week, the state saw its largest single-day case total since mid-May.

Researchers plan to be in the field and recruit participants by January.

“We can’t always change environment, and it’s harder to change other factors related to health and well-being, and some of those socioeconomic factors may also be difficult to change. But we can change behavior, and that’s key, particularly with something like COVID, to protect ourselves and people we live with,” said Dorothy Dillard, one of the study’s researchers.

“What’s great about doing a longitudinal study is that we will be able to look across time to see if there are some behavior changes that occur,” Dillard said. “And it’s critically important to understand how to get health information to people in underserved communities in a way that they can access and respond to, especially as we look for a vaccine to be available within a year.”

The university, located in Dover, will focus on nine underserved communities across Delaware that are facing disparate incidents of coronavirus infections. The study will target 1,200 participants who will be followed for one year, participate in interviews and be tested for the virus every four months.

The Sussex County communities participating in the study are Georgetown, Bridgeville and Seaford. In that southernmost county, at least half of the study’s participants are expected to be Latinos, who have been disproportionately affected by the virus.

The Kent County communities participating are West Camden, West Dover and Harrington. The New Castle County communities are Northeast Price’s Corner, Wilmington’s West Side and Wilmington’s Riverside community, where COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting people of color.

These communities were identified for their characteristics, demographics, and health index, which is what public health officials use to identify communities with higher health risks and illness.

The researchers want to inform public health officials and health care providers about their findings in the hopes there will be interventions tailored for these communities. Latinos in Delaware contract COVID-19 at a rate four times that of white state residents, and Black Delawareans are testing positive twice as often as white residents.

“We are aware of the race disparities and health indicators. Those are pretty well-established, and we’ve been playing around with how to address that better. But the pandemic is going to take advantage of the most at-risk, so it’s not surprising we’re seeing higher rates of COVID in communities that were already at risk for other health issues,” Dillard said.

“So if we already have disparities and haven’t figured out how to address those more effectively and to begin to close that gap, then it’s no surprise that something this contagious and pervasive will hit hardest on the communities where we will be doing our study.”

Wilmington, where COVID-19 ‘exacerbates’ disparities

Delaware State will partner with the Wilmington City Advisory Council, which was launched in 2016 as a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention after it studied gun violence in Wilmington. During the pandemic, the group has been working to ameliorate the adverse impact of COVID-19 on the city’s Black and Latino communities, and has since expanded its work to New Castle County.

“When we look at all the social determinants associated with weaknesses within communities, race predominates in terms of disproportionate employment opportunities, income, housing, health, all those outcomes are lower within the Black and brown communities,” said the advisory council’s Dr. Henry Smith.

He added that high rates of COVID-19 in Wilmington also are in ZIP codes where there is a higher incidence of gun violence.

“What COVID-19 has done is simply to exacerbate those disparities and made them worse, if you will, because now with COVID-19 the impact on employment has hit Black and brown people harder, and the impact on health has impacted Black and brown people harder.”

The advisory council’s Gwen Angalet said residents most affected by the virus often have essential jobs, which puts them at greater risk during the pandemic.

“We have people because of no fault of their own living in very condensive housing situations, they work an essential job, they have to go to work to get their paycheck, they’re stressed for a variety of other reasons, so you set the stage for the kind of situation we have,” Angalet said.

Rich Parson, of Kingswood Community Center in Wilmington’s Riverside neighborhood, pointed to several disparities in the ZIP code that was chosen for the Delaware State University study.

“I know for sure that the Riverside area is one of the most dangerous, and has so many systematic problems than anywhere else in the city of Wilmington. It’s a food desert. There’s no grocery stores in the area. You have a lot of liquor stores and a couple dollar stores and corner stores that don’t have a variety of healthy food,” he said.

“A lot of [the jobs] are fast food, a lot of mom-and-pop stores around the city had to close their doors because of the lack of people being able to come in and spend money and because of the nature of the pandemic,” he added. “A lot of them lost their employment, and of course when you lose employment you don’t have the money to pay for necessities.”

Parson described it as a “snowball effect,” shedding light on how many neighborhood stores lack access to hand sanitizer, for example.

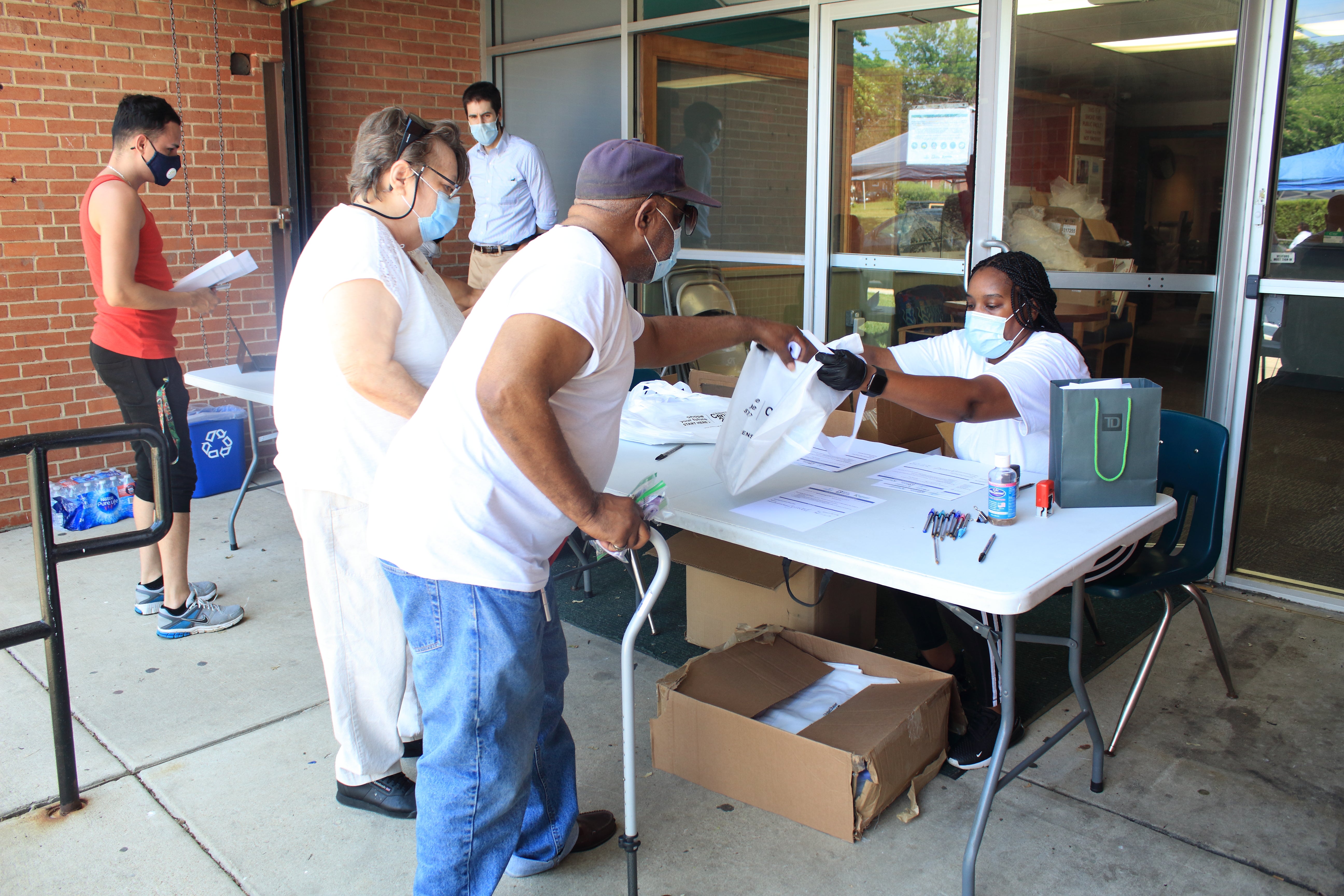

Riverside has been a hot spot for COVID-19 cases. Kingswood Community Center has hosted coronavirus testing events, and 13% of individuals tested there have been positive for the virus so far.

“It’s extremely sad when you think about some of the community members who weren’t able to get masks unless advocating for them from different hospitals or community centers that brought that in,” Parson said. “It’s an alarming rate, and it doesn’t even speak to half of our residents because less than half of our residents are coming to get tested.”

Riverside residents are at risk because they don’t have adequate resources to protect themselves, he said, and because they live in close quarters in public housing.

“On a day-to-day basis, they run into so many people, so if they do get infected they will bring it back into the community where they live,” Parson said.

Jason McCall, of the community organization West Side Grows Together, said he believes the West Side of Wilmington was also chosen for the Delaware State study because of its low incomes, inadequate housing, and lack of access to transportation.

“The West Side of Wilmington had plenty of disparities prior to the pandemic, and the pandemic just made them even worse and brought them to the forefront,” McCall said. “So they’re actually being noticed now, so the emphasis is now going to be on how do we correct these blights going forward? Not just to show up during the pandemic, but after the pandemic as well.”

McCall said there aren’t enough testing sites in the West Side of Wilmington, and there’s a lack of knowledge among some residents about actions they can take to remain healthy.

“I feel like sometimes the West Side is forgotten about, and I honestly do feel like that’s based on the demographic makeup of the area,” he said. “The residents in the area aren’t adequately represented at the table. They don’t have enough people championing their causes, and even when their causes are being championed, they often fall on deaf ears or they get pushed to the background to a later date.”

West Side residents can get tested at a CVS Pharmacy on Pennsylvania Avenue in Wilmington, but McCall said it would be more convenient if there were a testing site at a Rite Aid on Fourth Street, in the Adams Four shopping center.

“With the CVS site, a lot of people aren’t able to walk that far or get transportation to go to that location,” he said. “With the Rite Aid location, it would be a more centralized location for the majority of the West Side area, and that’s a very high-volume area traffic-wise, so it would be easier to get to.”

McCall said he would also like to see a mobile testing van in the neighborhood.

Advocates in Wilmington say there needs to be increased mask distribution, increased testing, and more compliance with contact tracing. They also said there needs to be improved access to Chromebooks, laptops and Wi-Fi for students doing virtual learning.

There’s also room for improvement when it comes to personal behavior, some say.

“When I drive around, what keeps me up is seeing too many individuals who are not complying fully with those CDC requirements,” said the Wilmington City Advisory Council’s Smith. “I see too many people who are not wearing a mask, who are not engaging in social distancing, and I see a lot of that among young people in those communities I referenced earlier.”

He added that his organization also has discovered some non-compliance among police officers. The advisory council spoke to several police departments and was told that police officers are required to wear masks, but that there isn’t a 100% compliance rate.

Angalet of the advisory council added that some individuals don’t think COVID-19 is a serious threat, and believe that the virus won’t affect them if they’re young.

“They don’t think about how if they do get COVID they can spread it to others, especially elderly people. It concerns me that we had an uptick in COVID cases among our residential facilities, that’s just not a good sign now [that] we’re approaching winter,” she said.

Rural Sussex County, hit by job loss, working conditions

In Delaware’s southernmost county, Delaware State University will work with the Sussex County Health Coalition, which will direct researchers to partners with boots on the ground.

The coalition’s executive director, Peggy Giesler, said Sussex County faces some distinct challenges when it comes to the pandemic.

“You have populations who work in low-wage jobs that are front-facing for the community, whether that’s food distribution, meaning poultry plants, whether it was serving the community, working in different settings where they come in contact with a lot of community members,” Giesler said, adding that those workers then go home and unintentionally spread COVID-19 to other people in their homes.

It’s possible that people who tested positive for COVID-19 might not have had the ability to isolate themselves from other people, whether it’s because of their housing situations or their jobs, she said.

“I think we make judgments about everybody’s access to health care and everybody’s ability to shelter in place and quarantine, and we don’t look at the big picture of if they have the ability and knowledge to do that,” Giesler said. “Or they might have to go to work to survive, and they may have been put in work situations that at the time hadn’t caught up with the mandates.”

She said she would like the study to evaluate whether residents received the appropriate information they needed to protect themselves at the beginning of the pandemic, or whether that information was second-hand.

“I think that’s part of what DSU wants to do. They want to study: Are there certain populations we can get to, or they didn’t get quite the right information to, and how did that spread and how can we mitigate that next time? So, if we’re in another pandemic or another situation like this, we will have better systems in place to address it and eliminate the ability for the spread to happen as quickly or in certain geographic regions or in a certain way,” Giesler said.

In Sussex County, COVID-19 has disproportionately hit Latino communities, who in the rural areas have essential jobs where the tools to protect workers might not have been available.

Jennifer Fuqua, executive director of La Esperanza in Georgetown, one of the towns the university will study, said there have been major financial implications for some Latinos in the area.

“It really has exposed how close to the edge some families are, in particular some members of the immigrant community, Hispanic, Haitian, and others. And what we saw at La Esperanza was how much help people needed when they couldn’t go to work, when it was difficult for them to go outside the house,” Fuqua said.

La Esperanza has helped by delivering food once a week to people who are quarantined or who have issues with transportation, and by assisting with shelter and workforce development, she said.

“My biggest concern is if we don’t continue to provide a safety net when the different kinds of CARES Act stimulus money is gone,” Fuqua said.

In partnership with First State Community Action, La Esperanza has provided more than $150,000 in philanthropic grants to those in need.

“A lot of these families don’t qualify for that [federal] assistance. So people are at the edge of losing their homes, and people will go homeless. So we do need to provide that safety net for people,” she said. “We actually found new pockets of people who have needs, who have never reached out before because a lot of folks are really quite proud and not interested in asking for help, but during this time they’ve had to.”

Post-pandemic and post-study

The study offers health experts and community advocates another opportunity to retrieve the data needed to better support families in the communities being researched. But the Wilmington advisory council’s Smith said it won’t be a cure-all.

“This data will provide more information and hopefully that information can lead to improved options in the future, but I don’t see it as the silver bullet that’s going to be the cure-all of these entrenched circumstances in which these folks live,” he said.

Smith added that he’s concerned underserved communities will be forgotten once the pandemic is over.

“What happens after COVID is gone? Do we simply say, ‘Thank goodness COVID is gone,’ and we’re still left with those awful conditions that create significant disparities? Because those disparities to the extent they remain unaddressed will one day confront another COVID-like situation,” he said.

“And the folks who can do something about that, the political leaders, the philanthropic leaders, the corporate leaders, it will be my great hope they will take the lessons from COVID to understand the need to discontinue those disparities, because they ultimately cost society significantly,” Smith said. “It’s an undue burden on society with these disparities left unchecked.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)