Long-dormant Bertoia sculpture transplanted to Chestnut Hill

Listen-

-

(NewsWorks file photo)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

A public fountain installed in West Philadelphia for three decades, then hidden from sight for 16 years, has been transferred to the Chestnut Hill neighborhood.

Harry Bertoia, a sculptor famous for designing midcentury furniture, was commissioned in 1967 by the city of Philadelphia to make a sculptural fountain for the old Civic Center building in University City. The center was being expanded at the time, and the city’s One Percent for Art program required creation of a piece of public art.

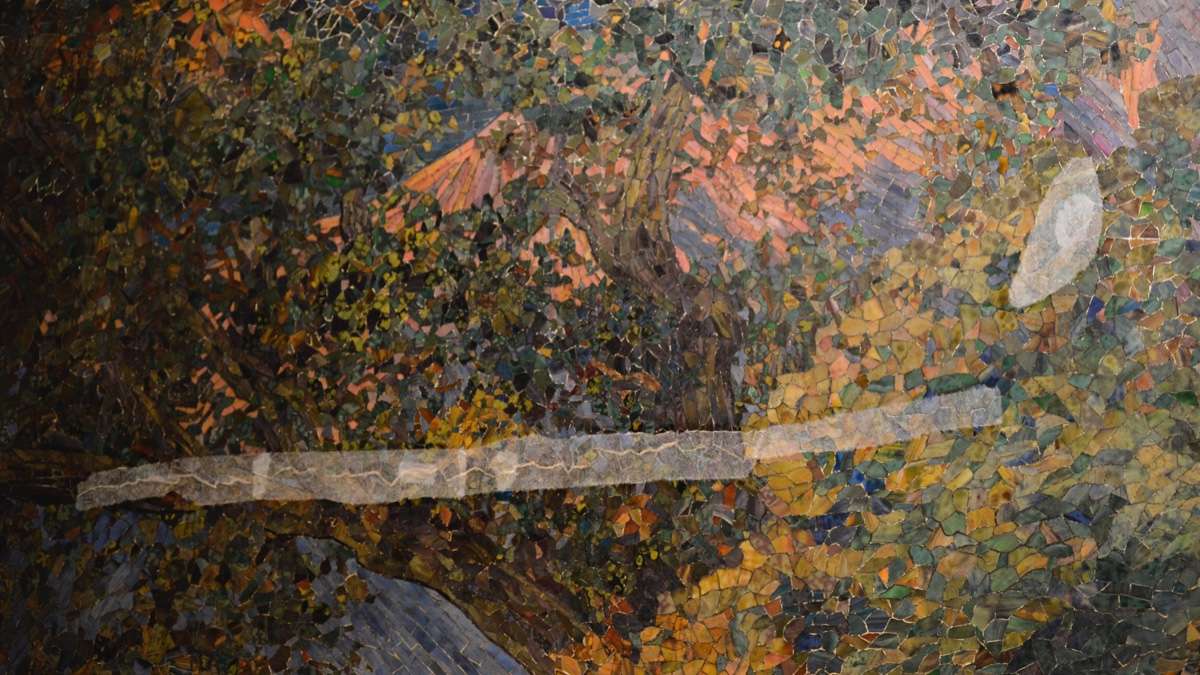

“Free Interpretation of Plant Forms” is a huge abstraction of a flower. Bertoia curved common copper tubing into giant undulating petals and coated the whole thing in bronze.

When demolition began on the Civic Center site in 2000, the four tons of copper and bronze was spirited away to a secret location: the parking lot of a police maintenance garage in North Philadelphia. A wooden shed was custom built to hide it from view. Even people working in the adjacent garage didn’t know the sculpture was there.

Margot Berg of the city’s office of arts and culture wanted to keep the sculpture safe because, literally, they don’t make ’em like that anymore.

“It’s difficult for Philadelphia to create new fountains,” said Berg. “It’s hard to maintain fountains in city parks. And just the size of it, where would we site it? It was a difficult thing to find a home for.”

According to Berg, the Bertoia fountain was the last sculptural fountain commissioned through the city’s One Percent for Art program.

She found a partner in the Woodmere Museum, housed in a 19th century mansion nestled between Fairmount Park and the Morris Arboretum. The fountain now sits on an expansive lawn ringed by trees.

The fountain’s natural shape is a natural fit, said William Valerio, museum director.

“Woodmere was founded by Charles Knox Smith who believed — in the late 19th century — that art and nature is a path to God,” said Valerio. “We might not use those words today, but it’s basically right: art is a spiritual experience and nature is a spiritual experience. Bringing them together can do something profound for the soul.”

The original location of the fountain — in a windswept concrete pool surrounded by masonry buildings — in some ways was not ideal. At the Civic Center, the sculpture was sprayed on all sides by high-pressure fountain jets.

“You had a beautiful, intimate piece of bronze and copper, but you couldn’t get to it,” said architect Matthew Baird, who designed the Woodmere’s master plan. “A 1960s modern fountain in a plaza pelted with water. It was not very accessible. Bertoia was not keen on that. He made a delicate plant form, and the last thing you do to a seedling is barrage it with a high-pressure hose.”

At Woodmere, water will emerge from the center of the flower form and flow out, eventually dripping into a gravel bed below the fountain. There is no pool — visitors will be able to walk up to the sculpture and touch it. The petal forms create adult-size niches.

While climbing on the sculpture will be forbidden, touching (and taking selfies) will not just be allowed but encouraged.

“I love the way it talks to the trees,” said Valerio, watching landscapers anchoring the fountain in its new home. “It’s a natural, organic form. In the green environment of Woodmere, it speaks to the elements of the sky, clouds, and trees.”

The sculpture has been anchored into place, but still needs to be cleaned and repaired by conservators. While in its storage shed, it became home to wasp nests and feral cats. The fountain is expected to become active in late fall.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.