Live-blog: Why safety messages win bike-ped campaigns

One takeaway from several of this week’s panels, here at the Pro-Walk, Pro-Bike, Pro-Place conference, is the key role negative messaging plays in bike and pedestrian advocacy campaigns.

It’s nice to think that positive visions bolstered by solid analysis and evidence will win the day, but talking up the economic benefits of traffic calming interventions like bike lanes and pedestrian plazas will only get advocates so far, said Jeff Miller, President and CEO of the Alliance for Biking and Walking, in a primer on winning biking and walking campaigns.

What really seems to move the politics is voters’ fears of injury and death, and politicians’ fears of being blamed for it. Miller has been at this for about 25 years, and he says almost every successful bike or pedestrian advocacy effort he’s seen has come out of something negative happening.

This Old City’s Geoff Thompson has noted that backlash from families in reaction to auto-related child deaths was one of the driving forces behind pedestrianization and traffic calming movements in Western European cities in the late 1970’s and early 80’s. (The city of Groningen, whose central district quadrant layout resembles Philadelphia’s, made it illegal to drive diagonally from one quadrant to another, which nudged cars to the periphery of the central district, making bicycling a substantially more convenient mode of travel.)

And it’s the same kind of safety message that’s winning out in New York City politics today. That is how advocates got Vision Zero – Mayor Bill de Blasio’s ambitious commitment to reducing traffic fatalities to zero – on the agenda in 2013 Mayoral primary.

Ryan Russo, the Deputy Commissioner of NYC DOT, recalled the successful efforts of groups like Transportation Alternatives to turn the “bikelash” around on traffic calming opponents using safety messages.

“We had an election in 2013. So all this was happening in the context of 7 years of aggressive street redesign and an election came where basically the question was: are we going to continue forward, or will there be a bit of a backlash or a retread to what we’ve been doing with the city streets?

Noah Budnik, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, was part of the team. I’m a transportation professional working at a city agency. We don’t have control over the overall political context of our city. And the 2013 election was a do-or-die moment for the direction that the city had been moving. We had moved aggressively on street redesign – there had been a backlash around that.

We had done the best we could of articulating the benefits of what we were doing, but the advocates and the families of victims of traffic fatalities organized in an amazing way to put this question to the candidates for Mayor: Are you committed to reducing traffic fatalities? And the ultimate winner of our election, Mayor de Blasio, really sensed that there was something underneath there.

As much of the bad press as we got for what we were doing with our streets, there was sort of a sense that our streets need to continue to evolve, that we need to change in other ways to get safer. As someone who is a practitioner, who’s subject to the political leadership and the political winds, it was a tremendous accomplishment and it really dictates what Vision Zero is in New York City right now.”

Vision Zero was a big winner in the latest round of TIGER grants announced this week. NYC is getting $25 million to implement safety interventions at 13 problem intersections.

Will street safety become an issue in the 2015 Philadelphia campaigns? It’s not something that’s really been on City Council’s radar, and doesn’t appear to be something that the broader electorate is really clamoring for outside our little corner of the Internet.

But that brings us to Alliance CEO Jeff Miller’s other point: correctly identifying the problem and the culprit have to come prior to developing an issue advocacy campaign.

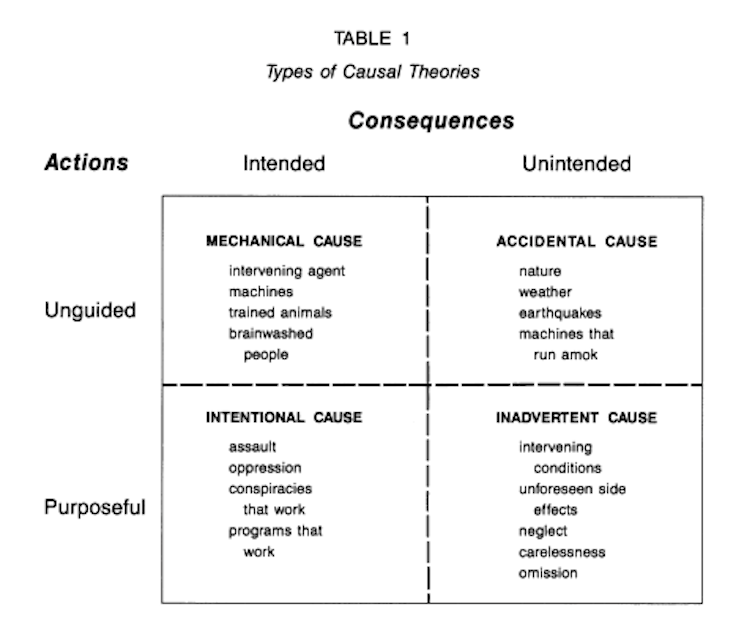

The difference between a problem and an issue is the presence of a causal story laying the blame on someone. Political scientist Deborah Stone has a useful table illustrating this in her paper “Causal Stories and the Formation of Policy Agendas”:

What happened in the 2013 NYC Mayoral campaign is that advocates changed the causal story by pushing the pedestrian collisions problem out of the Accidental Cause box in the upper right hand corner, out into the Inadvertent Cause and Mechanical Cause boxes. The story went from “collisions are just accidents with no interesting systemic cause” to “collisions are preventable tragedies that can be reduced with better streets policies.”

For now, in Philadelphia the pedestrian crash problem is still squarely situated in the Accidental Cause box for most voters, so City Council members aren’t really feeling political pressure to do something about it.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.