Less traffic, less risk: Zamar Jones’ neighbors pitch speed bumps as a violence deterrent

Following the fatal shooting of 7-year-old Zamar Jones, a West Philly block’s request for speed bumps is getting another look by the city.

Listen 2:26

Zamar Jones' neighbors placed candles, balloons, and roses in front of his home in early August. (Ximena Conde/WHYY)

Makeeba McNeely’s West Philadelphia block has a speed problem.

For years, the block co-captain and her neighbors on 200 N. Simpson Street have tried to slow down the flow of cars on their one-way street and installing speed limit reminders hasn’t helped.

“People just come racing through our block,” McNeely said.

The worst of the traffic, she said, comes during rush hour, but during the day young drivers take to the small street.

“They wanna come and take off at the top of our block, high speed, full force, and see if they can stop their car at the corner,” McNeely explained.

The block tried to petition the city for speed bumps in July, only to get a response that made the residents think they were ineligible. But following the fatal shooting of 7-year-old Zamar Jones, one of the block’s young residents, the request is getting another look by the city’s Streets Department.

The man who initiated the shootout that took Zamar’s life didn’t live on the block and started firing from his car, which he crashed while still on the block. The shooter then got out of the vehicle and continued to fire before stealing another car and driving off.

If an easy getaway is not guaranteed because of speed bumps, said McNeely, outsiders might reconsider barreling through.

“They’ll think a thousand times about coming down the block because you don’t want to tear their car up coming down the block over a speed bump and you try and pick up speed,” she said.

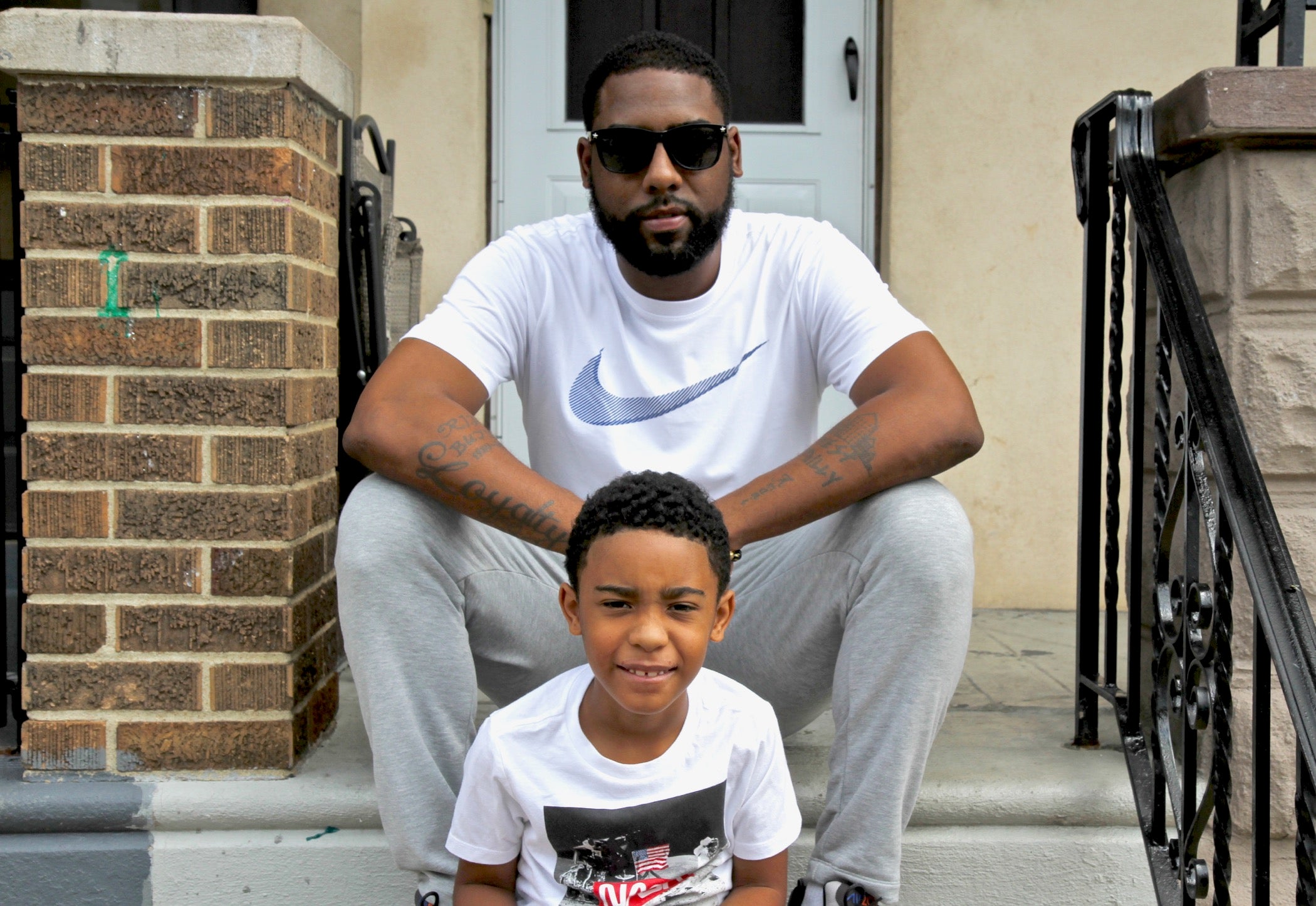

Jamar Young is a father on the block who campaigned for speed bumps in July. While they would mainly prevent speeding, they also present an opportunity to discourage outsiders from driving through and then hanging out on the block in the first place, he said. After Zamar’s tragic death, the possible solution feels ever more urgent.

“Less people, might equal less violence,” explained Young. “When you have something like a speed bump, and people know they can’t come down the block speeding and doing whatever, they won’t visit the block.”

Young said the speeding, the fights, the shooting that killed Zamar, all involved outsiders.

Most people on the block are “good people,” according to Young. They go to work, come home, and spend time with their loved ones.

It’s not the first time someone has pitched traffic calming tools as a way to deter crime: A Chicago alderman proposed spending $350,000 on speed bumps and cul de sacs in a high crime neighborhood — but there’s little evidence to back that claim.

Young’s “less people, might mean less violence” hypothesis has been tested in other ways, though — granted, long ago.

Several small neighborhoods have tested the relationship between crime and violence to traffic since the late 1970s and found some promising results.

Now it appears that Philadelphia, too, will be testing the theory.

Knowing how to ask

One of the reasons the block’s request for speed cushions — city officials don’t call them bumps — went nowhere in July had to with how they framed their request. The residents asked District Councilmember Curtis Jones’ office if they were eligible for the traffic-calming intervention given the facts of their street. Jones deferred to the Streets Department.

“The block does not meet the qualifications per our website/policy,” read the one-line email response from the Streets Department, which made the dads feel they’d reached the end of their experiment.

It turns out, 200 N. Simpson Street still does not meet speed cushion qualifications, but those qualifications are only a portion of what the city’s Streets Department considers when making a decision to install the raised asphalt.

Deputy Commissioner for Transportation Richard Montanez said the West Philly block is only 540 feet long and has a stop sign at the end of the block. To qualify for a cushion, the block would need to be 1,000 feet long with no other traffic calming measures, such as a stop sign.

Not meeting these requirements doesn’t prohibit the community from going through with the first step in requesting a cushion, which is to get a 12-week traffic study from the department.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

Residents and Jones should not have asked if they qualified for a speed cushion. They should have just asked for a traffic study, which is what Jones’ office did last week.

The results of that study could override any concerns about street length and existing traffic control measures.

“The Streets Department goes based on data,” Montanez said. “So if we see that there’s a crash problem or there’s a speeding problem, we do try to address those issues.”

“Try” being the operative word. Even after a three-month study, residents could end up with nothing. The slow wheels of progress frustrate many.

“Just come do your job,” said an exasperated McNeely to the department. “That’s what you’re getting paid for.”

Should the study echo speeding complaints residents have made for years, there’s still one big step. At least 75% of residents have to sign a petition in favor of the measure, though it may be the easiest hurdle for the block to overcome.

Dayton’s traffic experiment

One of the best documented and more successful cases of fighting crime with a traffic intervention came out of the Five Oaks neighborhood in Dayton, Ohio, which raised almost $700,000 to close off 24 streets and 26 alleys to traffic in 1993.

The racially diverse neighborhood, according to a federal analysis written years later, experienced a rise in crime in the late 1980s and leading into the ’90s prompting drastic action.

“Not only was crime increasing at a maddening pace, but drug dealers, pimps, and prostitutes had brazenly taken over the streets,” wrote Oscar Newman.

Speeding cars and gun violence, he said, were also plaguing the mix of working-class homeowners and low-income renters.

When police increased their presence “every few months,” wrote Newman, the problems would temporality subside.

That all changed after the city installed iron gates cutting off traffic.

By the time the New York Times profiled the neighborhood in 1994, violent crime had plummeted by 50% and nonviolent crime had fallen by 24%.

Not everyone was happy with the gates. Those living on the remaining through streets complained about bumper to bumper traffic. But overall, the neighborhood bought into the planning process. Researchers said the strong sense of community paired with the maze created by the gates, made people committing crimes from outside the neighborhood stay out.

A smaller traffic experiment in Philly is only the first step

Back on 200 N. Simpson Street, neighbors are all in agreement that truly stopping gun violence will require addressing the root causes.

Residents like McNeely, a self-described “old-head,” try to mentor young people on the block. When McNeely’s not at work, she’s part of the handful of neighbors keeping their eyes peeled for troublemakers, and she helps the block captain with events like the back to school book bag giveaway they had last week.

Still, McNeely said the block desperately needs reinforcements.

“Now you gotta worry about your child going to school, COVID, you trying to get finance for your child to get a babysitter,” said McNeely of challenges families are facing this summer. “How your child going to eat and how you going to keep an eye on your child while you’re at work?”

Add to that this year’s grim violent statistics. Despite a drop in overall violent crime, police have recorded 270 homicides, including Zamar, and more than 1,200 shootings in the city – both a more than 30% increase from this time last year.

McNeely wants investment in free lunch programs, child care help for families, and jobs for young people, but she’ll take a speed cushion, too. As will neighbor Caesar Grant, though he doubts speed cushions can do more than slow cars down.

“These young kids out here are just angry, and these little things set them off, and they’ve got these guns – I don’t know where they’re getting them from – speed bumps got nothing to do with that,” Grant said. “If speed bumps could stop shootings, the whole city would have speed bumps.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.