Jarrett Walker’s philosophy of public transit as means to freedom

Philosophers have long struggled to make sense of human existence and the freedom (perhaps illusory) that it provides.

“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains,” wrote Rousseau, lamenting the shackles of modernity’s frenetic demands nearly 270 years ago.

“Man is condemned to be free,” argued Sartre, sounding bitter in 1948.

“Frequency is freedom,” said Jarrett Walker, earnestly in a philosophy lecture disguised as a talk on transit planning Monday night at PennDesign.

Walker, an aptly-named transportation consultant and unexpected holder of a Stanford PhD in humanities, explicated his human-focused way of seeing transit before a crowd of city planners, SEPTA staffers, PennDesign students and others predisposed to laugh heartily at lines like, “I’m as addicted to smartphones as the next guy—they have made us realize how boring it is to drive.”

Walker is the author of Human Transit, a transit planning treatise and blog of the same name, which both espouse framing discussions about bus routes and fare transfer policies in lofty concepts like “freedom” and “liberty”.

“We all have a sense about freedom and imprisonment—It’s about not being able to move,” began Walker. “We are all in a prison, physically speaking, where the walls are where we can get to in a reasonable amount of time.” The goal of transportation planning is to increase the abundance of access, argued Walker. Faintly echoing John Stuart Mill’s “Utilitarianism,” Walker advocated for creating transit systems that help as many people as possible reach as many destinations as possible, as quickly as possible, so that they have as many real choices and opportunities as possible. Or, in other words: transit as a means to freedom.

The idea throws the usual conception of public transportation on its head: Most riders are “captive” passengers constrained and resigned to a bus commute, compared to the “choice” riders who have better options. Frequently, increasing ridership is framed as increasing choice riders, but Walker challenges planners to focus on the dependent riders.

That is to say: Imagine what kind of service the dependent bus rider would want, and deliver that, rather than trying to dream up a service for the choice rider. Choice riders are the hypothetical people don’t ride now, and whom some planners try to build transit systems for. Walker advocated for planners to treat current riders the way some tech companies treat early adopters and beta testers.

Such unconventional takes on taking the bus have made Walker a rock star in the transit planning world, which is a roundabout way of saying he managed to fill around half of a large lecture hall. Speaking of roundabout ways, they are a pet peeve of Walker’s, who preaches on the power of linear transit routes and grid systems to improve services.

Walker simultaneously simplifies transit planning and elevates it. It’s all simple geometry for Walker – the shortest (and thus fastest) route between two points is a straight line, we only have so much space available for cars, and more vehicles per route means more frequency and more riders. And all of that means more human freedom, the simple liberty of movement.

“It may be my philosophical training: I start with skepticism,” said Walker, channeling his inner Karl Popper. “I start with what I know. That’s why I start with geometry—I’m sure about that, and in a way that I’m not sure with psychology or human behavior.”

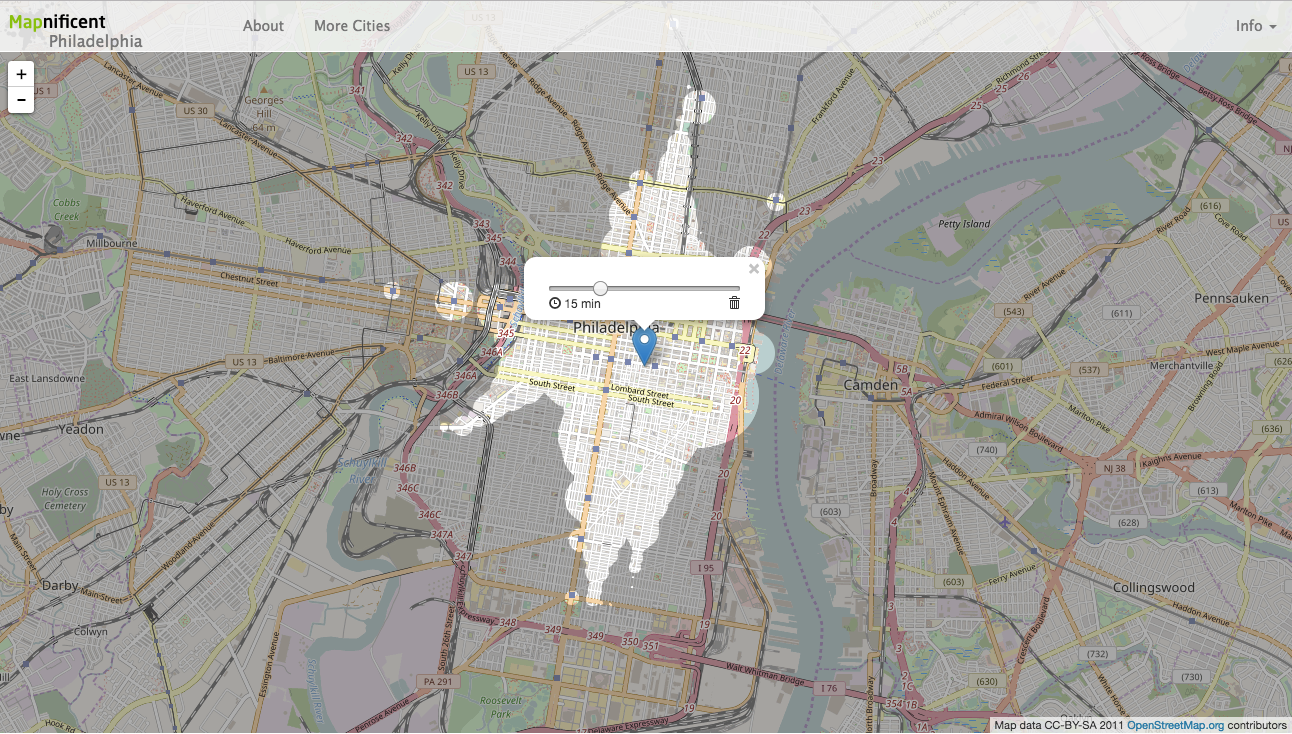

Consequently, Walker eschews ridership predictions as fool’s errands and a distraction to boot, favoring instead “isochrone” maps, which show how far a person can get via foot and mass transit in a certain amount of time, i.e. the limits of their practical freedom. “Does any ordinary person even care [about predictions]?” He asked rhetorically. “What if we talked about people’s liberty and freedom—things people actually care about?”

And yet, Walker knows how to drive up ridership, and is unflinching at what it takes to get there. In transit planning, the form of transit rarely matters, so buses, trolleys and trams can all work. To drive ridership, transit agencies should build networks that are well-connected with frequent service along dense neighborhoods with reasonable speed and reliability, says Walker. Focusing on those elements comes at a cost, though: coverage area.

Building a transit system with high ridership militates against broad coverage. It’s a tradeoff, says Walker, and where to balance the two is question for public officials to decide.

SEPTA has a tough challenge there: The authority could maximize riders by focusing on the urban core more, but at the cost of sacrificing coverage in the far-flung neighborhoods and suburbs. That might be a political non-starter for the agency, which relies on support from suburban lawmakers to secure funding in Harrisburg.

In Houston, elected officials supported a shift from broad coverage to heavier ridership, weathering a hailstorm of withering criticism in the process. Following Walker’s plans, they cut bus routes, straightened others, and relocated vehicles to provide more frequent service to more densely populated neighborhoods. Ridership boomed.

Walker delivered his remarks in between leading workshops at SEPTA and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. Monday afternoon, Walker led senior SEPTA officials in planning exercises aimed at rethinking bus services.

SEPTA may need all the help Walker can provide. Bus ridership (including trackless trolleys) dropped around 3 million last year, from 164.5 million in fiscal year 2015 to 161.7 million.

After his lecture, Walker politely refused to answer an audience member’s question on where Philadelphia sits on the ridership v. coverage scale, saying to laughs “I don’t do that off-the-cuff… for free.” But he may have inadvertently given away, gratis, two areas where SEPTA could make significant improvement immediately.

First, Walker emphasized the importance of maps—particularly frequency maps—in conveying the freedom offered by a transit system to its potential riders. Pointing to frequency maps like those in Pittsburgh, Walker said: “Philadelphia doesn’t have this and that’s why I didn’t ride any buses yesterday.” A great transit system is wasted if no one knows how to use it.

Second, Walker noted that straight routes aligned in grid systems maximize a rider’s abundance of access—the freedom he or she has to get to work, school, church, and play via transit in a reasonably short amount of time. Philadelphia’s streetscape lends itself to such a high-frequency grid system, but doesn’t quite get there because SEPTA doesn’t run enough east-west buses. “It’s also related to the fare system, which penalizes people for transferring,” said Walker, inspiring applause from the crowd.

SEPTA’s leadership has faced heaps of heated invective this past year, over Regional Rail defects, a strike, and a gas power plant—not to mention the usual grousing about the glacial pace of SEPTA Key implementation. Will it listen to the public transit philosopher and take on changes that will undoubtedly stir up some neighborhood opposition? Well, just maybe.

“Jarrett Walker produces an interesting, different way of looking at the normal paradigms,” said SEPTA’s Director of Strategic Planning, Byron Comati. “What he said to us was that there are some very obvious things we should be doing for how we deal with the future.”

“It’s also worth looking at that push and pull between frequency and coverage,” added Comati. “I think we got to have that dialogue.”

That may seem a bit pedestrian compared to Walker’s soaring rhetoric, but in SEPTA executive speak, that’s about as bold as one gets.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.