It’s not all about the face mask. How you wear it matters, too

Don’t go out without a mask, we’re urged. Our reporter tried making a few designs, and learned that how you treat your mask is important as well.

WHYY reporter Sabrina Emms, wearing a mask made from a T-shirt according to a design found in the New York Times. (Courtesy of Sabrina Emms)

We’re all being encouraged to wear face masks in public now to prevent the coronavirus from spreading. Everybody.

So, as a reporter and a concerned citizen, I tried my hand at making my own, experimenting with three patterns: a folded pattern; a simple four-tie pattern; and a slightly more complex pattern.

To make my mask more comfortable, I worked on the nose piece, which gave it a better fit, and also stopped it from pushing into the bridge of my nose. Touching even your masked face is a no-go, which means the mask must be fidget-proof.

“Huh?” responded one of my editors. She confessed she finds the idea of making a mask a little daunting, called herself a “mask moron,” and gave me permission to say that for the purposes of this story.

So here is my best advice for her and others like her. And because I’m not an expert, I talked to Amy Price, a senior research scientist, and Larry Chu, a professor of anesthesiology. They’re from the Stanford University School of Medicine and are the authors of a guide on masks.

First, a little background: The reason the N95 mask works so well and is so highly prized by health care workers right now is because it’s made from special materials.

“It’s made out of polystyrene, and it has what’s called a melt blown layer,” Chu said.

This melt blown layer is really important because it also carries a static charge.

“The static charge of the melt blown material attracts particles that come through with the electrical charge, and so therefore, it actually filters out smaller particles than you could with a regular cotton T-shirt or other materials,” said Chu, a physician who relies on N95s in his work.

It’s not the sort of material available to the typical consumer, but we all have something at home we can use to make a mask. A tightly woven fabric, 100% cotton, is a good start.

Hold your fabric up to the light. “If you can readily see holes, the weave is not tight enough,” Price said.

I tried a piece of T-shirt. The fabric looked like a grid full of tiny pinpricks of light, and it was stretchy. That’s also not good.

“You don’t want a stretchy fabric, because if this fabric is stretchy then the weave is loose and particles are going to go through,” Price said.

Some masks, like the origami mask designed by Philadelphia makerspace Nextfab, use vacuum cleaner bags. A pattern to make the mask is available for free if you sign in to Open Medical and join the mask making group. Vacuum bags can be hard to breath through, so they might not be a suitable material for all patterns.

Once you have the right fabric, you can start.

Some DIY options

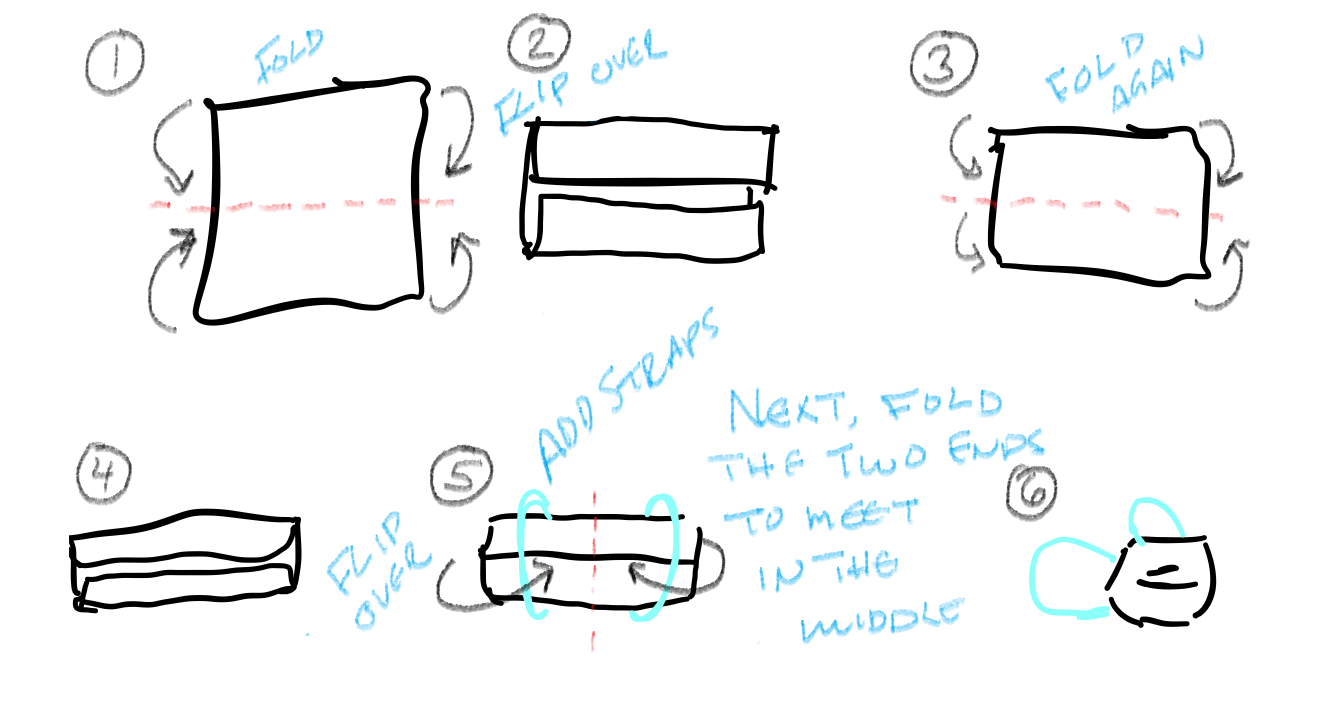

First, the folded pattern. This is the mask that Surgeon General Jerome Adams modeled making. It’s very easy.

I cut the back out of a T-shirt, which made a roughly 15-inch-by-15-inch square. That was slightly smaller than my pattern suggested. If you don’t have a ruler, you can line up two pieces of paper, one lengthwise, one widthwise, that will be 19 ½ inches, and you can estimate an inch shorter for your starting fabric.

With the fabric face down, fold the top and bottom into the midline, then flip and do the same thing again. Flip it back over, slide two elastic bands (for example, ponytail bands) each about a third of the way in, then fold the ends in, and off you go.

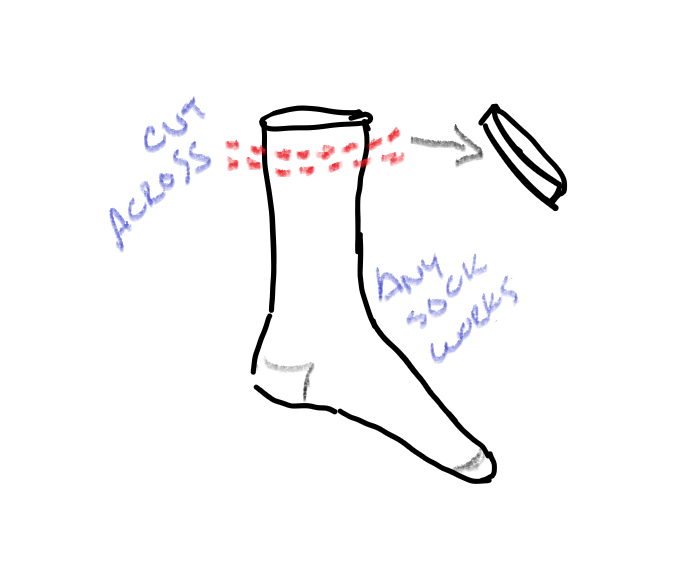

The folded T-shirt was way too thick and pressed against my face. Maybe with a bandana or thinner scarf this would be better. The tutorial I used suggested cutting up a sock into cross-sections to make elastic ties that go over your ears. That was an ingenious move, and worked really well. If you think of a sock as a tube that is closed at one end (the toe), you would cut perpendicular to the tube, so you make little rings.

Next, I tried the New York Times pattern. I have a sewing machine, so making this mask wasn’t very hard. Basically, you make a pleated square with a strap sewed into each of the four corners. I didn’t love the fit, and noticed a pretty big gap around my nose. I also kept tying the straps into my hair.

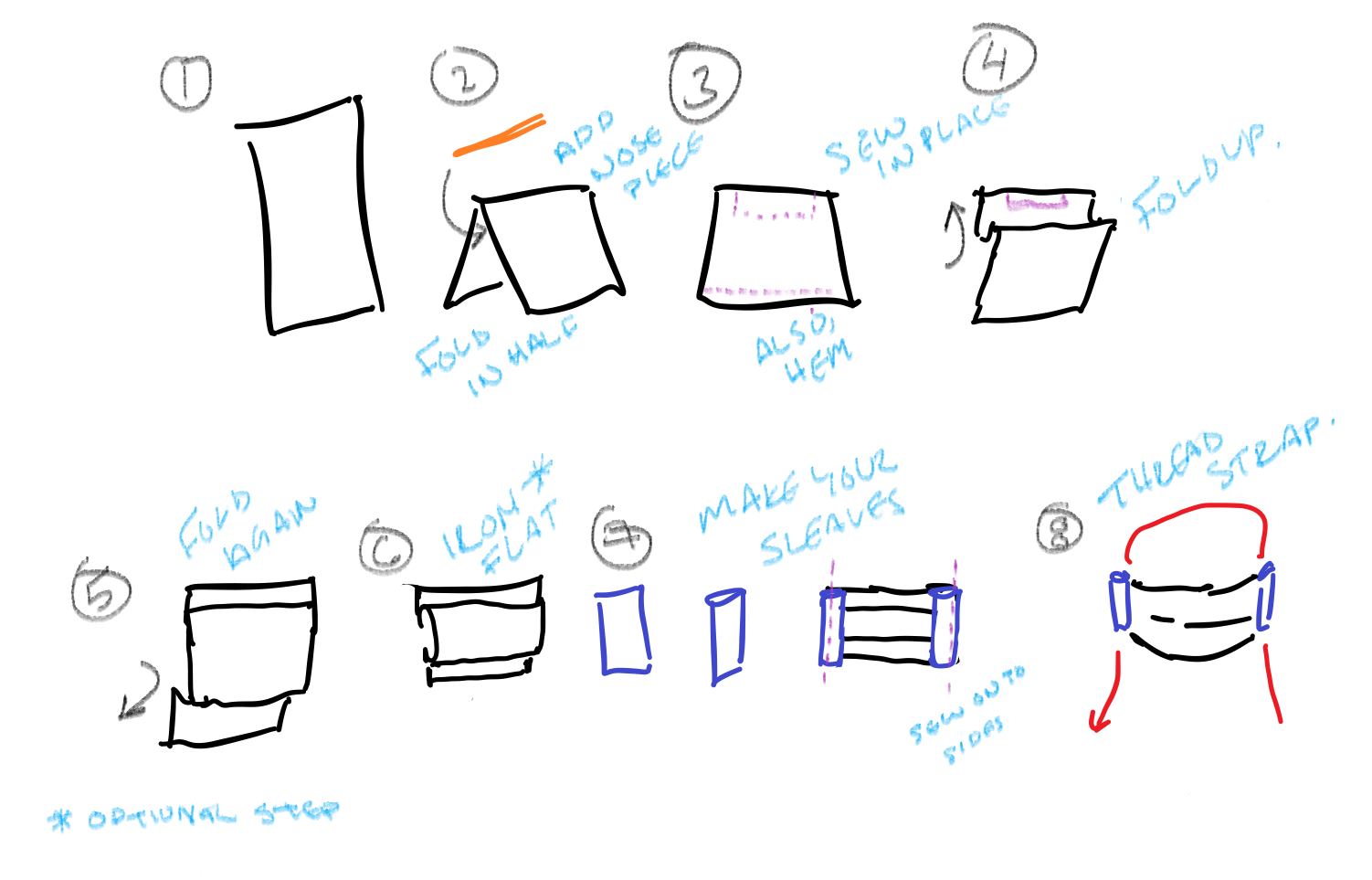

The third mask pattern was one my mum found through a Facebook friend of hers that’s making them. It included a nose piece and was my favorite.

Essentially, you start with a long piece of fabric, 8 ½ inches by 13 ½ inches, and fold it in half. You sandwich a piece of metal in the middle and sew around it. Then pleat the mask once in the middle, and add two little sleeves up the sides.

To pleat the mask, make a little fold about a third of the way down, and pull that fold up so it almost reaches the top of the mask. Then, do the same thing with the bottom. Next, I added my two little tubes of fabric to the sides. That’s where you’ll thread a single cord around the mask, that forms a loop for the back of your head, and two ties that tie behind your neck. I thought it was an excellent design.

Take a little piece of fabric, about two inches across and the same length as your pleated mask, and fold it so it’s still the same length as your mask, but narrower. Put it on top of the edge of your mask, on top of the pleats, then sew up the side. Repeat on the other side of the mask.

When you’re picking metal for the top, I switched the suggested bread tie out for a bent paper clip that I sleeved in a little piece of rubber tubing. The paper clip was more rigid, so I could get a really good fit to my nose, which I thought worked a little better. I was lucky to have some thin rubber tubing, actually a stretchy band from physical therapy. I imagine I could have wrapped the paper clip in tape, fabric, anything to cushion it, because the wire itself might not have made as nice a seal.

Making a homemade mask is significantly easier with a sewing machine — I made three pretty quickly. I also tried hand-sewing one, and that was also pretty successful. I am not a gifted hand sewer. It took me 35 minutes, and I poked myself twice. All in all, it was sort of a fun craft, and I felt pretty good about the end result.

Because masks need to be washed, we should all have several. If you make a couple, consider it good practice. The more I made, the faster and more confident I got. There are lots of other patterns available — and as long as it fits your face and you wear it, it doesn’t really matter how you make it.

Wear and care tips

When doctors wear N95s, they go through extensive fit testing.

“They make sure, through a variety of means, that the mask is actually sealing on our face as we move back and forth and bend over,” Chu said.

If you want to mask up like the experts, check the fit of your own mask and try to adjust to avoid any gaps. Even though putting on a mask seems like a piece of cake, even wearing an N95 without proper training might not be effective. Troubleshoot homemade masks and leave N95s to the professionals.

Of course, making a mask isn’t as useful as wearing one, and wearing it correctly.

“The best mask that you could take with you to the grocery store is the one that you have with you,” Chu said.

Don’t get hung up on fancy patterns or special material. Homemade masks stop droplets, so they contain any possible virus shedding if you are an asymptomatic carrier and you sneeze or cough. They also stop large droplets from getting in. Homemade masks are only as effective as your mask hygiene, and even the best one won’t catch everything.

Price explained that even long hair can be a problem. In the ideal world, you would wear a cap to keep it away from your face, but pulling it up in a braid or ponytail would also work.

“I want to make sure that my hands are absolutely clean before I touch a mask or before I touch anything,” Price said. “And then I only want to touch the straps of the mask and keep the rest of it clean.”

And once the mask is on, no more touching it.

Good mask hygiene continues even when you’ve taken your mask off.

“We’re very tactile as human beings. So we’ve had this strange thing on our face. The first thing it’s so normal to do is to [touch] our faces, right? Get rid of that itchy feeling, that foreign feeling,” said Price, and this is exactly what you shouldn’t do.

Wearing a mask is only one step.

“It’s training ourselves actually to keep our hands away from our faces,” she said.

“Used contaminated N95 respirators are considered biohazardous waste, and we wouldn’t want to bring that into our homes,” Chu said.

When you take your mask off, touch only the straps, it is now a possible biohazard.

“You could have some viral particles in the outside of your mask,” he said. “We know that these masks aren’t designed to, and don’t necessarily protect the wearer, against that mode of transmission. But large respiratory droplets might sit on the outside, for instance.”

When you take a mask off, “what you want to do is you want to have a Ziploc bag or maybe a little Tupperware pipe container where you can just pull it off,” Price said.

Dirty masks can be washed in the washing machine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but you could also wash them in hot soapy water outside, if you wanted to keep possible contaminants away from your home.

There’s a lot to adjust to, Chu said. Say you got a coffee and took your mask off and set it down to drink your coffee — that mask should probably not be put back on.

Price said research shows that help from our peers makes a big difference. We’re not all doctors or virology experts.

“We won’t have the same standards of cleanliness, and we’re going to slip up,” she said.

Chu warned, however, that wearing a mask might make us less careful, more likely to fall back into our old habits, even though they aren’t safe.

“We do have to keep in mind homemade masks are not N95 respirators,” he said.

Social distancing is still incredibly important. But so is compassion, Price said.

“So if I care about you as a human being, and as we care about each other as a society, then I think it’s our responsibility, not necessarily to wag the finger and to judge but to, as a collective, be a training ground and a support for each other while we learn this new way of living,” Price said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)