Is Uber really driving down DUIs? Let’s drill down to see what we can find

Last week, PlanPhilly ran an article suggesting that Uber and other would-be “transportation network companies” have reduced drunk driving in Philadelphia, based off of an analysis by Pittsburgh-based computer programmer (and rideshare advocate) Nate Good.

Good found that DUI arrests in Philadelphia have dropped about 11% (and 19% for those under 30) since Uber started operating in Philadelphia. This comes on the heels of a claim made by Uber in May that since the company’s entrance in Seattle, arrests for DUIs have decreased there by 10%. Uber did not respond to my request to discuss their study.

Given that Philadelphia has only enjoyed ride share for a little bit, I thought to look at the experience in a city where ride-sharing apps have been around longer: San Francisco, where Uber, Lyft and Sidecar all started.

Unfortunately, Wonkblog beat me to the punch: they found a similar small drop in DUI arrests since ridesharing started in the Bay Area. As they noted, though, there are more caveats in drawing a simple line between ridesharing and DUIs than there are potholes on Broad Street. Any number of factors can be driving this drop, including changes in driving habits and changes in law enforcement practices.

Most obviously, if people are drinking less, they’ll be drunk driving less, and visa versa. So I looked at public drunkenness arrests in San Francisco and Philadelphia and compared the DUI arrests as a measurable proxy for immoderate imbibition that is unconnected with how people get to and from the bar.

If the police blotter is full of arrests for being publically blotto, then folks are either drinking more or police are enforcing booze laws harder. Regardless, we should expect DUIs and public drunkenness to rise in tandem. And until Uber hit the streets, that was the case.

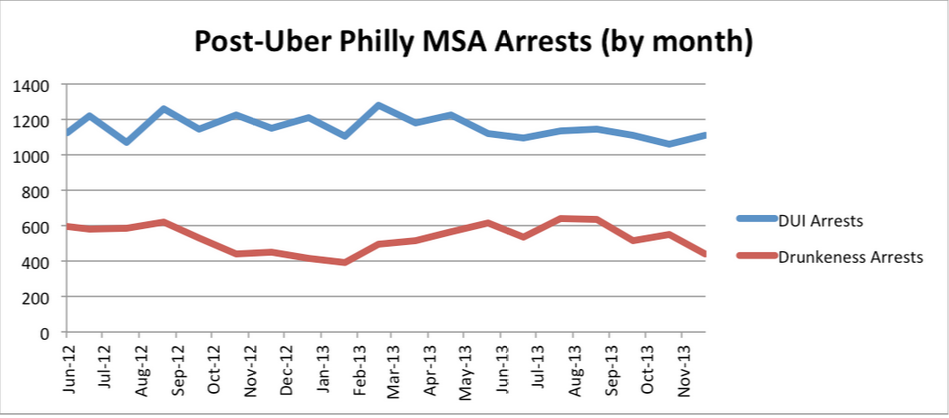

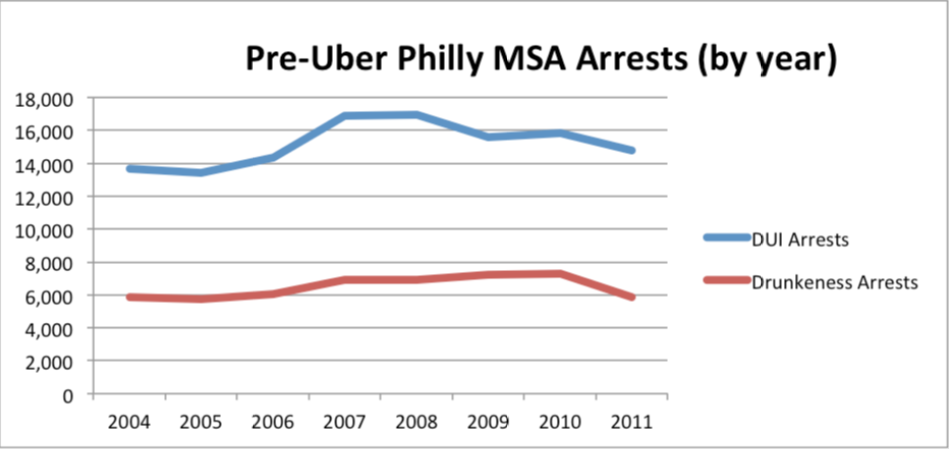

Before Uber was introduced in San Francisco and Philadelphia, arrests for DUIs and public drunkenness were highly correlated, with coefficients of .98 and .97 respectively. After Uber, the correlation disappears: .1 in San Fran, and -.05 in Philly. For those of us who weren’t Mathletes in high school, let me explain what this means: a coefficient of 1 means there is a perfect correlation – everytime A goes up, B also goes up (e.g. with every beer I drink, I think that I’m that much more attractive) and 0 means there is no correlation at all (e.g. with every beer I drink, how attractive I actually appear to others). So before Uber began in each city, arrests for drunk driving and drunk in public were very closely linked, but not so much after. This data makes Good’s analysis look even better.

I compiled DUI and drunkenness arrests before Uber started in San Francisco (2010) and Philadelphia (June 2012) and compared it with the monthly arrest data after Uber started in both cities. I used Uber as my before/after point because it was the first rideshare company in both. As Good and the Washington Post showed, DUIs are down in both Philadelphia and San Francisco since ridesharing was introduced – this data suggests that it’s not being of changes in law enforcement or the amount of drinking, generally.

The drops in DUI arrests in both San Francisco and Philadelphia are more likely the result of ridesharing than some other factor, such as changes in transportation preferences, drinking habits, or where people live.

Other fluctuations in our habits didn’t seem to have as large an impact on DUI rates. Americans are drinking about the same as they did in the past, but we’re venturing out to bars more than the past – as of 2011, we spent 40% of our booze money at bars and restaurants, compared to just 24% in 1982. More drinkers hitting the bar should mean more incidents of impaired drivers hitting the road (and objects on and around the road), not less. But drunk driving has been steadily declining nationwide over this same period of time (and thanks to improved car safety, the fatality rates have declined even faster).

In both San Francisco and Philadelphia, fewer commuters are driving than before, but this drop has been as steady as it’s been slow. In 2000, 83.3 percent of Philadelphians and 75.5 percent of San Franciscans drove to work; by 2012, those numbers dropped by 2 and 4.1 percent respectively, as more commuters chose public transit, bicycles and walking. These numbers track with a broad trend across the US: more and more people are living in cities, where driving is less necessary. In Philadelphia, we’ve been driving less, but I found no significant correlation between annual vehicle miles traveled in Philadelphia and Philadelphia’s DUI rates.

In fact, across the US, car ownership rates are down, as is the percentage of Americans with a driver’s license. We are driving less than before, and expecting DUI rates to drop too is perfectly intuitive. But the impact of the Great Recession is telling here: in 2008 and 2009, DUI arrests accelerated even as driving rates nosedived.

Like everyone else, I have my own caveats: I used data from data.sfgov.org, which apparently just logs arrests by the SFPD in the city of San Francisco (I say “apparently” because when I attempted to confirm this with the SFPD, they told me that they’d never heard of nor seen the data portal provided by the City of San Francisco).

For Philadelphia, I used the Uniform Crime Reporting System and looked at the Philadelphia metro area, which includes Bucks, Chester, Montgomery and Delaware counties. The Philadelphia MSA is much larger and significantly less urban than just the city of San Francisco, limiting the efficacy of comparisons between the two. I used commuter statistics as a proxy for travel patterns generally, which is a far from an ideal substitution. Moreover, correlation and causation are very much not the same. My analysis only lends further support to the argument that ridesharing helps reduce incidents of drunk driving – it doesn’t get close to proving it.

Still, it’s intuitive that giving folks who drink more transportation options helps keep them from driving. Regardless of how you feel about taxis or tippling, keeping frequent arm-benders from bending their cars around telephone poles is something to be encouraged.

Jim Saksa is a writer and attorney in Philadelphia. He’s written for Slate.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer and City Paper. Jim grew up on the Jersey Shore but loves Philly more – so much so he joined the board of Young Involved Philadelphia and leaves the City only begrudgingly. He tweets @Saksappeal and you can reach him at jimsaksa.tumblr.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.