Is mandatory inclusionary zoning the answer to Philly’s affordable housing question?

City Council’s attention of late has been focused on keeping rent and mortgages affordable for all in Philadelphia as steady, year-over-year population gains increase housing prices.

But the bills introduced to tweak existing anti-foreclosure programs, or establish new renter’s rights regulations, have so far been met with quick acquiesce or quiet grumbling.

The battle over Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez’s push for mandatory inclusionary zoning is shaping up to be something else entirely.

The bill would require developers building over ten units of market-rate housing to make at least ten percent of the project’s units affordable. A quarter of those would have to exist on the project site, while the other 75 percent could be built elsewhere or covered by making a payment into the city’s Housing Trust Fund (which goes towards the construction of subsidized housing). To help developers offset the costs of providing the affordable units, the legislation gives density, height, and floor-to-area ratio benefits to those required to participate.

Since the bill’s introduction in June, Quiñones-Sánchez convened a series of working groups to debate the finer points of the legislation. Over the last five months, this running discussion between politicians, developers, housing advocates, and experts has taken place with little fanfare.

But in recent weeks the debate has gone public. The Building Industry Association (BIA), a housing developer industry group, released a lengthy study that strenuously argued against the proposed policy. Then the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations (PACDC) issued a point-by-point rebuttal, disputing the BIA’s methodology and its findings.

After last Thursday’s City Council session, Quiñones-Sánchez said she isn’t shocked by the BIA’s opposition, noting that no industry group can be expected to quietly acquiesce to new mandatory regulations burdening their constituency. But the city’s existing inclusionary housing program, which is completely voluntary, hasn’t lived up to expectations: Only two developers have made use of it. Considering development-friendly city policies like the ten-year property tax abatement, she thinks it isn’t outrageous to ask for a little something in return.

“The city of Philadelphia has been very aggressive in supporting the redevelopment of Center City,” said Quiñones-Sánchez. “We are saying, to the market that we helped create, how will you help us create affordability and ensure mixed income neighborhoods? Particularly in the Center City core and as development spreads into the neighborhoods?”

The industry’s criticisms of Quiñones-Sánchez’s program are legion. Developers hate that it’s mandatory. They don’t think the zoning benefits are nearly generous enough. They rail against a provision that would make the requirement cover not just new construction, but projects to “substantially improve” existing structures, saying that owners would simply refuse to make upgrades. (The language in the bill applies to alterations that would cost over $7,000 and require a zoning permit, which means it would mostly apply when an owner was changing the number of units or the use of the building.)

Developers also believe the bill’s intended beneficiaries are nearly impossible for private companies to house while still making a profit. In Center City, the legislation would require pricing the units so they are affordable to households that make 50 percent of area median income (AMI), or $41,600; in the rest of the city they have to be priced for those at 30 percent of AMI, or $24,950. No other inclusionary zoning program in the nation attempts to reach residents with such low-incomes.

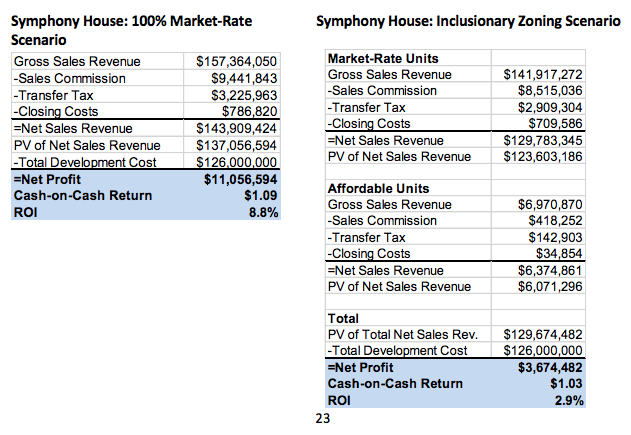

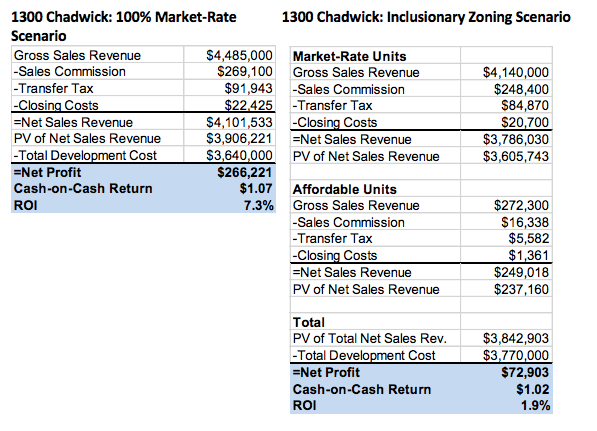

Most of all, BIA and its allies argue that the bill will bring housing development in Philadelphia to a shuddering halt. They say requiring private developers to build affordable housing means the financing of many projects simply won’t pencil out. And if new units aren’t being added to the market, that will mean the costs of existing housing will rise.

“[Our report] shows pretty clearly that the underlying economics of the legislation would be really devastating to the housing and real estate development industry in Philadelphia,” said Leo Addimando, BIA treasurer. “The basic math of adding 10 percent affordable, and getting back relatively ineffective zoning bonuses, it just doesn’t work. I think it would be very hard to argue that the bill in its current form would do anything but reduce jobs and reduce new housing.”

The bill’s supporters say BIA is crying wolf, a claim they buttress by noting the curious methodology in the industry group’s research paper against the policy.

In an attempt to deny that Philadelphia has an affordability problem, the study focuses on median house prices and median family income to craft a metric that supposedly shows why the bill is unnecessary. Median household income is the standard metric in these policy debates, but BIA used median family income numbers, which are higher than household incomes, thereby making Philadelphians appear better off on average than they really are. The study’s focus on median home sales may also create misleading impressions of affordability in a city where a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line and could never afford a downpayment.

But some economists do share the industry group’s concerns about the inclusionary zoning bill’s potentially dampening effect on housing construction, especially given the expansive nature of Quiñones-Sánchez’s bill and Philadelphia’s comparatively modest construction boom. Research shows that the results of inclusionary zoning programs on housing construction and prices are mixed and highly dependent on local conditions.

While it’s true that cities across the nation use inclusionary zoning, most of them are in some of the nation’s hottest real estate markets: New York City, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, and Washington D.C. and its wealthy suburb of Montgomery County, Maryland. Philadelphia would be among the first Rustbelt cities in America to establish such a policy. In its current form, it would be much more generous than most, covering broader range of projects and requiring more units built for poorer residents.

Asked about the effect of Quiñones-Sánchez’s legislation, economist Alan Mallach, who supports inclusionary zoning, said he believed it could certainly bring affordable units to Philadelphia’s hottest neighborhoods. But he acknowledged that this city is unlike many others that have adopted such practices; the majority of Philly’s neighborhoods — like the Far Northeast, Overbrook, or West Oak Lane — have stagnant housing markets without much new, market-rate construction.

“Clearly, in Philadelphia, you’re not going to be able to be as rigorous or tough as you could be in New York or San Francisco,” said Mallach, who is a senior fellow at the Center for Community Progress. “But if you come up with some decent cost offsets, and you keep [the requirement] at ten percent, I think you could probably make it work.”

INCLUSIONARY GROANING

Others are less sanguine. Joe Cortright, an economist at City Observatory, has long argued that inclusionary zoning is an underwhelming policy that produces few meaningful benefits. Like BIA, Cortright believes that inclusionary zoning can discourage developers from building abundant market-rate housing. In turn, that keeps supply flat as demand rises, leading to higher prices for older units that would otherwise naturally decline in price as they age, thereby offering affordable, or at least less-expensive, housing.

“I think that inclusionary zoning is, at its heart, a very counterproductive policy,” said Cortright, a former Brookings Institution scholar. “At a time when the private sector is willing to respond to demand, you’re essentially creating disincentives for them to invest in additional housing stock. If you don’t build enough housing at the high end of the market, it isn’t as though all those households who would live in that housing just go away.”

Cortright and other inclusionary-zoning critics also argue that the policy simply doesn’t provide that much good for all the potential downsides. One chart prepared by the New York City Planning Commission showed that mandatory inclusionary-zoning programs in San Francisco only created 1,560 units between 2002 and mid-2014. That made San Francisco’s program one of the most productive in the nation, but those 1,560 units over a twelve year period are but a drop in the bucket for a city that added 27,734 units total over the same period, and which saw rents double and home prices go up 40 percent between 2006 and 2014.

Even proponents of Quiñones-Sánchez’s bill admit it won’t create a huge number of new affordable units. An analysis based on Department of Licenses and Inspections data, and cited by PACDC, suggests that the bill would have only created 633 affordable apartments if it had been law between January 2014 and August 2017.

That figure doesn’t even get close to replacing the 23,000 affordable homes the city lost between 2000 and 2014. It would reach very few of the 60,000 low-income households in Philadelphia that spend over half their earnings on rent every month, which is considered a precariously high level that puts those families at greater risk of eviction. The waiting list for a public housing unit in the city is over 40,000 long.

For the BIA and experts like Cortright, that’s another strike against inclusionary housing: Why imperil housing construction, and Philadelphia’s modest recovery, for just a handful of units?

“Absolutely, mixed income housing programs are not going to solve our housing problems,” said Beth McConnell, PACDC policy director. “But these are units being created that wouldn’t be created otherwise, and without additional public subsidy. This small number of units will be meaningful to the people who get access to them.”

BIA’s Addimando downplayed the idea, advanced in their report, that his organization wants to dispute the idea that there is an affordability crisis.

BIA opposes almost every aspect of the current bill, but Addimando says the group and its members are open to addressing the issue. They just think there are other, better ways to do so.

“We aren’t arguing that hundreds of thousands of people in this city aren’t in desperate need of quality affordable housing,” said Addimando. “BIA is at the table. We’re not denying that something needs to be done. But this is not the right policy solution.”

Quiñones-Sánchez says that critiques of the inclusionary zoning requirements for retrofitted buildings hold weight. She also agrees that there are legitimate concerns over the city’s relatively high cost of construction and mandatory parking requirements. But she also feels that the bill’s passage is secure, no matter how much BIA fights the bill.

“Some of the BIA’s feedback has been very, very productive,” said Quiñones-Sánchez. “Some issues they’ve brought up are legitimate and we will address them in whatever amendments we make. They remain at the table despite their opposition because they know we’re going to pass a bill by the end of the year.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.