In the first language of our heart: Immigrants keeping the Catholic faith alive in Philadelphia

ListenIn many ways, St. Thomas Aquinas is a church like any other. Founded over 100 years ago, it was first predominantly Irish, then predominantly Italian, always matching the ethnic makeup of its corner in South Philadelphia.

It’s a history many Philly churches share, parishes like St. Donato, St. Laurentius, and St. Anthony of Padua.

Those three — and many others like them — are now gone, their doors shuttered and congregations shunted into merged parishes.

Meanwhile, St. Thomas Aquinas is going strong.

About 400 parishioners gathered there on recent Saturday evening. The vigil Mass is led by Monsignor Hugh Shields, a gray-haired, lifelong Philadelphian and son of Irish immigrants whose ruddy cheeks seem permanently arched upwards in a smile.

That grin only seems to fade during the solemnity of prayer, as it does when Shields leads the congregation in the Lord’s Prayer:

“Padre nuestro que estás en los cielos…”

At St. Thomas Aquinas, the most popular Mass is in Spanish. Monsignor Shields also presides over three Masses in English, which each attract around 100 parishioners.

Not bad, considering some churches struggle to get more than a few dozen through their doors. But it’s not good enough to be the second highest attendance at St. Thomas Aquinas… or even third.

Father Joe Dinh Huynh celebrates the second most popular Mass most weeks. This week, a substitute leads around 300 parishioners in prayer.

And third? That’s usually led by Father Didik Setiyawan. It’s in Indonesian.

St. Thomas Aquinas is a “shared” parish, and has been since the late ’80s. That’s when Father Arthur Taraborelli was appointed pastor. Growing up, Taraborelli attended St. Thomas Aquinas himself, just another Italian kid in a South Philly parish full of them. But by the time he became the church’s pastor, the neighborhood looked and sounded radically different. The Italians and Irish working-class families had largely left for the suburbs, replaced by African-Americans and, increasingly, recent immigrants from Southeast Asia.

Taraborelli embraced the diversity around him, petitioning the Archdiocese for a Vietnamese priest as his assistant. Father Joseph Dinh C. Huynh soon arrived, and with him, liturgical services in Vietnamese.

Kenn Bui left, and Paully Luong present offerings to Father Joseph Dinh during the Vietnamese Mass. (Jonathan Wilson/for NewsWorks)

Father Taraborelli passed away in 2006, but his parish’s dedication to multicultural ministry stayed. As Hispanic and Indonesian immigrants moved to the area, attracted by the same affordable housing and access to jobs as previous generations of migrants, St. Thomas Aquinas added masses in those languages, too.

“We pray best in the first language of our heart,” said Shields, who heads the parish.

It’s harder to “feel that intimacy that is meant to be felt as we pray to a supreme being,” he added, when you’re struggling just to understand what prayer’s being said.

Despite the different languages, the parishioners feel a sense of shared community.

“St. Thomas Aquinas, for me and my family, is like home,” said Oscar Lopez. Lopez moved here with his wife from Guatemala in 2003.

“We get together with the other groups and even though our English is not good and the accent is not good, with the other communities I feel like home ’cause they are in the same situation,” Lopez says.

Lopez is undocumented, but his son, who is “a really good student” at St. Thomas Aquinas’ parochial school, was born in America. He’s been able to visit his grandparents in Guatemala, whom Lopez and his wife haven’t seen in 12 years.

Lopez says he came here for a better life. He works in construction and pays his taxes, hoping to become a U.S. citizen one day.

“I want to do things right and get everything on book, but it’s just…It’s just like a door that I can’t open just because of my status.”

It’s a status Lopez shares with many of the Latino and Indonesian parishioners at St. Thomas Aquinas.

Most Vietnamese immigrants in the U.S. were granted asylum following the Vietnam War.

But the U.S. didn’t feel the same sense of moral culpability when ethnic Chinese and Christian Indonesians faced persecution in the 1990s. Many Indonesians fled to America and never returned, opting to overstay temporary visas and risk deportation rather than face certain oppression back home.

Even with the proper paperwork in place, life as an immigrant, or just life in this corner of Point Breeze, can be hard. That struggle is “something we share,” Carmen Maria said in Spanish.

The deportation fears aren’t as acute as they once were. President Barak Obama’s executive order on Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals in 2012 eased some concerns. The administration also eased enforcement and removal policies, meaning undocumented immigrants who stay out of serious criminal trouble are unlikely to face deportation.

But the Obama Administration’s exercise of executive discretion on immigration enforcement has been challenged in federal court. If that lawsuit succeeds, or if one of the populist, anti-immigrant presidential candidates wins the 2016 election, the relative sense of comfort will vanish.

Even today, the St. Thomas community worries that contact with the police might end in deportation proceedings, said Bethany Welch, director of the Aquinas Center. The Aquinas Center, housed in a former convent next to the church, serves pastoral needs of the community beyond the sacraments, offering supportive services like ESL classes and counseling.

Monsignor Hugh Shields and Aquinas Center Director Bethany Welch stand outside of St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church. (Jonathan Wilson/for NewsWorks)

Welch recalls handing out small toy prizes to some kids attending summer camp a year ago. She handed one seven-year-old a little toy police car, “and he literally in front of me broke down in tears.”

At first, Welch thought it was just a case of a child throwing a tantrum. But then, she said, the little boy explained why he was upset: They took my dad in a car. And that’s the last time I saw him.

“For him, that’s a symbol of separation and anxiety,” explained Welch.

Welch and Shields have become advocates for immigration reform, like many others in the Catholic Church.

According to a 2014 Pew survey, 77 percent of Catholics support allowing undocumented immigrants to stay legally in the U.S. provided they meet certain requirements. Even looking only at non-Hispanic, white Catholics, support for a path to permanent residency or citizenship was 70 percent.

The Church’s position on immigration was established by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in a 2003 pastoral letter entitled: “Strangers No Longer: Together on the Journey of Hope.”

In the letter, the USCCB emphasized the moral obligation of wealthier nations to accommodate migration flows, writing that the impoverished have a right to emigrate to find employment.

It’s an point Pope Francis has also made: “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph knew what it meant to leave their own country and become migrants: threatened by Herod’s lust for power, they were forced to take flight and seek refuge in Egypt.”

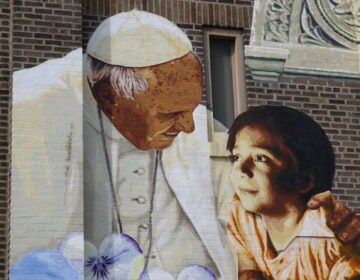

Himself the child of immigrants who fled poverty and the rise of fascism in Italy, Pope Francis’ first trip outside the Vatican as Vicar of the Holy See was in Lampedusa, a small Mediterranean island about 90 miles off the cost of Tunisia that has become an epicenter for refugees fleeing conflicts across North Africa and the Middle East. Thousands have arrived there by boat, and thousands more have drowned trying to get there.

Francis has been depicted as the smiling pope, the self-effacing pope, the forgiving pope. But on immigration, he’s the indignant pope, the demanding pope, the imploring pope. At Lampedusa, Francis recalled God’s question to Cain after he killed his brother Abel, saying the blood of refugees stains the hands of the indifferent.

“‘Where is your brother?’ His blood cries out to me, says the Lord. This is not a question directed to others; it is a question directed to me, to you, to each of us. These brothers and sisters of ours were trying to escape difficult situations to find some serenity and peace; they were looking for a better place for themselves and their families, but instead they found death.”

Some hope Pope Francis will echo these same themes when he comes to Philadelphia. Francis will give a speech Saturday afternoon on immigration in front of Independence Hall.

This pontiff’s appeal stems largely from his lived faith – the humility he demonstrates embracing the poor and marginalized. It is as St. James wrote in his epistle: “Faith without works is dead.”

But the same could be said of the U.S. Catholic Church without immigrants. As much as the USCCB’s position on immigration is rooted in Catholic social thought, it is also a statistical fact that the U.S. Church would be devastated without them.

According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University, the percentage of foreign-born Catholics among all U.S. Catholics has gone from 10 percent in 1975 to 32 percent in 2014, with 21.5 million immigrant Catholics out of 66.6 million overall. That same year, though, the CARA surveys also counted 28.9 million former Catholics.

If it weren’t for immigrants, the population of American Catholics would be shrinking, and quickly, instead of growing. That’s true for Philadelphia, too: it has been foreign-born immigrants, perhaps more so than any other demographic, that have been responsible for growing the city’s population after decades of decline.

While the Archdiocese of Philadelphia doesn’t track immigration statistics for its parishioners, the experience here is no different than the rest of the U.S., says Father Bruce Lewandowski, who heads the Office for Cultural Ministries.

“Nationally, the Catholic population has stayed steady because of immigration,” he says. “We have to accept that’s our [the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s] reality, too.”

It’s a reality Sam Paranzino readily accepts. Paranzino is straight out of central casting for “Italian Catholic from South Philly”. Interviewed on his front porch, Parazino wears a t–shirt that says “Italia” across his broad chest. Swallowing vowels galore, the garrulous Mummer can talk animatedly, and endlessly, about serving as an altar boy captain at St. Thomas Aquinas, the weekends down the shore, his work with the Men of Malvern… anything, really.

Paranzino watched the church decline along with the neighborhood around it as many of the white, working-class families left. But he’s also seen St. Thomas grow again, thanks to the Vietnamese, Indonesian, Filipino and Latino families. “I see that church growing even beyond my expectations, I really do,” he said, “because they opened the boundaries. And once you open the boundaries, you’re going to see a lot more people coming in.”

A view from the choir loft of St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church (Jonathan Wilson/for NewsWorks)

Paranzino said he welcomes all the new nationalities, and occasionally attends some of the non-English masses, despite not knowing the language; the liturgy doesn’t change much. And like most of them, Paranzino is excited for the papal visit.

So too is Oscar Lopez, the young father from Guatemala. Lopez was the third person to sign up for St. Thomas’s allotment of tickets to hear Pope Francis at Independence Hall, when the pontiff will discuss immigration. Lopez has high hopes for the speech.

“Reform… that’s what we want and we hope that we can — someday — we can get something so that I can….” Lopez trails off and gathers his words. “So we, as a family, we can go back and visit our parents.”

So many in Philadelphia are pinning their hopes on Pope Francis, praying he can inspire the nation to finally tackle immigration reform.

“We have a tremendous amount of people flying below the radar screen in fear,” says Fr. Shields, the pastor at St. Thomas Aquinas. “That’s not what our country was founded for, that’s not what our faith says. Jesus says, ‘Be not afraid, do not fear.’ And we, as a country, I think, we have an obligation to our Founding Father.”

But even if Pope Francis says and does what they all want His Holiness to say, will it matter? The UN Refugee Agency counts 59.5 million refugees displaced by conflict worldwide, and Pope Francis has excoriated the governments of Europe for turning a blind eye to their suffering.

And yet, in Hungary, a predominantly Catholic nation, the borders have been shut, despite pleas from the pontiff. Austria, 73 percent Catholic, has followed suit.

Shields still believes Pope Francis will bring a message to Americans will be forced to hear, “even if we want to close our ears.”

“He’s bringing the cries of the poor to us,” said Shields. “He’s asking us to help others who are our brothers and sisters.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.