In South Philadelphia, a public school revival pushes against its limits

Listen

Students arrive at Andrew Jackson Elementary School for the start of the school day. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

On a rain-drenched Friday in late March, about 75 people pack into a cinderblock room at South Philadelphia’s Hawthorne Recreation Center just north of Washington Avenue.

The rhythmic blare from a nearby Mexican dance class bleeds through the walls. Along the room’s perimeter, women saddled with Babybjörns rock infants to sleep.

If ever a scene captured the new face of South Philadelphia, this might be it: A room full of young, mostly white professionals chatting over the muffled hum of Latin folk music.

The topic this evening is overcrowding at nearby Andrew Jackson School, a K-8 school about five blocks south that serves parts of Bella Vista and East Passyunk. Before the meeting starts, I sidled up to Stephen Dunne, a lawyer who recently bought a house across the street from the school.

“Oh it’s an incredible turnout,” he said with an eager smile. “You’d think this was a private school. It’s a public school in Philadelphia.”

Dunne and his wife picked their house because of its proximity to Jackson, one of four or five public elementary schools they considered viable. That dynamic isn’t new — there’s long been a select band of schools deemed good enough by the city’s middle class.

What is new is Jackson’s presence among that group.

Less than a decade ago, Jackson sat half empty — just another three-story reminder of the city’s crumbling public school system. Today it can barely contain the 567 children scurrying through its corridors.

In fact, all over South Philadelphia — from Front Street to Broad Street, from South Street to Snyder Avenue — public school enrollments are swelling. The extent and consistency of the trend reaffirms that the urban revival started in Center City a few decades ago has advanced well past downtown. Jackson’s overcrowding problem is, at least in part, the latest high-tide mark from a wave that seems to advance farther south every year.

But the Jackson story is not merely the story of middle-class return. It is also the tale of an immigrant influx that has breathed life into so many corners of the city. It is the story of a cook from Puebla, a first-grader from Mexico City, a stay-at-home mom from Acapulco.

At Jackson, the twin trends of gentrification and immigration have collided in happy harmony. And they have left the School District of Philadelphia with a rare and enviable problem: After years of managing decline, the district must consider how it will manage real and sustained pockets of growth. Moreover, it must consider how to manage that growth without alienating the newcomers who have fueled the resurgence or marginalizing those who kept so many of these schools alive.

A tale of two tours

Principal Lisa Kaplan can give visitors to Jackson one of two tours.

The first is virtual. It lives in a PowerPoint presentation on Kaplan’s desktop computer. As far as I know, it doesn’t have a name, but it could reasonably be titled, “The Crap I Inherited.”

On one slide, there’s a drab-looking gym with moldy curtains. Another shows a cracked slab of concrete masquerading as a playground.

“Water leaks throughout. Dull and dismal,” Kaplan said as she clicks through the slides.

This is what Jackson looked like seven short years ago when Kaplan arrived as principal.

“When I got here, nobody would go to Jackson,” Kaplan said. “It was sort of like a dumping ground kind of school. When you would say the word ‘Jackson,’ people would go, ‘Oh, Jackson. Blech. Never send my kid.'”

The second tour happens every Wednesday and consists of a guided walk through present-day Jackson. It’s a tradition of Kaplan’s to open the school up once a week. Everyone is invited, and typically about four folks show up.

On this tour, Kaplan shows off a school far different from the one on her desktop. She walks people through a refurbished multi-purpose room with new sound-proofing panels courtesy of a parent fundraiser; the music room with its rows of glistening instruments; the rooftop garden; the Keith Haring-style mosaic made of rescued bottle caps; and the massive new play dome.

“I think it can hold 35 kids,” Kaplan said, adding that only one school in the district has a bigger jungle gym.

Andrew Jackson Elementary School Principal Lisa Kaplan. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Andrew Jackson Elementary School Principal Lisa Kaplan. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

When Kaplan arrived here in the 2009-10 school year, she wrote down everything she wanted to do or add — the type of pie-in-the-sky wish list that no urban principal realistically expects to fulfill.

In seven years, she’s checked off every single item.

“It’s like a dream,” said Kaplan, a 37-year veteran of the district, fighting back tears. “Like, I can’t believe the things that have happened here. And it makes me so happy.”

About everyone puts Kaplan at the center of Jackson’s turnaround. She’s coaxed local companies into donating tens of thousands of dollars and spearheaded the formation of a parent fundraising group called Friends of Jackson, which has poured thousands more into the school.

She is, as one parent tells me, a difficult person to say no to.

There have, however, been resources at Kaplan’s fingertips her predecessors simply didn’t have.

The twin forces of immigration and gentrification

Much of the money to build Jackson’s new playground came from a local developer who converted a former Catholic school down the street into luxury apartments. A parent with connections to Ballinger convinced the architecture firm to donate a sparkling countertop for the main office. Behind so many of the physical improvements, there are hints of the new wealth that has flooded this neighborhood in recent years.

“It’s very much a story, in some ways, of gentrification in the neighborhood,” says Melissa Wilde, a sociologist and founder of Friends of Jackson who moved to the neighborhood in 2006. “A developer that wanted to build luxury apartments wanted to build a playground.”

When I mention this to Kaplan she bristles a bit — and perhaps for good reason. Jackson is no country club. About 64 percent of the students receive government assistance, and there is a near-constant inflow of newcomers from abroad.

“We’re in a very interesting dichotomy, because we have college professors and doctors,” said Kaplan. “But last week I got six kids in the building — three from El Salvador, one from China, and two from Syria.”

The rush of middle-class urbanites to South Philadelphia has certainly allowed Jackson to add an abundance of bells and whistles. And there’s little doubt that Jackson has earned the elusive and coveted “good school” label among those with the income and savvy to choose.

The school’s white population has more than tripled in the last seven years. Wilde believes the school has developed an almost irrational amount of momentum among the neighborhood’s professional class — partly due to the headline-grabbing popularity of its music program.

“My 5-year-old is going to go to a very different school than my 10-year-old did,” Wilde says. “The middle-class parents are opting in. Where they used to almost all opt out.”

But the middle-class embrace of Jackson doesn’t totally explain its growth, or even come close.

!function(e,t,s,i){var n=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”),d=o[0],r=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(i)&&(i=r+i),window[n]&&window[n].initialized)window[n].process&&window[n].process();else if(!e.getElementById(s)){var a=e.createElement(“script”);a.async=1,a.id=s,a.src=i,d.parentNode.insertBefore(a,d)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”,”//e.infogr.am/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);Percentage of total population by raceCreate pie charts

Between 2000 and 2010, the five Census tracts that intersect with Jackson’s feeder area (also known as a “catchment”) grew 12.8 percent — or about 20 times faster than the city as a whole. Non-white Hispanics and Asians were the fastest growing ethnic groups. Today there are 29 national flags lining Jackson’s hallways, one for each home country represented in the school’s nine grades. Since 2009-10, the school’s Hispanic population has doubled.

| Jackson Enrollment | African American | White | Hispanic | Asian | Total |

| 2009-10 | 109 (36%) | 38 (12%) | 91 (30%) | 56 (18%) | 305 |

| 2016-17 | 131 (23%) | 129 (23%) | 188 (33%) | 64 (11%) | 567 |

Sergio Ruiz, a chef from Puebla, Mexico, said Jackson has a welcoming reputation among the area’s Latino immigrants.

The school’s leaders “take care of everyone,” he said. It is a “happy” and “comfortable” place in a society that can feel hostile.

Ana Canchola arrived at Jackson in 2007 as a shy first-grader with almost no understanding of English. The native of Mexico City found her social and academic footing through the school’s ballyhooed music program.

“The band is like my second home there,” she said.

Canchola now attends Girard Academic Music Program, one of the city’s top magnet schools, and plans someday to become an immigration lawyer.

A plurality of Jackson’s students are Hispanic, but there is no majority racial group at the school. That’s fairly rare, and it makes Jackson one of the most ethnically diverse schools in Philadelphia.

A popularity surge

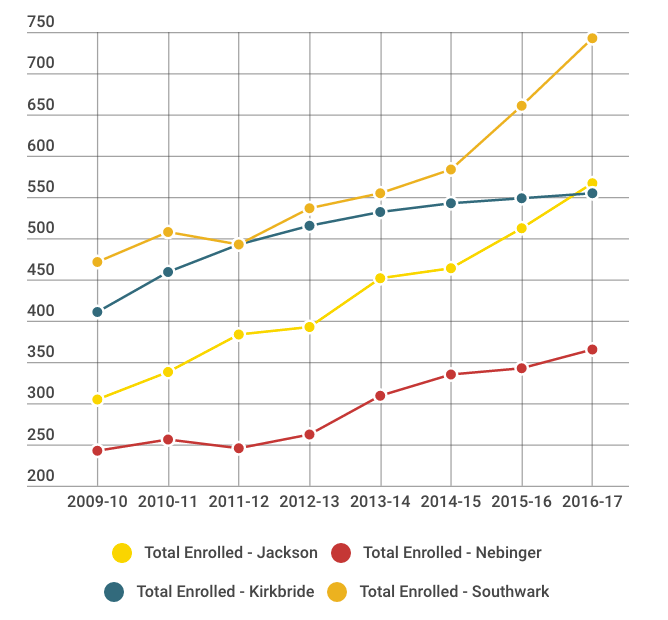

All across South Philadelphia, immigrant families have contributed to an enrollment boom. Since 2009-10, Eliza Kirkbride School near Pennsport has grown 35 percent, George Nebinger School on the border of Queen Village and Bella Vista has grown 50 percent, and Southwark School in East Passyunk Crossing has grown 58 percent. Jackson’s growth has been the most astounding — 86 percent over seven school years. And all this at a time when the school district’s total enrollment has dropped 19 percent.

What’s interesting at Jackson is that, in relative terms, the school has not become more popular among neighborhood residents.

In 2011-12, about 48 percent of children who lived in the Jackson catchment chose to attend the school. The remainder chose to attend a private, charter, or public school in another area. This year, 47 percent of eligible children opted in to Jackson.

So if a greater proportion of neighborhood families aren’t choosing Jackson, then what explains the astounding growth?

For starters, the number of eligible children has grown — from 553 in 2011-12 to 732 this year. Jackson has also become an increasingly popular destination for transfer students.

Through the district’s voluntary transfer students, families can choose any public school that has the space to accommodate them. Since 2011-12, the number of out-of-catchment — or non-neighborhood students — at Jackson has spiked from 117 to 220, a clear sign of the school’s improving reputation.

That figure, however, is about to drop.

Cutting off the transfer student pipeline

Starting next school year, Jackson will no longer be eligible to take voluntary transfer students due to its lack of space. According to the district’s 2013 facilities master plan, Jackson has already surpassed its 517-student capacity. Principal Kaplan expects more than 600 students to walk through the doors next school year.

Cutting off the transfer-student pipeline will likely provide some immediate relief at Jackson, but some parents worry about its long-term implications.

The theory goes like this: As Jackson’s catchment becomes whiter and wealthier, the only way to maintain ethnic and economic diversity will be through transfer students. If the district permanently ends voluntary transfer, Jackson will become an island of relative privilege in an otherwise high-needs school district.

“If people care about diversity they have to make the neighborhood school available to people outside the catchment,” said Wilde, the sociology professor and Jackson parent.

Right now the notion that ending voluntary transfer will change Jackson’s demographics is mostly theoretical. As the chart below shows, the Jackson students who live out of catchment have a similar demographic profile to the Jackson students who live in catchment. In fact, the numbers suggest allowing more transfer students would actually crowd out African-American students and increase the school’s Asian population.

| African American | White | Hispanic | Asian | |

| IN CATCHMENT | 28% | 23% | 32% | 8% |

| OUT OF CATCHMENT | 16% | 23% | 35% | 16% |

There is, however, precedent for the trend that Wilde and other parents predict.

In the mid-2000s, the school district teamed up with Center City businesses to create the Center City Schools Initiative — a branded attempt to promote certain downtown schools and make them appealing to “knowledge workers” who had historically raised their children in the suburbs. The initiative largely achieved its intended purpose, said Maia Cucchiara, a Temple University education professor who penned a book on the project.

As a result of their growing popularity, however, several of the schools at the heart of the initiative curtailed the number of voluntary transfer students. Gradually, many students from the city’s poorer neighborhoods who had used downtown schools as an escape hatch found that path closed to them.

“It became harder for kids outside Center City to have access to those schools because the spots were taken by white, middle-class, upper-middle-class students,” said Cucchiara. “In some ways, the success of the initiative was not necessarily widespread.”

Though the wealthier newcomers often brought much-needed resources to bear, Cucchiara found they tended to prefer fundraising projects that directly benefited their children. The results were schools where lower-income parents could feel less important and less welcome.

“You can end up valuing one kind of parent — the parent with resources — and devaluing another kind of parent — the working class parent,” said Cucchiara.

These facts aren’t lost on many of Jackson’s middle-class parents, and there have been attempts to address the increasingly obvious privilege divide.

Last year, for instance, Friends of Jackson held its second spring fundraiser and used the proceeds to install air conditioning units on the building’s top floor.

The idea grew from an initiative launched by Yuliana and Maria Flores, two Latina mothers from Acapulco who had been agitating about the unbearable conditions for over a year. The building’s top floor is reserved for older students. Because many of Jackson’s middle-class students are relatively young and educated on the school’s lower levels, Friends of Jackson parents were literally unaware the third floor lacked air conditioning until the group of moms brought it to their attention.

The episode speaks to what Cucchiara calls the promise and peril of Philadelphia’s public school boom. Middle-class parents can indeed marshal resources and expertise that benefit lower-income families. And plenty of research suggests that mixed-income schools benefit all involved.

Yet the fact that members of Jackson’s main fundraising arm didn’t realize what the third floor of their school felt like speaks to the quiet divide that can emerge in a transitioning school.

“One solution doesn’t exist…”

There is, as far as the public knows, no grand road map for how to deal with South Philadelphia’s emerging school capacity woes.

“One solution doesn’t exist for all of the schools that are in South Philly,” said Fran Burns, the district’s chief operating officer.

So far solutions have indeed emerged school by school.

At William Meredith School in Queen Village, the district recently implemented a kindergarten lottery — though it promises that all families in the catchment area can return to the school for first grade if they don’t make the initial cut. There’s also talk of merging Meredith with nearby Nebinger School by turning one into a lower school and another into a middle school. District officials say that option is on the table, but hasn’t been decided upon.

At the late March meeting to discuss overcrowding at Jackson held at Hawthorne Recreation Center, Burns ran through the full menu of potential solutions at Jackson.

First, the district will look to maximize all available space in the current school. In the future, it’s possible the district could look to expand the school by leasing space, adding trailers, or tacking on an addition. It’s also possible the district would truncate the number of grades at Jackson or redraw the catchment boundary lines so that less students are eligible to attend the school.

District officials won’t say right now which of these remedies they prefer — only that these are the potential remedies.

Each solution presents its own problems. For Jackson to maximize space it may have to repurpose its library or computer room, two rare amenities that help entice middle-class parents. There’s also the possibility Jackson ditches its Head Start pre-K program, which serves students living at the federal poverty line or below.

Leasing space or adding trailers also seems problematic given Jackson’s relatively tight quarters and its high density neighborhood.

In Northeast Philadelphia, the other part of the city where public school enrollments have sky rocketed, the district has recently completed seven capital projects to help expand capacity. Total price tag? $158.5 million.

One wonders, though, if there is the available space and money to execute a similar plan in South Philadelphia.

Any plan to redraw catchment boundaries or institute a lottery will likely incur blowback from families who have paid a premium to buy homes in the Jackson feeder pattern. Parents also fear that these sorts of solutions will spook future homebuyers and depress development. It’s easy to see why someone considering a $400,000 row home in the Jackson catchment might feel inclined to look elsewhere if there’s no guarantee their child will get into their preferred school.

Still other parents would prefer the district create a new school — perhaps a South Philadelphia middle school — that can alleviate overcrowding pressure and allow schools like Jackson to continue accepting voluntary transfers. That solution, of course, would require a massive capital investment.

Whether Jackson remains the uber-integrated and uber-desirable school it is today will likely depend on which one of these imperfect choices the school district makes.

“We have to decide what we value,” said Dare Henry Moss, a Friends of Jackson member and parent of two children who are about to become school-aged. “These are big, hairy problems.”

If the solutions aren’t clear, at least the stakes are.

The neighborhood around Jackson is a microcosm of a growing Philadelphia. Just as a recent influx of immigrants and white-collar professionals has reversed 50 years of population loss in the city, the renaissance in South Philly’s public schools has helped the district tread water after years of enrollment decline.

In the last three years, the district has held steady at about 134,000 students — a notable achievement considering the freefall that preceded it. Major enrollment growth in Northeast and South Philadelphia is a big part of that story, said district officials.

The result at Jackson is a thriving school with textbook diversity. Now the question is how to keep the momentum.

—

Correction: The new countertop in Jackson’s main office was donated by Ballinger, not Ballard Spahr as originally stated. The article has been updated to reflect this change.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.