In Philly, an academic approach to school repairs

The majority of the Allen M. Stearne School in Frankford, built in 1966, looks every bit it's age.

-

School District of Philadelphia Superintendent Dr. William Hite (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

One of the modernized classrooms at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city, August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

One of the modernized classrooms at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city, August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

One of the modernized classrooms at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city, August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Before-photos are shown at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Superintendent Dr. William Hite, Stearne Principal Mecca Jackson and SPD Education facilities Planner Paula Sahm demonstrate some of the learning materials at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford Section of the city, on August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

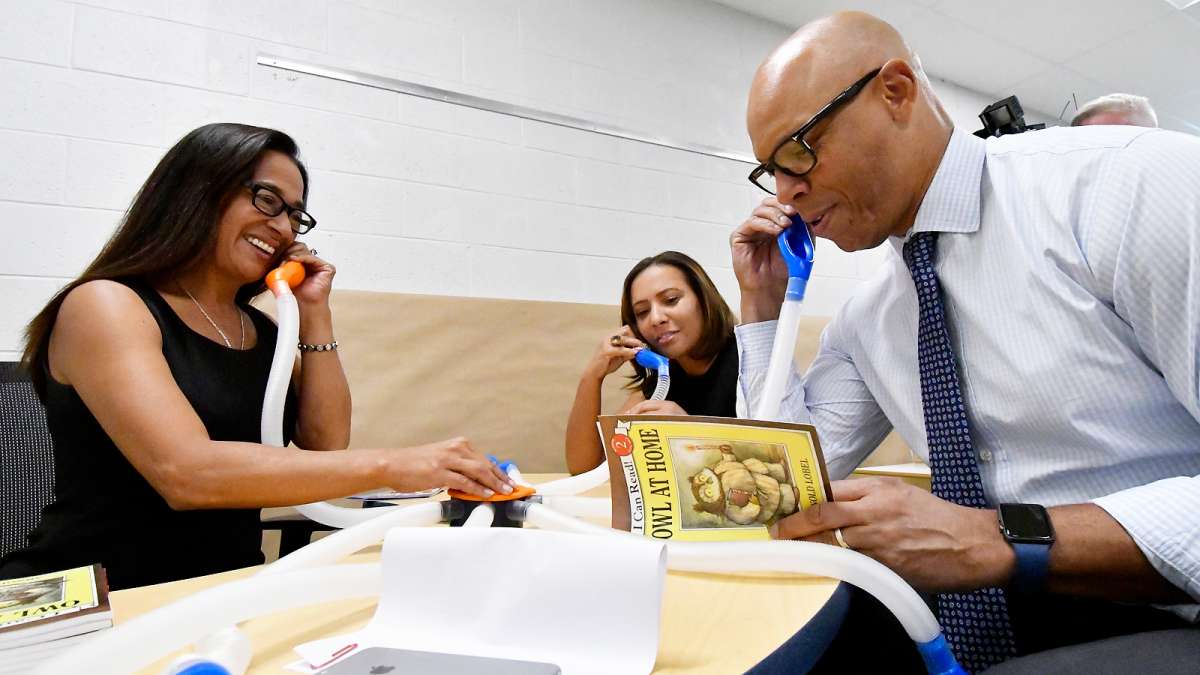

SPD Education facilities Planner Paula Sahm, Stearne Principal Mecca Jackson, and Superintendent Dr. William Hite demonstrate a whisper phone at Allen M. Stearne Elementary (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

SPD Education facilities Planner Paula Sahm, Stearne Principal Mecca Jackson, and Superintendent Dr. William Hite demonstrate a whisper phone at Allen M. Stearne Elementary (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Superintendent Dr. William Hite, Stearne Principal Mecca Jackson, and SPD Education facilities planner Paula Sahm demonstrate some of the learning materials at Allen M. Stearne Elementary (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

SPD Education facilities planner Paula Sahm demonstrates some of the learning materials. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Ahead of the start of the new school year, Superintendent Dr. William Hite tours modernized classrooms at one of eight schools involved in the initiative, Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city, on August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

One of the modernized classrooms at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city, August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

One of the modernized classrooms at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city, August 23, 2017. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Carpet in one of the modernized classrooms at Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

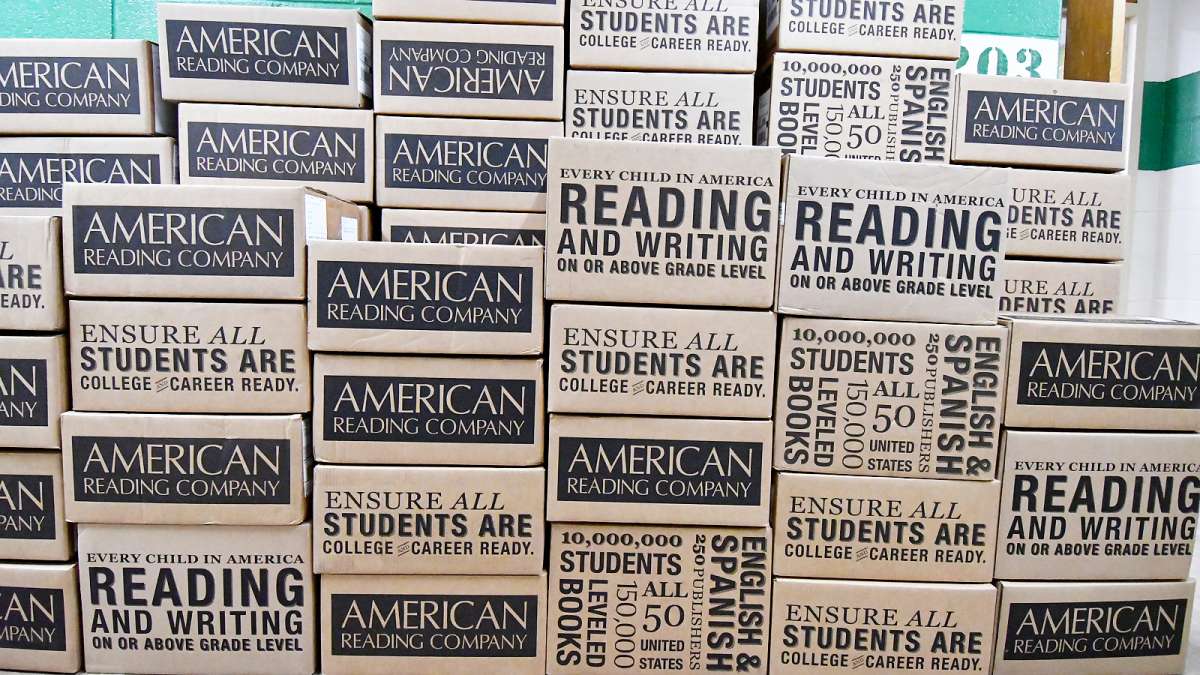

Materials, ready to be used, are piled up in the hallway of Allen M. Stearne Elementary, in the Frankford neighborhood of the city. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

The majority of the Allen M. Stearne School in Frankford, built in 1966, looks every bit it’s age. But step into one of the school’s kindergarten, first, or second-grade classrooms and you’ll feel transported to the 21st century.

There’s new smart panel boards, motion-sensitive lights, tabletops that double as whiteboards, and a gaggle of learning toys too numerous to list here.

“I thought maybe a new bookshelf, new rugs,” said kindergarten teacher Kelly Kaczmarek, recipient of a refurbished room. “But all this? [I had] no idea.”

Stearne was one of eight Philly schools to receive a facelift this summer, but not because they were in dire need of repairs. Or at least not on the surface.

Stearne and the seven other schools all posted low reading scores, and the fixes are designed specifically to address that problem.

Under Superintendent William Hite, the School District of Philadelphia has placed extra emphasis on early literacy. Since teaching literacy in small groups is all the rage, every detail in these new classrooms pushes teachers toward that model. The desks, for instance, contain detachable bins so students can easily move from station to station. Parts of the room are color coded so a teacher could easily instruct students to join the yellow group or the red group.

All this represents a pivot in how the district thinks about capital projects. Instead of solely using money to fix schools in dire need of repair or expansion, officials want at least some of their limited dollars funneled toward projects with an overt academic focus.

Hite said the district didn’t want to only spend on “HVACs and roofs, but also the appearance of classrooms and the learning environments in classrooms.”

The district — due to its size, age, and financial insecurity–has an enormous backlog of building repairs. Earlier this year, the district estimated it would need $4.5 billion just to fix its current batch of deferred maintenance projects. It will rack up another $3.2 billion in maintenance costs over the next decade, according to internal estimates.

By tackling projects based on academic need — rather than functional need–the district is diverting at least some funds away from that massive backlog, albeit a small portion.

Last fiscal year, the district’s capital budget was around $172 million. The district spent $4.4 million on the classroom updates, with the William Penn Foundation kicking in another $700,000.

Hite said it was important for some of the district’s capital budget to go toward projects that make a direct difference to teachers and students.

“It’s really important that our young people, our staff members, and, quite frankly, families, experience something very different than the old, dark buildings that we traditionally have,” said Hite.

“We still have to fix the leaky roofs,” he added. “But part of the investments are also creating excitement around the learning environment.”

Philadelphia has a civic goal of ensuring all students can read on grade level by the time they reach fourth grade, and Hite has made improving early literacy a central focus of his overall strategy. As a result, the remodeled classrooms all serve students in 2nd grade or below.

The remodeled classrooms also received fresh paint, new floors, and a heap of new books.

Kaczmarek, the kindergarten teacher is excited for the new room and all its toys. And she’s especially excited she won’t have to go to Wal-Mart this year to buy more classrooms supplies.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.