In Common: 6 ways Philly can create more equitable, imaginative and inviting public spaces

I was lucky enough to spend 2018 writing the In Common series, exploring the ways civic spaces across Philly are changing, each aiming to build a stronger, more inclusive city

Parkside picnicking during 2018 West Park Arts Fest (Neal Santos for PlanPhilly)

I was lucky enough to spend 2018 writing the In Common series, exploring the ways civic spaces across Philly are changing, each aiming to build a stronger, more inclusive city. We’ll be seeing more of these kinds of projects in more neighborhoods, as Rebuild gathers steam over the next year. Each project is a chance to learn how to do this civic work better. In that spirit, I offer a wishlist for what I’d like to see more of in 2019.

Community Compensation

Walk up to the Discovery Center’s dramatic entrance and you’ll see the names of the project’s major donors written across the new environmental center’s front window. There, alongside names like the William Penn Foundation and Pew Charitable Trusts you see another: Strawberry Mansion CDC & NAC, two of the project’s most dedicated neighborhood partner organizations.

It’s high time the neighbors dedicated to shaping public spaces be reflected as generously as a project’s deep-pocketed donors. But we should be able to do better than making sure community representatives have a meaningful seat at the table or a plaque at the end. Where it makes sense, they ought to be compensated as project consultants. Their citizen expertise, time spent organizing, connecting communities and providing project information to neighbors are resources of real value.

Engagement expertise

Too many city agencies and nonprofit organizations think they can do civic engagement – or that they’ll learn as they go – but it’s more demanding than most realize.

Engagement is not holding a public meeting or providing information about an already-designed project. Effective public engagement requires a focused strategy, clarity about what the public will be able to shape by participating, and approaches that are nimble enough to sustain trusting and responsive relationships with communities. It requires cultural competencies, knowledge of neighborhood networks, language skills, and deliberate design that too many organizations lack or have no ability to pay for through project-based grants. It’s real work that needs to be baked into project budgets.

It’s time we saw more project teams involve community engagement experts early on to help design and implement a tailored engagement plan to drive active and meaningful participation. Project planners should be meeting communities where they are, reaching beyond the usual suspects apt to raise their hands first or speak the loudest.

Engagement is not transactional. It takes time and it should ultimately be about co-creation. So while we’re at it, let’s ditch the language of engagement that “empowers” communities. That just cements old power dynamics in place. I’d love to see more projects where power is shared.

Art practice

Philly’s public space projects increasingly include artists who help create new conversations about change, helping us see familiar places anew. AtHatfield House, a historic building at a gateway to Strawberry Mansion, neighbors have been coming together through artistic experiences and community discussions with an assist from artists-in-residence Amber Art and Design. It is not a product-driven or decorative creative process, but a transformative vehicle for organizing and building power.

Prioritizing creativity helps emphasize the common currency of imagination. That can be instructive for project partners who need to learn the culture of a place early on, while opening up new ways for neighbors to talk about the future. More projects would benefit from social-practice artists who embed in change processes, particularly in the earliest stages.

Civic leverage

When a neighborhood hasn’t seen civic investments in decades, public space projects might not be where residents might want to spend new money first. But these projects can be effective catalysts for communities to address a broader set of issues. But that work can’t be on neighbors alone. Project partners, particularly high-capacity nonprofits or city agencies, should plan and budget for parallel-track work: one to advance the project and another that directly supports neighbors as they organize around near-term needs by helping make new connections to resources and organizations.

In East Parkside, for example, Centennial Commons is phased, which gives time to test collaborative ideas and build community capacity. Project partners and neighborhood organizations are working together to support community-driven programs around public health and urban sustainability, including tree plantings, green neighborhood economy workshops, and the Parkside Fresh Food Fest in summer. It’s a holistic and sustained approach to community development that leverages the public space investment toward multiple, interconnected goals, and is helping build trust.

Design dreams

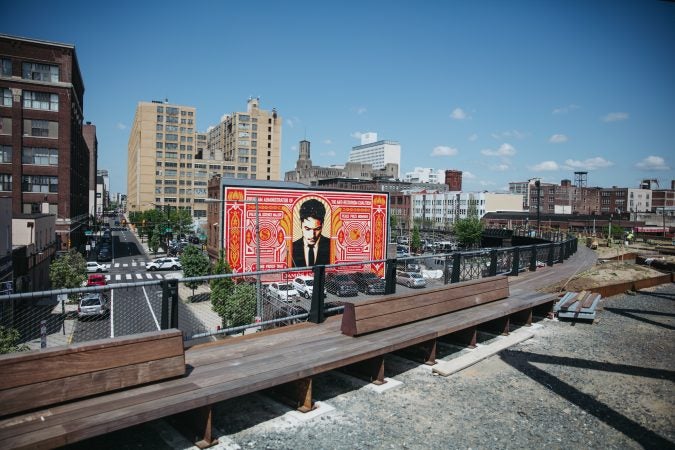

Too many neighborhoods have grown accustomed to living on starvation diets. So when you ask what people want to see in a new or revived public space, their minds often rush to simple solutions like nets for basketball hoops or benches. High design aspirations these are not. But design teams can do more to help Philly’s envision its public space potential. I’d like to see neighborhood design expeditions that spark our public space imaginations. Members of the local Civic Commons network have been able to learn from similar public space work in other cities. More community stakeholders should have opportunities to explore comparable projects.* There is creative work happening in public space worldwide, which designers are constantly learning from. Why not invite communities in on the process? Imagine virtually visiting an revamped public pool in Los Angeles or a colorful plaza in Copenhagen, or maybe taking a bus to see a waterfront park in Newark or library play spaces in North Philly. By finding examples that resonate with communities, new or rehabbed civic space projects might be able to avoid the traps of design-by-committee, giving designers more freedom to boldly adapt our public spaces. All neighborhoods deserve design excellence and room to dream.

Value capture

It’s no surprise that public space investments can boost real estate values, and it is time Philly got serious about putting some of that increased value to work. To park boosters, value-capture strategies could create dedicated funding streams to invest in building or maintaining public spaces. But neighborhood advocates might have a different vision. Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation, for example, has openly wondered about how rising real estate values around the Rail Park, could be leveraged to support affordable housing. Philadelphia isn’t in the business of managing decline anymore, and it is time for the city to seriously consider matching public space investments with tools that encourage equitable growth.

*Disclosure: Civic Commons is locally funded by the John S. and James L. Knight and William Penn foundations. Both foundations provide grant support to WHYY.

The In Common series was made possible through support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.