Imagining a better way to fly

Existing conditions at PHL

Sept. 1

Part 1 of two parts

By Arrus Farmer

For PlanPhilly

On both local and national fronts the ongoing infrastructure discussion has focused on road and bridge maintenance with some talk of local transit and high speed rail. Philadelphia International Airport (PHL), arguably the most important place-based piece of transportation infrastructure in the region, is planning some major changes and would be investing considerable money doing it.

PHL is a gateway to the Delaware Valley for the more than 32 million travelers who pass through it annually. For many of the 4 million international passengers the airport is both their first and last impression of Philadelphia.

But the airport is more than just a point of entry and departure for the region. PHL employs about 32,000 people. With excellent transit connections and thousands of jobs at various skill and education levels it provides opportunity for a broad spectrum of the region’s workers.

According to the PHL website, the airport contributes an estimated $14 billion to the region’s economy annually, making it a vital incubator for economic activity.

The FAA groups PHL with 16 other major airports as a part of the New York – New Jersey – Philadelphia Region, which accounts for roughly 70 percent of U.S. air traffic overall. The Philadelphia Airport is a major hub of this system and is the 10th busiest airport in terms of operations in the country.

Those who have flown from Philadelphia though know how often the PHL experience can be a negative one. Chronic delays and repeated check-ins for international travelers are among the most common complaints. PHL ranks sixth among the slowest airports in the country with an annual average flight delay of over 10 minutes. (The FAA threshold for an acceptable delay is 5 minutes)

These delays can stick in the memory banks of visitors who play such a vital role in the city and regional economy. It doesn’t end there though; delays in Philadelphia cause a ripple effect of missed connections and wasted time throughout the global airspace network. The FAA estimates that air traffic delays in this country cost users, air carriers, and others roughly $46 billion annually in wasted fuel and missed connections. Some $217 million of that cost can be directly attributed to PHL.

Calvin Davenger, Deputy Director of Aviation at PHL’s Planning and Environmental Stewardship Office sources most of this delay to inadequate facilities and flight capacity at PHL.

The current runway configuration is inadequate for the volume of air traffic landing and departing PHL: the two main runways are too close together for simultaneous arrivals, and another can only be used to land and start in one direction, greatly limiting its utility. If the burden on the existing runway infrastructure was not heavy enough, passenger volumes at PHL are expected to double by 2020, making planning and improvement absolutely necessary for both the region and the entire airspace network.

With that need in mind, a 2002 presidential executive order was issued to streamline an environmental impact study to set comprehensive development strategy and detail expansion and construction at PHL through 2025. That process began in 2003 and is still going on today with results and prescriptions expected sometime next year. In the meantime, several projects have begun to improve operations and address delays in the near term at PHL.

In 2007 the Federal Aviation Administration initiated a five-year, four stage airspace redesign of the New York – New Jersey – Philadelphia Region, which will dovetail the facility upgrades on the ground to create a more efficient air travel system for the eastern seaboard.

In June, over $26 million in recovery funds were allotted to a new baggage system, which will make international connecting passenger’s lives easier by automatically checking their baggage through to connecting flights. While this will alleviate some of the pressure on TSA employees and facilities it isn’t the kind of infrastructure improvement that Calvin Davenger is focusing on.

These projects don’t relieve the burden on the existing runway network and therefore don’t have the long-term capacity building that is needed to cut delays. Mr. Davenger stresses the need for “operational relief for the demand projected in 2025: putting the infrastructure in place, the pavement on the ground and making the necessary enhancements to taxiways and terminal complexes for when the projected increase in operations hit.”

In May of this year, a small step was taken in that direction by lengthening commuter runway 17-35 by 1,000 feet. According to a PHL press release from May, the project cost nearly $70 million but is expected to save airlines and passengers $49 million annually and cut more than 11,000 hours of delay from PHL’s operations in 2010. Because of its independent impact and scope, the project to lengthen 17-35 was able to undergo a separate, less arduous Environmental Impact Statement process to receive its approvals and push to speedy completion.

The results of the 17-35 expansion give promise to the eventual effect of the long-term EIS that is underway today. The process of airport planning, however, is long and complex. The current EIS has been conducted to include public hearings, several feasibility studies, and requires permits from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, the federal EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers. Despite several setbacks, Mr. Davenger remains hopeful that the process will yield a blueprint for expansion that will better meet the needs of passengers and the requirements of the Federal Aviation Administration.

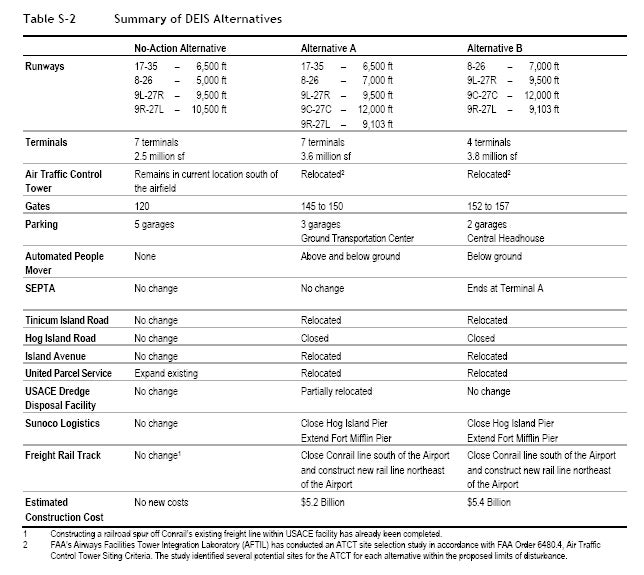

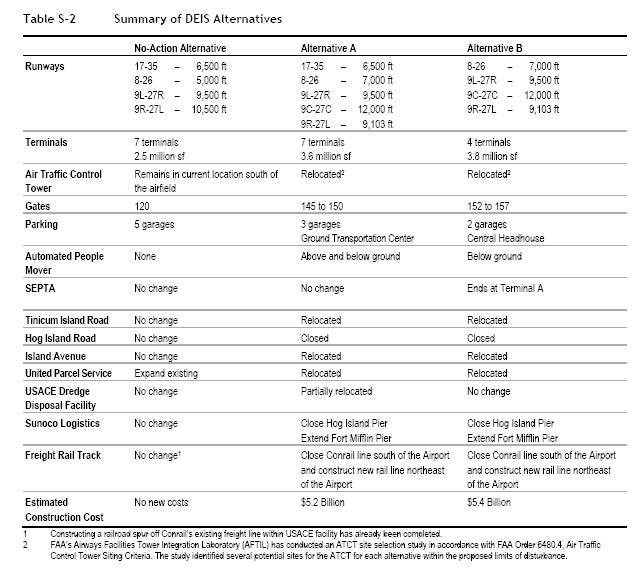

There is some light at the end of the tunnel. Recently, a series of development alternatives were evaluated and three were sent to the FAA for final selection. The table below summarizes a No-Action Alternative as well as options A & B. Both add significant runway space and cut delays in half by 2020.

Source: FAA Draft EIS for Philadelphia International Airport

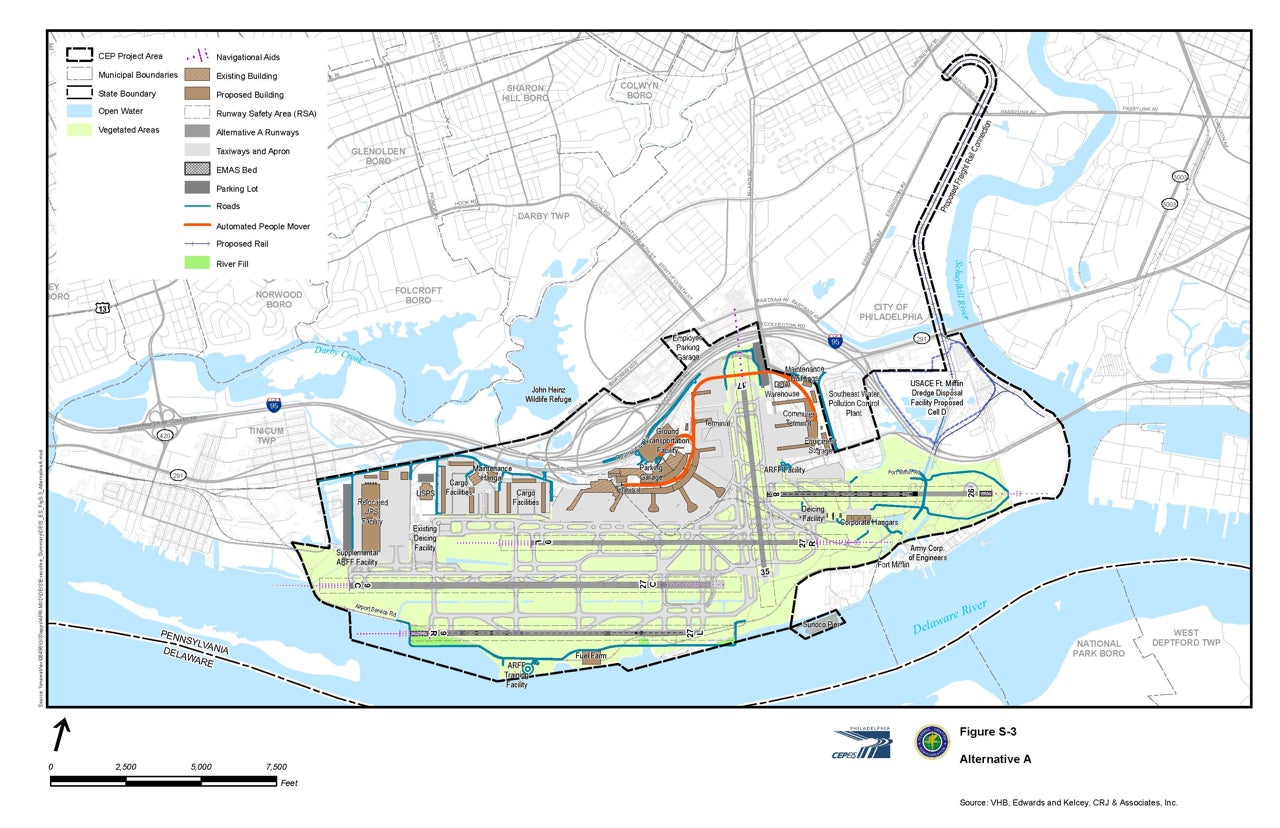

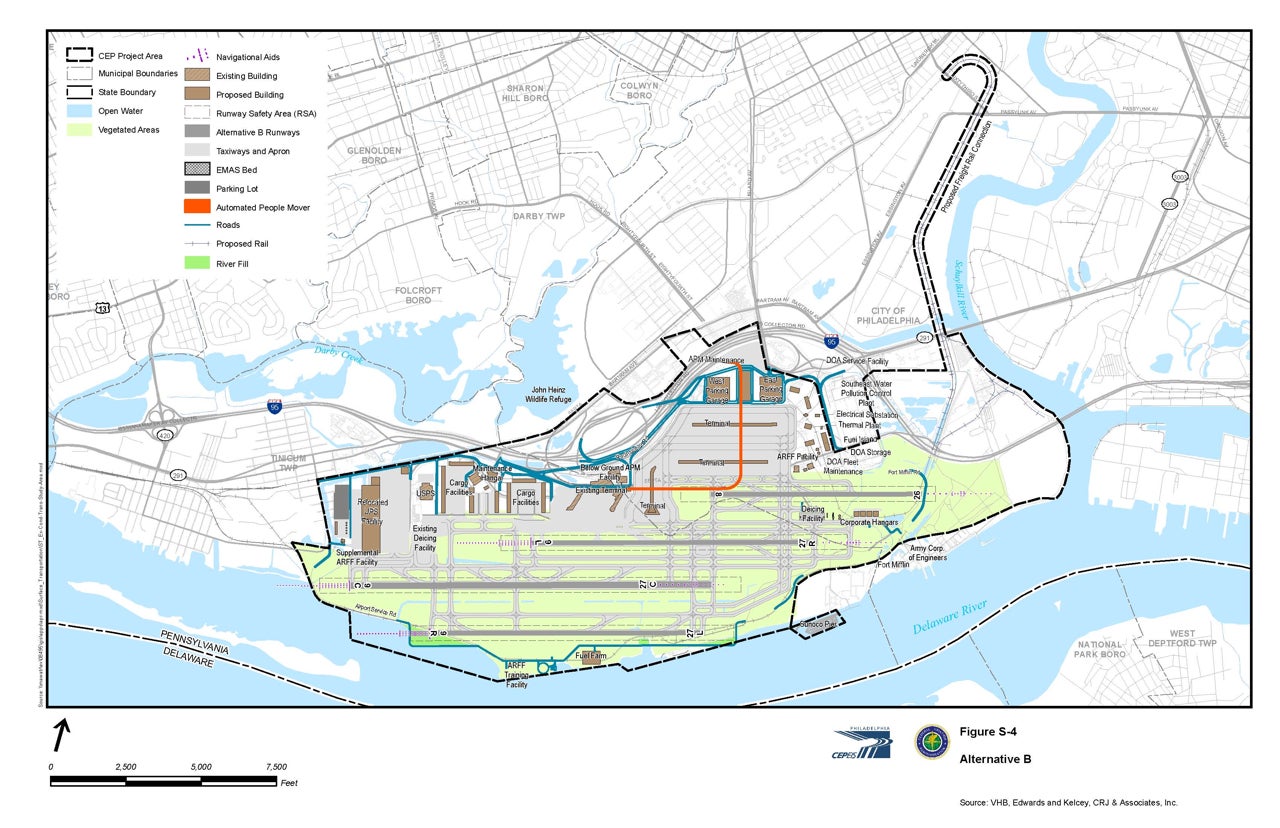

Alternative A comes in at a price of $5.2 billion, recommends the extension of three existing runways and the construction of a fourth. Alternative B, costs $200 million more, adds a fourth runway, strikes one, and extends two, calling for a new configuration of the terminal buildings.

Both A and B show drastic improvement in delay time: projecting a reduction in 2020 annual average delay to 5.3 and 4.7 minutes, respectively. They also call for the construction of a “River Runway” located along the river banks, partially built on reclaimed land to be constructed from the soil dredged from the Delaware. This alignment creates increased distance between the two major runways allowing for simultaneous landings and greatly improving operational capacity.

At this point, however, it is up to the FAA to pick the best alternative for PHL, the city, and the national airspace network. The incredible importance of the airport in the economy and identity of the region means there is a lot at stake for Philadelphia, a lot more than the $5.2 billion being invested there.

Next week, PlanPhilly will take a look at the connections between PHL and the region it serves. We’ll be digging into some international best practices to further explore multimodal connections and see how Philadelphia can better leverage an international travel hub seven miles from its urban core.

Arrus Farmer was most recently a Robert Bosch Fellow based in Berlin, Germany working in the planning and administration of large scale public-private developments. He holds both a Masters of City Planning and a Masters of Government Administration from the University of Pennsylvania which were completed earlier this year. Farmer has worked with Praxis on a number of civic engagement projects including the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware Riverfront.

Contact the reporter at arrus.farmer@alumni.upenn.edu

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.