Illustrious life of Penn Museum artist no open-and-shut case

The University of Pennsylvania Museum received a mysterious package last week — a small suitcase that once belonged to an artist who traveled the world documenting archaeological artifacts with her watercolor illustrations.

An antiques dealer bought the suitcase at auction, then reached out to the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology to see if there was interest in paying a few hundred dollars for it.

The museum’s head archivist, Alex Pezzati, jumped at it.

Pezzati held off opening it until Friday afternoon, when he normally does a weekly show-and-tell of selected treasures from the stacks.

About 40 people gathered in the archive room, formerly a grand library reading room, to witness the reveal. A live Facebook stream was there to capture it. There were lots of jokes about Geraldo Rivera’s anticlimactic opening of Al Capone’s vault on live television in 1986.

“We kind of know there’s something in here, unlike the Al Capone safe, which proved to have nothing in it,” said Pezzati, razoring open the packaging tape. “Drum roll, please.”

Inside the package was a locked suitcase belonging to Mary Louise Baker.

First, a little about Mary Louise Baker

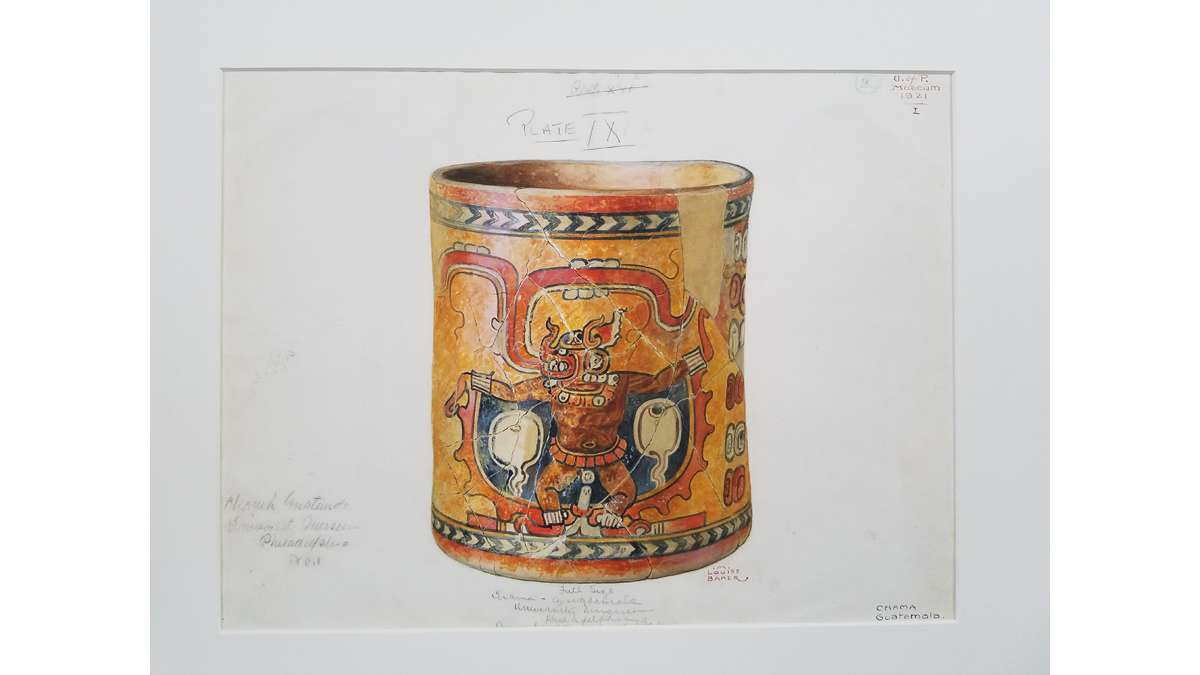

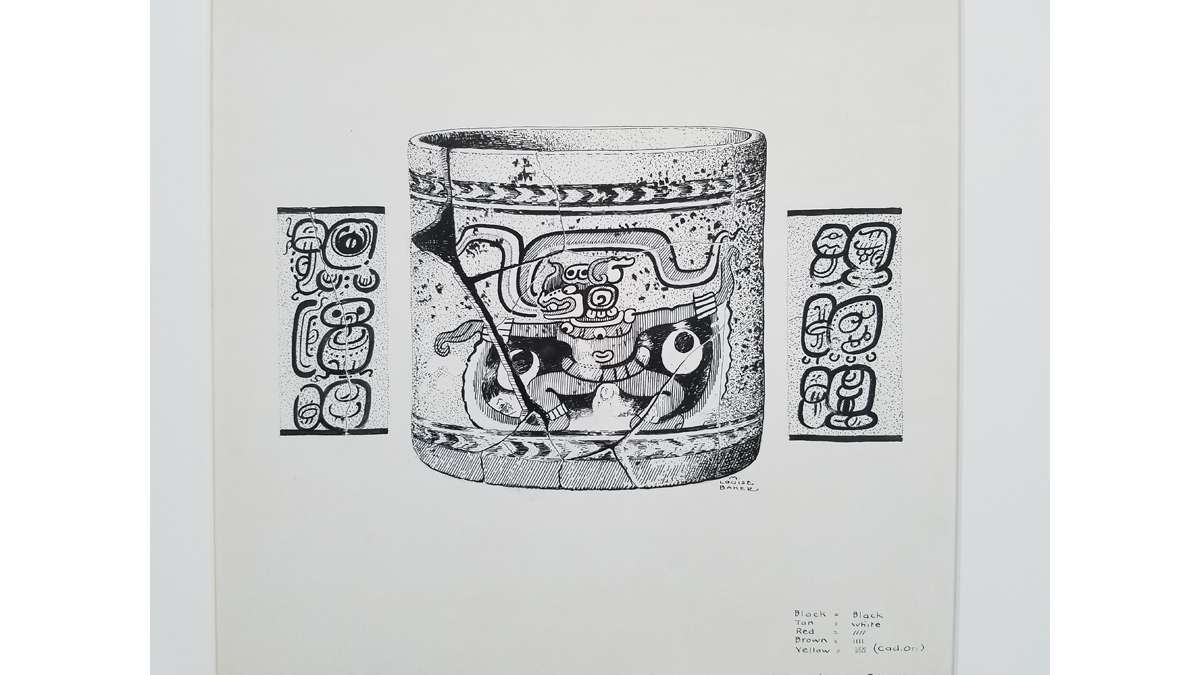

Born in Ohio in 1872, she moved to Philadelphia at 19 to study art at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts). She was hired in 1908 by the Penn Museum as a part-time illustrator. She worked for the museum for almost 30 years, rendering in exquisite watercolor the artifacts from the ancient Mayans, Mesopotamians, and Islamic civilizations.

She was very good at it. She often used an exacting technique called trompe l’oeil (“fool the eye”) to make objects appear to exist in real space, not just on paper. Through illustration, she could assemble fragmented pottery in ways not possible in real life. She could flatten a rounded vase in order to show the whole design in one plane.

The famed archaeologist Charles Leonard Woolley insisted Baker was the only person allowed to illustrate his Ur artifacts.

Baker was also a Quaker. While working in Germany in 1932, just before Hitler rose to power, she wrote of her disgust at the way the Jews were treated. “I don’t like being with people who enjoy hurting others,” she wrote. “No good can come of it, but worlds of trouble.”

She spent much of her time globetrotting from museums to dig sites. When she was home, she lived with her lifelong partner, a woman who was principal of the George School, a Quaker boarding school in Bucks County.

All her life, Baker suffered medical problems, including cataracts, glaucoma and spinal meningitis. At one point, doctors in Wilmington attempted to alleviate the pain of her eyes by applying leeches to her temples.

“The huge leeches were ravenous when released from the box, and quickly fastened themselves to my temples by triangular incisions,” she wrote. “In my most successful nightmares, I recall these leeches.”

Baker believed her life was extraordinary; she wrote a 10-chapter autobiography, which was never published.

Complete blindness in 1949 ended her art career, and she died in 1962 at age 90.

“She was upright and really smart and, um … what’s the word … with it,” said Pezzati. “She was cool. A really cool lady. She was fearless — she didn’t mind going into the jungles of Guatemala. She wasn’t your typical woman or artist.”

And the revealPezzati suspected there would not be much inside the suitcase, and he was right. After struggling with the suitcase locks, he popped them crudely with a screwdriver. Inside were few photographs, a small, empty notebook, and a 1932 letter written en route to Baghdad.

Nevertheless, he was excited by the find. The museum is already the repository of Baker’s papers, including hundreds of drawings and her diaries donated a few years ago by her family.

Coupled with the few material objects like this travel bag and artist tools, Pezzati can create an exhibition about the extraordinary life of this mostly forgotten artist.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.