Drawings help reveal the creative process at Princeton University Art Museum

Studying Italian master drawings is the cornerstone of an art history education, and Princeton University has one of the most extensive collections of Italian master drawings, with more than 1,000 drawings showing styles and techniques by artists from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

A new exhibition, 500 Years of Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum, showcases more than 100 of these treasures from the 15th through the early 20th centuries, and includes rarely seen works by Bernini, Michelangelo, Modigliani, Parmigianino, Giambattista and Tintoretto, among others. It’s on view through May 11.

The exhibition is organized by theme to demonstrate the role of disegno, or drawing, in the Italian design process. In “Technique,” examples of wet techniques, such as pen-and-ink, are shown, including one on parchment. PUAM Curator of Prints and Drawings Laura Giles says most of the drawings are on paper. “Paper was invented in China and available in Europe by the 14th century. Paper mills started to form by rivers. Paper makers would create a watermark to identify their product, and this can help to date a drawing.”

“Drawing as Discipline” explores the important role of copying in artistic education. “Embedded in the training of Italian artists by the middle of the 15th century…, disegno provided an enduring impetus for future generations to conceptualize a design and then realize that mental image on paper – the first mark-making step toward the project’s final realization on canvas or in stone,” says Giles. “Disegno played a significant role, beginning in late 14th century Florence, in elevating the status of painting, sculpture and architecture from manual craft to liberal art.” Florentine painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote that disegno was the father of all the arts.

The section “Stage of Design” takes the viewer from first thoughts to the final painting. We learn that this process began, in the early 16-century, with rapid brainstorming sketches, called schizzi and primi pensieri, or first thoughts, followed by studies of individual figures, or studi, and culminating with modelli – finished drawings. There are examples contrasting Venetian colorito – broken contours and smudged shadow drawing – and the Florentine disegno, expressed in long continuous contours and precise modeling.

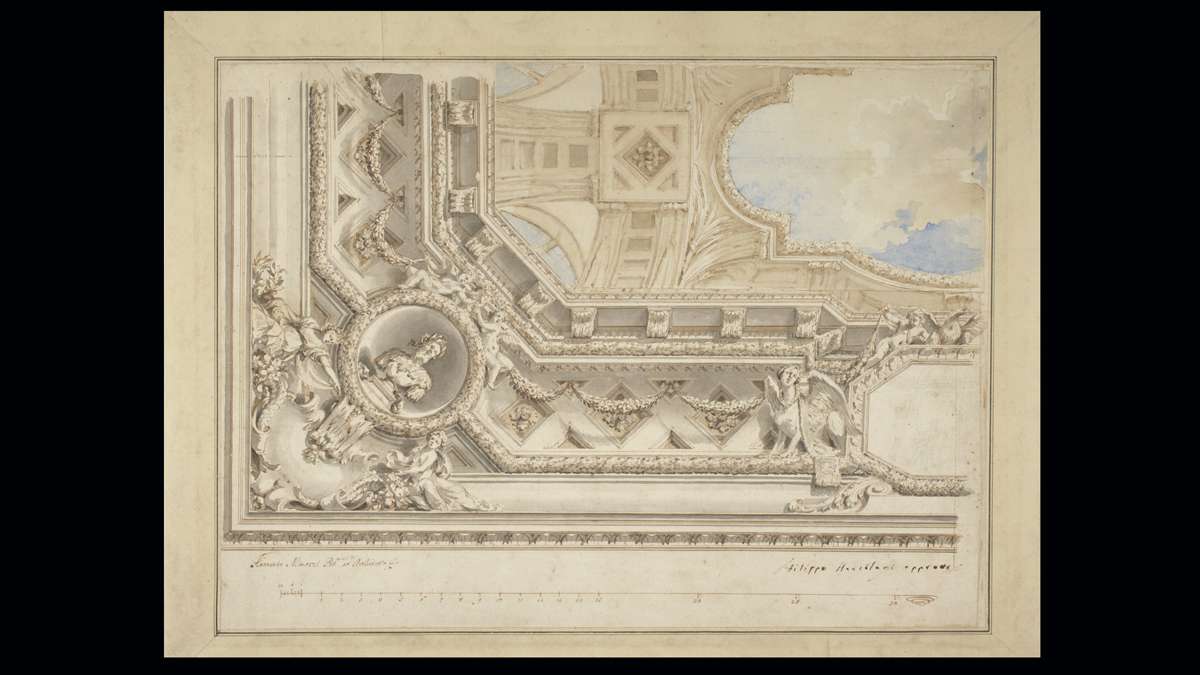

“Autonomy of Expression” shows the growing importance of drawing as an autonomous and collectible work and presents the design for a late 18th-century Bologna ceiling by Flamino Innocenzo Minozzi.

PUAM acquired these rich holdings thanks largely to two men: Frank Jewett Mather Jr., the second director of the museum (he served in the 1920s to the 1940s), and Dan Fellows Platt, Class of 1895.

Mather – with a PhD in English philology and literature at Johns Hopkins University — traveled to Berlin to study Italian art and then studied at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes in Paris. He moved to Paris in 1901 to accept a job as an assistant editor of The Nation and then as editorial writer for the New York Evening Post. In 1904 he began writing art criticism for the Post.

Mather contracted typhoid fever and moved to Italy to recuperate, working as a freelance journalist. In getting acquainted with the expat community, he met Allan Marquand, founder and major benefactor to Princeton’s department of art and archaeology. Mather began collecting Italian art while there, especially the drawings which were affordable. “He first began acquiring as a student – carpets and Japanese art,” says Giles. “His interests were broad. Most of what Mather acquired was American – he collected Arthur Dove watercolors.”

His collection including more than 350 Italian drawings, largely 16th to 17th century. After returning to the U.S., Marquand hired Mather to teach Italian art history, and by 1922 Mather was chosen to direct the museum. During his years as director he acquired his own personal collection, some of which was Italian art. He used the university’s endowments and his own funds to build the core of the European and American painting collection. In 1946 he retired from the museum, donating his collection of prints and drawings to the museum.

Platt — archaeologist, author, lawyer, art collector and the Mayor of Englewood, New Jersey from 1904 to 1905 – was inspired by Marquand and collected Italian Renaissance paintings from Umbria and Siena, as well as drawings. He went to Italy every summer and collected, leaving it all to the art museum after his wife’s death.

Both Mather and Platt sought drawings that could provide teachable moments and transformative experiences, but after Mather died in 1953 the collection wasn’t used much again until the late 1960s, when it became part of a traveling exhibition, the Italian Princeton Collection, through the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The art museum had undergone reconstruction in the 1960s and the Met saw it as an opportunity, according to Giles. Since then, individual works have been shown and have been on loan. The collection is well known among scholars internationally.

Platt (1873–1937) also collected contemporary art of his day, including Modigliani – this was considered “adventurous” at the time, says Giles. “Modigliani was considered avant-garde.”

But Modigliani was largely interested in the figure, and so Platt collected his drawings.

Giles points out that the word drawing goes back to the Anglo Saxon word for making a furrow in the land. Drawings selected for the show are “master drawings,” but not necessary done by the masters, Giles says. “Many of the masters passed along their studies for students to copy, and these were collected by their students.”

So, for example, a work attributed to Tintoretto might be a copy by one of his students.

In organizing this exhibition and its accompanying scholarly catalog, Giles wanted to show continuity through the history of Italian drawing. “People will become aware of so many more artists,” she says. “Drawings are revelatory of the creative process, you can get close to an artist bringing ideas to life in a drawing that you don’t see in painting. People who like Italian art but are not familiar with the drawings will be transformed by this peeling away of the layers of the creative process. In some cases, a drawing records something lost or unexecuted, and serves as documentation. Works on paper may not be big, there are no jewels, there’s no bling, but it’s very intimate.”

500 Years of Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum is on view at the Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton University campus, through May 11. An Italian-themed concert by the Princeton Singers will be followed by a reception in the museum Feb. 15. Curator Laura Giles will discuss “Lasting Legacies, Changing Attributions,” and the collecting and connoisseurship of Italian drawings at Princeton Feb. 20, 5:30 p.m., 101 McCormick Hall.

___________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.