How to do dynamic parking pricing on the cheap – if the Parking Authority wants it

Last week Emily Guendelsberger at City Paper spoke with Donald Shoup, UCLA professor and author of the parking economics bible The High Cost of Free Parking, about Councilman Bill Greenlee’s push to ban apps like Haystack and MonkeyParking.

For a quick refresher, these apps allow people searching for a curb parking space to pay someone else to vacate one a bit sooner. Greenlee and likeminded Councilmembers feel that this undermines their edict that these curb spaces should be unpriced, but as Shoup explains, Council’s determination to underprice curb parking is the entire reason that an arbitrage market exists for these apps to tap into in the first place.

If Council was setting the right price for curb parking, Shoup says, there would always be some open spaces available, and thus no way for app users to make money from publicly-owned curb parking spaces. If every space on a block is taken, then by definition Council is under-charging.

So what is actually the right price for parking? It all depends on the location and the time of day.

Shoup recommends targeting the price so as to achieve an 80% occupancy rate – one or two open spaces on each block – at all times. But since the demand for parking is different throughout the day, he also recommends setting different prices based on time of day, and also location. There’s more demand to park in Center City than in the neighborhoods, for instance. And there’s also more demand to park on neighborhood commercial corridors than residential streets. So he argues that the price for curb parking should vary accordingly.

This practice goes by several different names – “variable rate parking,” “dynamic parking” or “performance parking” – but the idea is the same: parking prices should fluctuate based on demand, rather than remaining static, with the goal of better sorting drivers by their willingness to pay and willingness to walk, and getting them into parking spaces more quickly.

Why does this matter? Shoup has found in various studies that as much as 30% of the traffic congestion on urban streets is attributable to people cruising for parking. Not only is that annoying for drivers (those trying to park, and those driving behind them), it also causes unnecessary air pollution from idling cars. And it also makes things worse for non-drivers too, by making it harder to keep the buses running on schedule – one of the big challenges for growing transit ridership.

The most ambitious effort at variable-rate parking that any US city has tried thus far is SF Park in San Francisco, which Emily describes in her piece:

In 2011, San Francisco used a $20 million federal grant to roll out SFpark, a smart-parking system based on some of the ideas Shoup champions. SFpark uses sensors to track whether parking spots in eight congested areas are occupied or empty throughout the day, analyzes the data, then adjusts prices monthly to nudge occupancy closer to “one or two empty spaces per block at all times.” Drivers can also check an app to see which blocks have more or less parking available, and pay by cell phone.

A study earlier this year found that cruising for parking was down 50 percent in San Francisco since 2011.

This idea has some purchase within the Nutter administration. It made it into the Greenworks plan, with the rationale that it would reduce cruising and cut down on air pollution from tailpipe emissions. They set a goal to implement a similar dynamic pricing model here.

Consider Demand Pricing Schemes for Parking: The Philadelphia Parking Authority set different prices for parking on major commercial corridors depending on the day of the week and time of day. The selected prices and time limits aim to maintain approximately 80 percent parking occupancy, which reduces circling by vehicles searching for parking, and in turn reduces congestion and emissions from automobiles.

The Greenworks 2014 progress report lists this goal as “in progress”, but there’s little evidence the Parking Authority has made much of an effort to implement it.

The recent history of this issue is that City Council, at the urging of MOTU head Rina Cutler, raised parking meter rates from $1 an hour to $2 an hour in 2009, and then authorized PPA to raise rates from $2 to $3 in 2011, only for a small section of Center City and University City.

In the rest of the city, rates are still a flat 50 cents, even on busy commercial corridors. A bill passed out of committee in April authorizing the PPA to raise rates an additional 50 cents to $2.50 in the growing areas outside Center City and University City, and to $1.00 on the neighborhood commercial corridors. That has yet to receive a vote from the full Council.

Cutler had wanted PPA to set curb parking rates to nudge people into a garage after an hour or two:

“If you’re going to be in the city all day, it’s a better deal to be on public transit, or, if you do need a car and you’re going to park longer than an hour or two, you need to go into a garage,” she said.

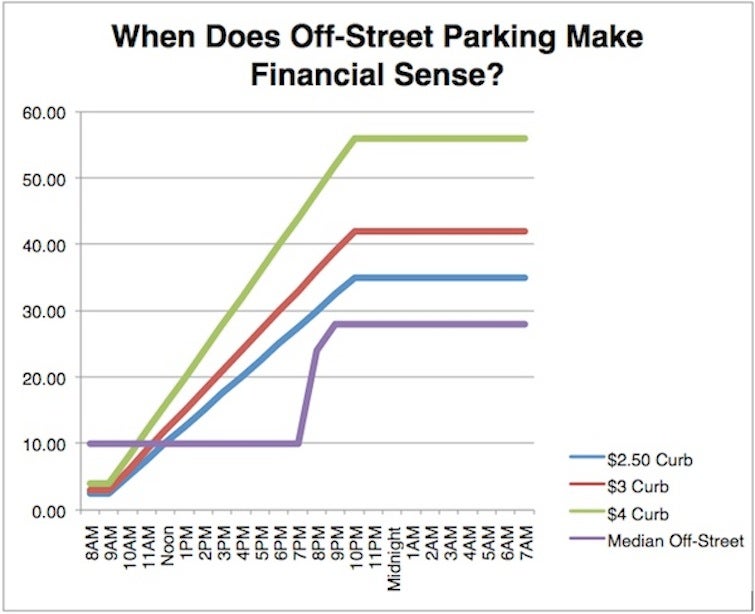

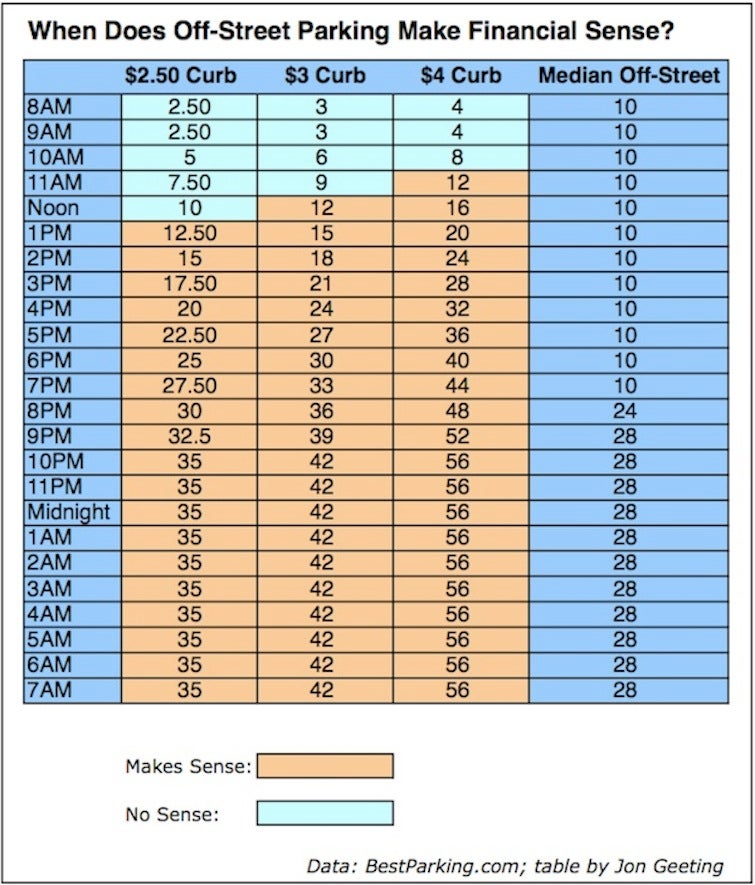

As I showed earlier this year at This Old City, the current prices are too low to achieve MOTU’s stated goal of nudging people into a garage after one or two hours. Using data from comparison shopping site BestParking.com I found that the median off-street parking facility in greater Center City (the Parkway surface lot at 1127 Race St) charges a flat $10 fee to park for under half a day, $24 for exactly half a day, and $28 for a full 24 hours.

And what I discovered was that the garage only becomes price competitive after 2 hours if the curb meter rates are $4 an hour.

Granted, the need to move the car after 2 hours may make off-street parking more appealing thereafter for some, but the prices at least are not currently set at the level needed to achieve MOTU’s goal of nudging drivers off-street after one or two hours.

PPA Deputy Executive Director Richard Dickson told Emily that the PPA is trying to strike a balance between pricing that encourages turnover such as MOTU wants, and pricing that doesn’t offend people’s sense of political fairness.

“We try to find a balance between a fee that encourages turnover and a fee that excludes people because it’s exorbitant,” he told City Paper.

At the PPA’s Q&A with bloggers I asked Corinne O’Connor, director of on-street parking, about PPA’s interest in piloting the variable pricing idea in the Greenworks plan, and she said she was worried that it might dissuade people from driving into the city.

“I don’t know if I particularly like that. I just feel like, as the public if you’re going down, you don’t know what — what I learned talking to people from California is that once that block is filled to 85% capacity, that’s when it will go up. And it can change hour by hour. And as a consumer I don’t know if I would want to come down and like, I want to go to 4th and South and it’s 8pm at night – it could be like $5 for an hour, and in the morning it’s only $2. I don’t know if that’s fair to a person who’s looking to park. I think I’d rather know what I’m going to pay before I come in and be able to make a decision if I want to park in a parking garage or if I want to park on the street. I don’t know if that would have too many people upset.

As it happens, the city of Pittsburgh has been experimenting with a version of variable rate parking that doesn’t require expensive sensors. Instead it uses parking kiosks similar to Philadelphia’s, and some signs labeling areas as either Premium or Economy parking zones.

Since 2013, professors at Carnegie Mellon University have been running a pilot with permission from the city, managing about 400 parking spaces. The pilot was approved in reaction to a policy failure.

“In January 2012, the city raised the rates to $2 an hour,” Professor Mark Fichman told me, “and before then, around the University, they had been a dollar or 50 cents – much lower. The meters were coin-fed, so quarters, and suddenly to park for an hour you needed eight quarters. Parking declined precipitously. There was about 35% occupancy.”

So Professor Fichman and his colleague Steven Spear asked City Councilman (and now Mayor) Bill Peduto to give them the right to jointly set prices with the Parking Authority around an area of CMU’s campus starting in January 2013, when parking kiosks that accepted credit cards would be installed in the area.

They put up signs denoting areas as either Premium parking or Economy parking. Then, at first, they priced the parking near the University at a flat $2, and priced parking further away at less than $2. Unlike SF Park, the prices are changed on a monthly – not daily or hourly – basis.

“If we take $2 as the baseline, approximately 220 of the parking spaces are Premium, and approximately 180 are Economy,” Fichman told me, “The premium pricing fluctuates between $2.25, and $1.50 in the summer, when it slows down and the students are away. Economy pricing, which was $2 before January 2013 has fluctuated between 50 cents an hour, and $1.25 an hour.”

Fichman said the parking occupancy picked up appreciably when the new kiosks were installed. And interestingly, while the Professors have lowered parking prices on average, they’re actually producing more revenue in total. Donald Shoup confirmed the same result with SF Park. When the prices are flat all year long, that means the prices are actually too high most of the time.

In September 2012, when the old rates were still in effect in the pilot area near CMU, the 400 meters produced $55,356 in revenue. In September 2013, with the average price lowered, they produced $79, 659. And in September 2014, it was $90,090.

The professors are also targeting roughly 80-85% occupancy, and their rule of thumb is that if occupancy goes about 85%, then they increase the rate the next month. If it goes below 60% they lower the rate.

How do they know what the occupancy is like without sensors in the curb?

“We get a report from the Pittsburgh Parking Authority every week. When people pay, it’s recorded where they were and what they paid for, so like “on Monday at 8:01 am some guy put money in this meter for 2 hours’ – there are about 4-5000 of these events. And we just wrote the programs to calculate from that the occupancy and the capacity. Then we use that data to make our pricing decisions.”

Fichman says the occupancy numbers are better than they were before, but they’re achieving these results on a much cheaper basis than SF Park. The management cost is lower, and the technology requirements are lower, Fichman says.

Based on the success of the pilot, the Peduto administration and their allies on City Council are now pushing to pilot variable-rate parking citywide. That’s going to be politically trickier, since not every Councilmember is as gung-ho about dynamic pricing as Peduto was. Fichman has encouraged the administration to focus first on reducing the prices on corridors that are priced too high, in hopes of persuading a skeptical public that “dynamic pricing” isn’t political speak for across-the-board rate hikes – it means prices go down sometimes too, and more often than not.

Still, coaxing the rate-setting authority from City Council will be a challenge there, just as it will with Philadelphia City Council.

“The Parking Authority I think likes us, because we’re essentially arguing that they should set the parking rates, not the Council,” Fichman says, “I think the Council is worried about losing control of the rates, which we’ve proposed they no longer exclusively control, but they like more revenue and so on balance they like us. And I think we have to be able to make the case to persuade business people and various groups around the city that rely on parking to support us.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.