Why Americans are obsessed with the number ‘10,000’

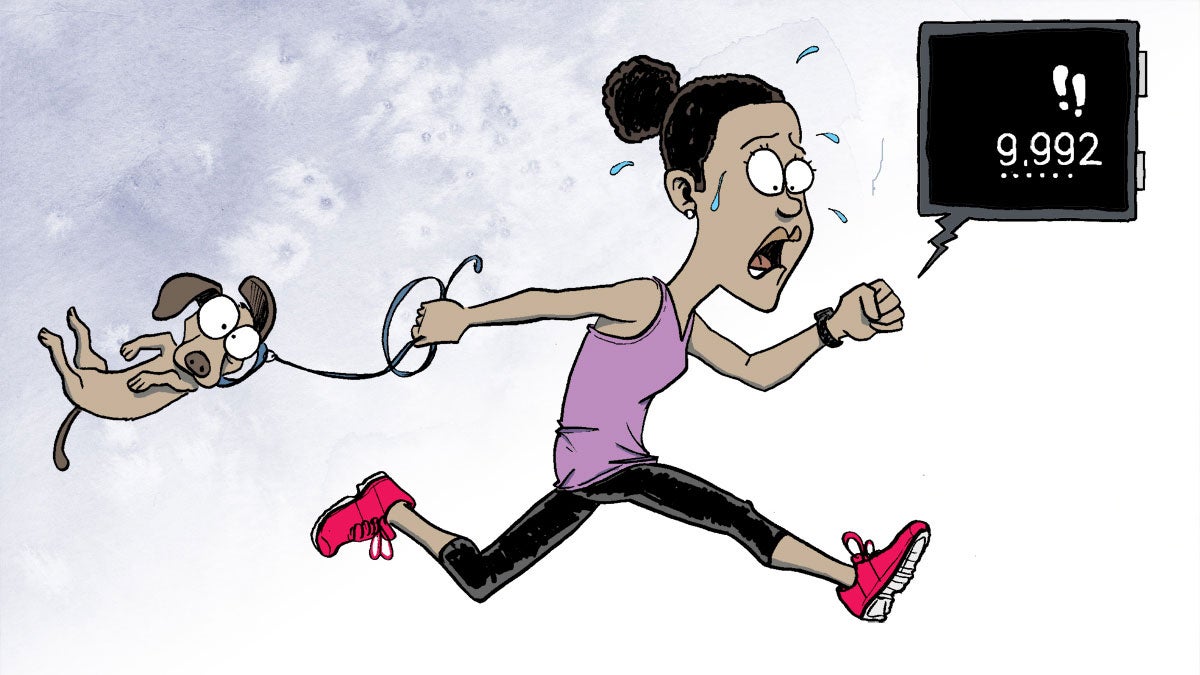

(Illustration by Rob Tornoe)

When Cally Crawford’s Fitbit vibrates on her wrist, alerting her that she’s reached her step goal for the day, it doesn’t typically happen to a soundtrack of Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger,” but this doesn’t matter.

“I feel like I’m Rocky and I’ve just climbed the art museum steps,” said Crawford, 30, who works as a procurement manager for Cape Resorts Group, a collection of luxury hotels and inns in Cape May, N.J. “For a while, I couldn’t go to bed without meeting my step goal. It was a real problem!”

She’s not alone. The global market for step-counting devices — most of which push users to strive for 10,000 steps a day — is on the rise. Just over 60 million wearable activity trackers were purchased in 2016. By 2020, that number will be closer to 440 million. Part of this is down to engineering advancements that allow for a more accurate reading, like the incorporation of triaxial accelerometer technology, which gauges movement from multiple axises (rather than, say, just at the hips, which was the case for early pedometers). In other words, you can expect to see more of your friends power-walking through lunch breaks in the near future.

So, what’s driving this trend and — in some cases — this obsession? Turns out, it’s more than just a collective desire to keep active and stay fit. Newsworks investigated.

Why 10,000?

It’s a nice, round number, and one we’ve increasingly associated with success ever since pop psych writer Malcolm Gladwell purported the controversial idea that 10,000 hours of deliberate practice is all it takes to achieve world-class status in any field, from composing music to playing basketball. But when applied to walking, is 10,000 steps really the key to better health? That may depend on who you are.

It’s a nice, round number, and one we’ve increasingly associated with success ever since pop psych writer Malcolm Gladwell purported the controversial idea that 10,000 hours of deliberate practice is all it takes to achieve world-class status in any field, from composing music to playing basketball. But when applied to walking, is 10,000 steps really the key to better health? That may depend on who you are.

Though Thomas Jefferson introduced the American people to the pedometer during his tenure as third president of the United States, the device didn’t grow in popularity here until the 1930s. And the notion of 10,000 daily steps as aspirational goal didn’t come about until 1964., as Olympic fever swept the globe. At this time, a Japanese man called Y Hatano presented research suggesting this was the ideal way to maintain a healthy weight. He then used this research to promote his manpo-kei (or 10,000 step meter) pedometer.

Despite the fact Hatano’s work was based on the average Japanese man (with a diet and exercise regime very different from that of, say, the average American man or woman), and despite the fact that 10,000-steps-as-health-panacea is not a notion that’s been validated clinically, companies around the world took this number and ran — or, rather, walked — with it.

In other words, your fallback fitness plan is a marketing gimmick. As with diamonds being a girl’s best friend or milk doing a body good, there’s room for debate.

“Different fitness trackers and apps incorporated the 10,000-step idea as gospel, because it is a simple way to sell products, since this is an easy goal for the public to understand,” said Kelly Dougherty, MS, PhD, MTR, Assistant Professor of Exercise Science at Stockton University in Galloway, N.J. “We live in a physical inactivity culture — so, from my perspective, anything that gets people moving is good — but this shouldn’t be a blanket prescription for everyone.”

The problem, Dougherty says, is that the 10,000-step rule doesn’t take into account baseline fitness. Some people — those who aren’t big into walking but spend their free time swimming laps, for instance — may not see improved fitness by hitting the 10,000-step mark every day. For others, like those who’ve been sedentary, 5,000 steps with a plan to make incremental increases may be the healthier, more appropriate, goal. Factor in the margin of error these devices carry (speaking with one’s hands can add phony “steps”), as well as differences in gait (not all walking is created equal), and the 10,000-step rule feels even more arbitrary.

Still, the recommendation is not without some merit. For healthy individuals, The American College of Sports Medicine advocates for 150 minutes of aerobic activity — like walking — per week, in order to develop and maintain physical fitness. And, if one were to complete 10,000 steps per day, he or she would meet this target.

“Ten thousand steps per day is a very nice, very general goal,” said John Smith, PhD, an associate professor in the College of Education and Kinesiology who studies pedometer use at Texas A&M University. “But we have to be careful when we’re prescribing it across the board. It would be wonderful if, on a manufacturer’s website or on their device’s pamphlet, they would include a disclaimer: this may not apply to everyone.”

But whether 10.000 steps is a decent exercise goal for an individual or not, the science is clear on one thing: the simple act of purchasing a step-tracking device serves as a motivational tool, helping to jumpstart a wellness plan and, potentially, change a person’s life for the better.

The Benefits

One of the people for whom tracking steps has improved quality of life is Tim Smith*, a 44-year-old engineer/project manager based in northwest Chicago who leads a team that builds distribution centers. Along with improving his diet, Smith started walking 10,000 steps per day with a Fitbit in August of 2015, and he hasn’t looked back since. This habit kickstarted a fitness journey that led Smith to begin training for an Olympic triathlon this summer.

“Counting steps helped me build momentum,” said Smith, who is down 55 pounds since his peak weight of 275. “I will likely come in last place in the tri — literally — and I don’t care. I just like the idea I couldn’t do this two years ago, and now I can.”

Smith catalogues his journey on his website, steppersstory.com. He also tweets his progress to more than 2,600 followers from the handle @10000_steps_day, a platform that helps connect him to other step trackers while keeping him accountable.

“This creates social pressure, which I find useful,” he said. “I know if the whole thing disappeared tomorrow no one’s day would be ruined, but in my head, it matters.”

The social aspect of step counting is a topic that comes up frequently. While reporting this story, I heard several times that good-natured competition with friends and family to see who can log the highest number is part of the fun, because it provides a healthy way to engage sans a Facebook or Instagram feed. One example is Lori Kraine, a 59-year-old homemaker who lives in Center City, Philadelphia.

“I have participated in Fitbit competitions with friends who challenged me,” said Kraine, who sports a Fitibt tan-line and a personal record of about 24,000 steps in one day. “One was a former neighbor, the other was a woman I hadn’t seen in two years. It was a nice way to reconnect.”

One of the places this happens frequently is the office, where step-counting competitions help break the monotony of a workday. Twenty-seven-year-old Kevin Daniel Baum recently moved from Somerset, New Jersey to Colorado for a different position with the same IT company. In his former office, step challenges among colleagues were de rigueur, and Baum still participates, even though he’s no longer on site.

“I would say it improved office culture,” he said. “It gave us something to talk about at the water cooler, and it got us taking walk breaks. There was a lot of humor involved. On days when someone forgot to bring their Fitbit, an image would circulate of a sad puppy on a leash lying flat on the sidewalk, captioned with the words: ‘When you forget your Fitbit, steps no longer matter.’ And Fitbit chargers would be held for ransom. Things like this made the workday more fun, more playful.”

But beyond making us laugh, tracking steps can also make us more grounded, experts say.

“Stress happens when we feel like things are happening around us over which we have no control,” said Alexander J Skolnick, PhD, an Emotion and Health Psychologist and Assistant Professor at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia. “Getting to 10,000 steps a day is one way to gain some control, and to make sure something goes right.”

When so many goals — personal, career, family — are long-term and oftentimes overwhelming, simply reaching 10,000 steps can feel like a blessedly achievable target.

“I’ve been studying a lot lately,” said Carol Spina, 38, a native of Galloway Township, New Jersey and former grade school vice principal who is changing the direction of her life by working toward a career as a financial advisor. “My Fitbit reminds me to move — to get my head out of a book and just breathe.”

The Obsession

But too much of a good thing is not always a good thing, and there’s a dark side to step tracking. When people live and die by an elastomer wristband, it can drive them to do things some might call neurotic.

“I travel a lot for work,” Smith said. “Once, I got 3,000 steps on the back of an airplane, in the five-foot area between the two restrooms. It was a route I flew often, so I knew the flight attendant. Another time, I fell asleep on a construction site where I’d been working 24/7. A security guard woke me up around 11:15pm, and I rushed to get in my remaining steps — about five or six thousand — before midnight.”

These stories are common among step counters. Take Crawford, the woman who feels like Rocky when she hits her count. She’s been known to jog in place before turning in at night.

“My husband hates it,” she said. “Our house is older, so there will be dishes rattling in the kitchen.”

Kraine knows the feeling.

“No one else in my family has a Fitbit, and they all think I’m crazy,” she said. “I like the challenge and I like completing a task, so if I have 9500 steps at the end of the day, I’ll walk around my living room while watching television. Last week my Fitbit broke, so I’m getting a new one tonight because it’s driving me crazy. I don’t walk as much without it, because it’s as though the steps don’t count.”

But beyond confusing or irritating family members, fanatical step counters run the risk of demoralization.

“There are pros and cons here,” said Brandon Alderman, PhD, associate professor of exercise psychology at Rutgers University. “Activity trackers may encourage some to be more active, but the successive non completion of the goal may have the opposite effect for a certain group and we need to be careful of this.”

A third of step counters will ditch the walking altogether within six months, while others will get so overwhelmed, they’ll resort to tricking a device into reaching the 10,000-step mark by, say, wrapping it around a working electrical drill, kitchen mixer, or ceiling fan — seriously. (Marching in place is one thing, but I think it’s fair to say if you’re enlisting the help of a pistol grip, it’s time to put down the Fitbit and back slowly away.)

As part of his research, Alderman has been thinking of ways to keep the novelty of reaching 10,000 steps from wearing off. “Whatever is fun and exciting about pursuing that goal in the first place, we need to harness it,” he said.

We may also need to learn to be kinder to ourselves, no matter our stride count.

“For a while, I felt really bad about myself if I didn’t get my step goal in,” Crawford said. “But if I’ve learned one thing over time, it’s this: it’s okay to listen to your body.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.