How school construction is changing due to security concerns

In this time of mass shootings, schools are feeling the pressure to make changes to how schools are constructed in an effort to keep intruders out.

Corl Street Elementary, in State College, is receiving extensive renovations, all done with safety in mind. (Emily Reddy/WPSU)

Martha Sherman has two kids at Mount Nittany Elementary School in State College. On a recent morning when she was dropping them off, office staff wouldn’t let her go beyond the front office. She wanted to walk her son Zane to his kindergarten class, but his school, like many others, has a safety policy that says parents can’t do that.

“He was just anxious about going by himself. His sister had run off, excited, and went to class so she couldn’t take him, which she normally takes him,” Sherman said. “And so, I thought ‘I’ll just take you to your classroom.’ And they said ‘No, we’ll get him there.’ ”

Sherman says it was tough on her son, who’s in a big school for the first time this year.

(Emily Reddy/WPSU)

“He’s very sensitive. And he’s a creature of habit,” Sherman said. “And so, you know, the routine changed. And so, he was just anxious.”

While she understands the need for safety precautions, Sherman says she thinks there could be some flexibility to make families feel more welcome. She’s also a criminologist at Penn State who questions whether locking down school buildings will even work.

“I don’t think it’s an effective tool for keeping the school safe. I think that if somebody wants to get into the school do harm, they’ll get into the school and do harm,” Sherman said. “But, the school has to try. And it is certainly easier for them to tell who belongs if not very many people belong.”

In this time of mass shootings, schools are feeling the pressure to make changes to how schools are constructed in an effort to keep intruders out.

School architect Jeff Straub was recently working on a renovation job at Corl Street Elementary in State College. Straub is certified in “crime prevention through environmental design.”

He showed off the giant multi-purpose room, which serves as lunchroom, basketball court and auditorium. Many walls here and throughout the building are made of glass. But Straub said a safety glazing makes that glass as sturdy as a solid wall.

Another feature the renovation adds is an entrance like the one at the school where Sherman takes her kids. Straub has been designing K-12 buildings for 20 years. He said having administrative offices at the front entrance of the school building is probably the biggest change in school design.

“One thing that you run into is in an older school – 40 years ago – very often you’d see the main office in the middle of the school, not at the main entry. The idea was you’d have the administration right at the heart of the school, could be easily accessible by the students,” Straub said. “Well, that created a security issue with essentially somebody enters the building and they have whole access to the facility.”

Other common safety changes include updated classroom door locks, security cameras and metal dividers that can be dropped to lock down parts of schools.

But Straub said building design alone isn’t enough. Sometimes what you need is good protocol. That could include training visitors not to hold the door open for the person behind them. Or making sure the main office has a packet of safety procedures. Straub said you don’t always need fancy safety gadgets, just knowing where to hide from an intruder can be enough.

“There’s a lot of people talking about wiz bangs and you know new blinds that well you hit a Velcro and you know it’ll close off the glass immediately,” Straub said. “But the comment might be ‘Well, you know what, if you have a window into a classroom and it’s a square classroom, well, do you have to block the glass when the kids can just go into the one corner and nobody can see them from the hallway?’”

Martha Sherman, the parent, said she doesn’t want her kids to feel like they’re in a prison. She likes that their school is bright and full of windows. This new one is, too. And in fact, Straub said construction choices, including using more glass, can cut down on issues that can sometimes lead to violence, like bullying.

“The problem that you have and very often in older buildings is, are there a lot of hiding places?” Straub said. “There’s this whole discussion about removing a lot of glass, but when you don’t have any views from the classroom to the hallway, well the staff, the teachers can’t be monitoring a hallway — if they can’t see through a solid wall — but if you have glass looking out into that space then they can monitor both those spaces at one time.”

Straub’s firm is currently working on three State College area elementary schools and the high school. He says safety features usually add from half a percent to a percent and a half to the total cost of a project.

Pennsylvania’s Act 44, enacted last June, gives school districts $25,000 each to improve safety. Many are hiring counselors or security officers, but Straub says many are also contacting his office for building improvements and safety assessments.

“The state police will do for free an evaluation of your building,” Straub said. “The problem is there’s a six to 12 month waiting list right now for that. And they don’t come in and do every school in your district; they will come in and do one building.”

(Emily Reddy/WPSU)

One of the more controversial building safety measures is metal detectors. Some parents, like Sherman, don’t want them. But Straub says they’re a good option for some school districts, if they have the personnel to run them correctly.

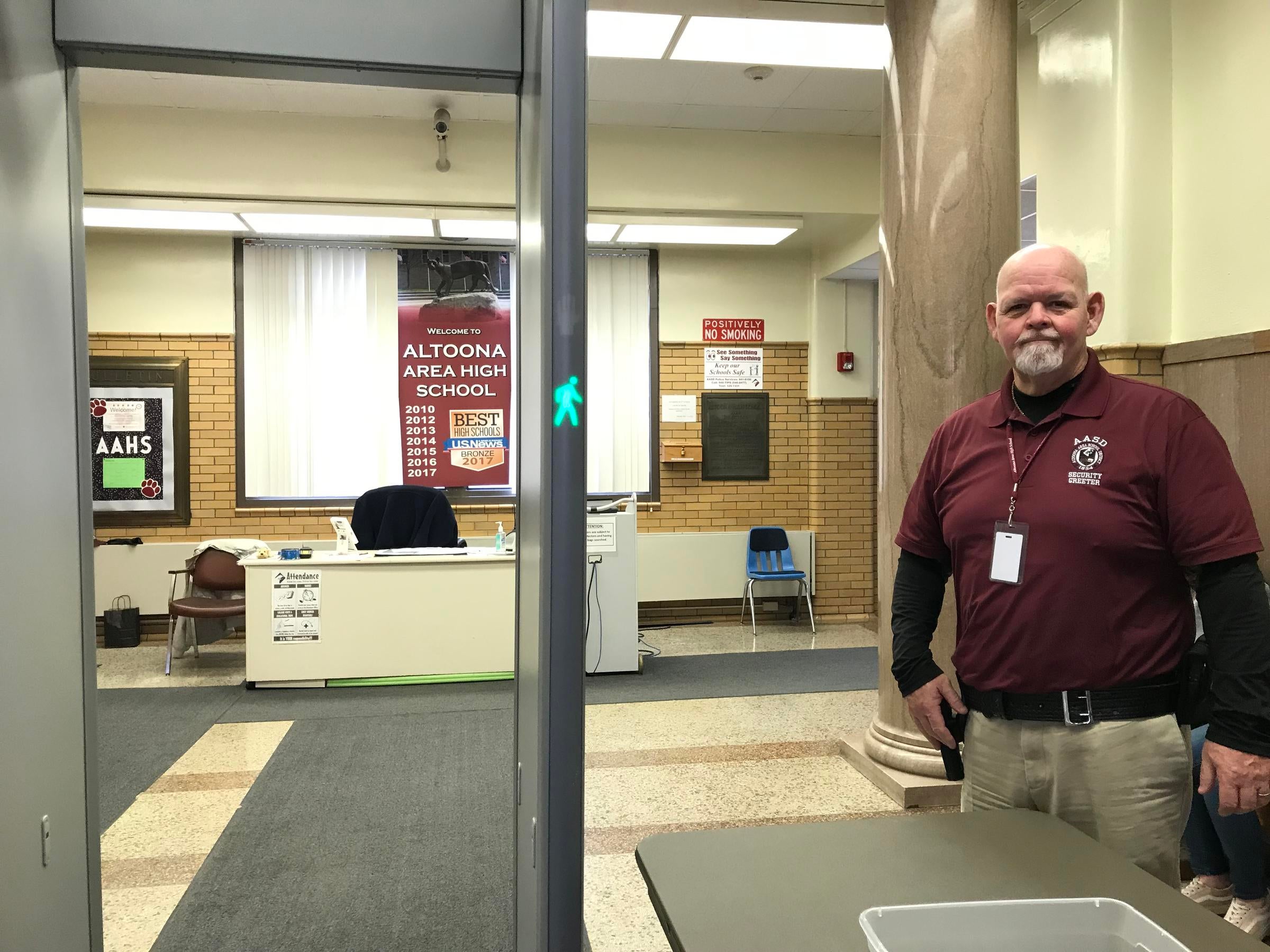

Students who arrive late at Altoona Area High School go through a metal detector manned by a “security greeter.”

Altoona doesn’t have all the students go through the metal detector every day, instead they put students through random metal detector checks. Assistant Superintendent Patty Burlingame said that was suggested by a security audit by the Pennsylvania Department of Education. She was the principal at the high school for 18 years and up until just a few years ago.

“When I was principal we would do the metal detectors at least once a marking period, but we’d do it if there was anticipated threat. We would just pull them out and we’d do them then,” Burlingame said. “We’d just do them randomly sometimes in the morning, just because.”

Police Services Director Bill Pfeffer said the high school first got the metal detectors about 20 years ago, around the time of the Columbine shooting. He hopes they never feel the need to put every student through a metal detector every day.

“I don’t want to say never. Hopefully it never does but I mean things change,” Pfeffer said. “Society’s changed since I’ve started his job.”

Burlingame said they’re now adding metal detectors at some of the district elementary schools.

“Well, I think it had to do with the most recent school shooting,” Burlingame said. “And the money was available. And one of the most recent shootings happened in an elementary, so that really prompted that as well.”

Visitors to the high school always go through the metal detector, have their ID scanned, and are escorted by security to where they need to go. In this old-style building, administrative offices are not at the entrance.

(Emily Reddy/WPSU)

But it won’t be that way for long. Altoona’s current high school was built in 1927, with an addition in 1972. It’s taken a lot of safety updates to make it secure. But soon the school district will replace it with a new $88 million high school with all the modern safety features built in.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.