How excited should Philly be about its growing office market?

In early 2016, the health care technology company IntegriChain moved to Center City from an office park near Princeton.

The suburban location had once made a lot of sense. In the 1980s, a network of office parks and mid-rise towers arose around Princeton with astonishing rapidity. Washington Post journalist Joel Garreau noted it as a model “edge city,” his catchy descriptor of the autocentric, exurban spaces that attracted much of the nation’s job growth in the late-20th century. (In his 1991 book on the phenomena, Garreau proclaimed cities like New York and Philadelphia “relics of a time past.”)

In many ways, the Princeton area should have still been an ideal location for a health-focused tech company. A large number of pharmaceutical companies are based there, many of which are IntegriChain’s customers. Proximity to an Ivy League school (and its attendant talent) could only be a boon, while both New York and Philadelphia are reasonably close.

But by 2015 IntegriChain was having a tough time attracting fresh recruits to their bucolic corporate campus. The big cities were close but not, it seemed, close enough.

“When we’d interview people, they’d say they were looking for a different area,” said Jennifer Fernandez, human resources manager at IntegriChain. “It was less people saying no, and more the applicant pool and the people interested to begin with that was kind of dismal.”

IntegriChain recognized that they had an especially hard time enticing young talent right out of school. They were hooked in to Drexel University’s co-op system, which seeks to connect undergraduate students with employers in their prospective fields while they are still working on their degrees. But from their offices near Princeton, accessible only by car, IntegriChain struggled to retain, or even attract, Drexel co-op participants.

“It’s difficult to recruit in Princeton, particularly for the type of talent we are looking for,” said Fernandez. “It wasn’t the hardest thing in the world, but it could have been be easier and that was part of the push to move us to Philadelphia, so we could have a larger talent pool.”

In January of 2016, IntegriChain plunged into the Philadelphia office market, opening a location in Center City. Five months later, they rolled up their operation near Princeton and moved all of their employees into the city.

They weren’t the only ones. In 2015 and 2016, Philadelphia’s market saw 1.3 million square feet of net new demand for office space from companies that hadn’t previously been established here. This is a remarkable shift for a city that’s largely seen the same companies shuffling from building-to-building for much of the last 50 years.

These entrants claimed blocks of office space were split between those coming in from the suburbs, at 600,000 square feet, and from outside the region at 700,000 square feet. The rate of growth slowed down this year. Only an additional 100,000 square feet have been generated so far in 2017, although there is 1.3 million square feet in the pipeline from the second Comcast tower alone.

These past few years of healthy office market expansion are part of a significant milestone in Philadelphia’s modern history. For the past half-century, jobs, as well as population, have been leaking out of the city and into the surrounding suburbs and then, later, exurbs and edge cities.

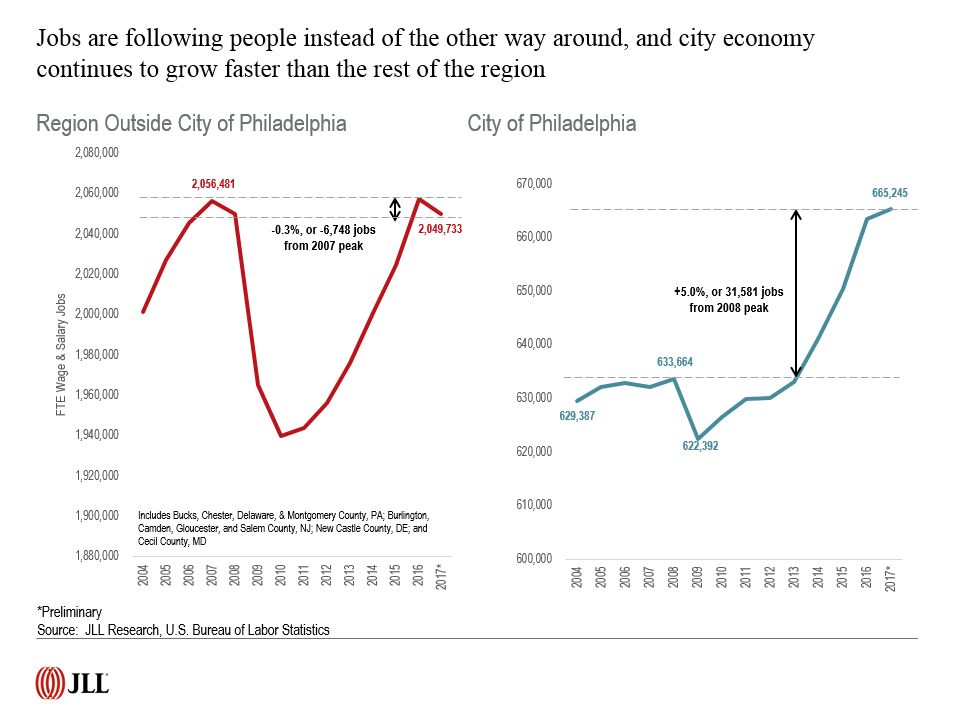

“What’s significant in this particular market cycle is that the trend of job movement out of the city has begun to reverse itself,” said Lauren Gilchrist, vice president and director of research for Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL). “What has happened since the [2008 recession] is that the city for the first time, really ever in its economic history, recovered above and beyond its pre-recessionary peak and the rest of the counties in the region have only just caught up.”

Outside Philadelphia, the rest of the metropolitan region still hasn’t quite matched its pre-recessionary 2007 peak: there are still 6,748 fewer jobs, or a deficit of 0.3 percent. (The metropolitan area is defined in this dataset as the four Pennsylvania collar counties, then New Castle County Delaware, Cecil County, Maryland, and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Salem counties in South Jersey.)

Currently, the city is five percent above its 2007 peak, with 31,581 more jobs today than ten years ago. Office employment in Center City and University City are a part of the story, even if the principal jobs engines remain universities and hospitals.

“One unique characteristic of this job growth is that Philadelphia finally saw new demand for office space, both from the net new perspective and from the organic growth of companies within Philly,” said Gilchrist. “This is really good news.”

The biggest leases of the past couple years include the 2015 Independence Blue Cross renting of 228,000 square feet at 1900 Market Street, across the street from their old headquarters, which allowed them to move many of their suburb-based employees downtown. In late 2016, Cambridge Innovations Center leased about 150,000 square feet in 3675 Market (which is still under construction), marking the Massachusetts based company’s first foray into the city. In early 2017, Vanguard signed a lease at 2300 Chestnut Street for 15,000 square feet for a satellite office focused on innovation, where hundreds of applicants applied for just 20 jobs. In 2015, the American Bible Society moved their headquarters from the current New York location, leasing 100,000 square feet in Old City.

But it’s too early to say that the City of Brotherly Love has bested its suburban brethren. Many of the region’s other counties still offer genuine competition and most of the region’s corporate headquarters are still based in the sprawl. Philadelphia offers just 45 million square feet of office space, compared to to 54 million square feet in the city’s Pennsylvania suburbs alone. Northern Delaware and South Jersey each have between 14 and 13 million square feet apiece.

“The trend is really real, but the interesting thing is that it isn’t a full-scale headquarters relocation,” said Gilchrist. “It’s what we would call a “gateway office.” We worked on some transactions where companies dipped a toe into the market to see how a city presence affects their workers but without having to commit to moving a full-scale headquarters downtown.”

That’s a meaningful caveat for a central city that, for all the excited talk about revival, still hasn’t seen anything like the corporate interest or job growth of wealthier neighbors like New York and Boston. In their annual report this year, Center City District (CCD) reported that only 26 percent of the region’s jobs are inside the city limits, in contrast to 30 percent in 1990. Finance and information sciences jobs, which CCD describes as “prime growth sectors for most 21st century cities,” have fallen by 40 percent since 1990.

Using 1970 as a baseline, just before the “edge city” trend began in earnest, the major Northeastern cities have both suffered job flight and then fully rebounded. But, despite the recent positive trends, Philadelphia hasn’t gotten anywhere close to fully bouncing back, whereas New York’s total employment is 12 percent higher than it was in 1970, Boston enjoys 21 percent more jobs, and has D.C. a whopping 24 percent more. In Philadelphia, meanwhile, there are still 25 percent fewer jobs today than there were the year before Frank Rizzo was elected mayor.

The Center City District and many other fixtures of the business community have long blamed labor costs and high taxes for making Philadelphia uncompetitive. But the city’s much maligned wage tax has been wound down for the past 20 years and, according to Fernandez of IntegriChain, hasn’t proved much of a detriment to newcomers.

“I was expecting to have to talk people through the wage tax again, but it hasn’t come up very often,” said Fernandez, referring to the process of hiring for jobs in the new Philadelphia offices.

That hasn’t always been the case. When she worked at a consulting firm in 2011 and 2012 it came up frequently.

“When I was recruiting then, there were a lot of people who would talk about the Philly wage tax like it was this horrible burden and would negotiate their salary around it,” said Fernandez. “Maybe because a large number of people [at IntegriChain] commute from New Jersey or already live in Philly we haven’t had to have that discussion.”

Fernandez says it’s about what Philadelphia offers, despite quirks like the wage tax, that few other places can.

“More people are looking for the work-life balance,” said Fernandez. “In terms of the commute it’s better because you don’t have to worry about driving. Then once you get there the atmosphere of being in the city is much more enjoyable than being in an office park.”

That sentiment has been going around. At an April meeting of the Center City District’s membership, one of the city’s most influential policymakers said Philadelphia should embrace its high cost reputation and work to maximize what it can offer that others cannot.

“The suburbs are cheaper, cleaner, safer, but Philadelphia has something people want,” said John Grady, president of Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC). “That has not always been the case. We aren’t a low-cost city and we shouldn’t compete on that basis if we can avoid it. We need to make it worthwhile to pay the added costs.”

Part of what Philadelphia can offer that its big neighbors elsewhere on the East Coast can’t are the benefits of a big city — restaurants, nightlife, culture, mass transit, walkability — without the immense cost of housing which encumber almost every other coastal city with similar amenities.

Philadelphia’s suburban competition is well-suited to try and beat the city at its own game. The most expensive office markets in the region are in places like Radnor and Conshohocken, which are relatively dense, relatively walkable, and located along regional rail lines. But given how SEPTA’s regional rail network centers on Philadelphia, even these older suburbs still can’t offer the same level of of easy, non-car commuting that the city does, forcing workers who don’t live here to brave Schuylkill Expressway and Blue Route traffic.

Gilchrist says that part of the reason for the recent expansion of office space in the city is precisely that huge swathes of those who live in Philadelphia have to commute to the suburbs for work. The highways leaving town are notoriously crowded on weekday mornings. Employers eager to cater to urban talent can be sure of winning hearts and minds by cutting a congestion-clogged commute to King of Prussia.

“Companies are trying to overcome the reverse commuting problem we have,” said Gilchrist. “If you get on the Schuylkill Expressway and head west at 7:30 you are having more trouble than you would be if you were coming into Center City.”

At least in public, city policymakers, civic cheerleaders, and business leaders are sanguine about Philadelphia’s urban edge. But the future remains uncertain. What if the Trump administration’s zealously anti-immigrant policies make Philadelphia’s population start shrinking again? What if denser suburban jobs hubs manage to outcompete the city on its own terms, especially if crime seriously increases again? What if, as everyone always fears, Millennials with resources give up on trying to make Philadelphia’s school system work for them, and retreat to suburban school districts like their parents did?

Reached for comment earlier this year, Grady reaffirmed his comments to the CCD membership and said that even the schools question wouldn’t necessarily doom Philadelphia’s nascent job growth. Even if the worst occurs, and professional-class Millennials leave the city, that doesn’t mean job growth would necessarily stop, too. Even in the context of potential population loss, a growing city jobs base would help shore up Philadelphia and its tax base.

“It’s more than just a fad, it’s the way people want to work,” said Grady. “Separately, Philly has become a place people want to live as well. Whether that trend comes or goes will be based on neighborhoods or schools or quality of life. But I think the decision about work is not necessarily the same decision.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.