Homegrown Middle Class: Finding New Money

To John Kromer the city’s persistent poverty is best tackled at the neighborhood level. In a four-part series of commentaries Kromer, an urban housing and development consultant and former city housing director, is exploring different policy interventions the next administration can deploy to reduce poverty, stabilize neighborhoods, and finance anti-blight work. In this second installment, Kromer describes one possible source of funding for this work.

USE MY PROVEN STRATEGY TO MAKE HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS IN TODAY’S LUCRATIVE TAX FORECLOSURE MARKET! Sound like one of those infomercials on late-night TV? Actually, there’s now a way that the public sector can become a more active participant in tax-foreclosure sales and, by doing so, make money that could be used to finance key elements of anti-blight programs and neighborhood stabilization policies.

You’re probably aware that when a tax delinquent property is sold at public auction, the money that’s collected from the winning bidder is used to pay the taxes that are owed to the city and school district, as well as to fund expenses associated with the sale. But when the winning bid amount exceeds the total cost of meeting these obligations, what happens to the money that’s left over?

That remaining money doesn’t get transferred to the city’s general fund or the school district’s budget. Instead, state law requires that these funds be distributed to private parties—a mortgage lender, a credit card company, or a private collection agency, for example—that have filed liens on the property. Any money that remains after lienholder obligations have been satisfied goes to the party whose property was auctioned off—the now-former property owner whose failure to pay taxes was the cause of the tax sale. But Philadelphia has a new opportunity to capture more proceeds from tax-delinquent property sales and target this money property stabilization and anti-blight work.

A New Opportunity & Potential Financial Benefits

The Buy/Resell Strategy, Step by Step

- After reviewing a list of addresses being processed for the next tax sale, the land bank identifies a number of higher-value properties—properties located in relatively strong real estate markets–that it wishes to acquire through direct purchase, rather than through competitive bidding at the tax sale.

- Prior to entering into each buy/resell transaction, the land bank researches the ownership status of each property in order to avoid acquiring occupied properties or capturing net tax sale proceeds that would otherwise be paid to homeowner-occupants.

- As the purchase price for the properties that it selects for acquisition, the land bank agrees to pay an amount equal to the required minimum bid price that tax sale administrators established for each property.

- The land bank’s intention to acquire the properties is disclosed in all of the advance advertisements, notices, and filings that have to precede the tax sale.

- As soon as the tax sale opens, the land bank is declared owner of the properties. At that point, the land bank has the ability to discharge most or all of the public and private liens associated with each property.

- Then the land bank immediately offers its newly-acquired properties for sale—either at the same tax sale auction, or at a separate auction that begins right afterward.

- The properties are sold to the winning bidders.

- Sales proceeds are used to pay the back taxes owed to the city and school district, plus sale expenses and a service charge for the land bank’s role in the transaction. The remaining funds then become a source of financing for the new neighborhoods policy.

A provision of Pennsylvania’s 2012 land bank legislation would enable the Philadelphia Land Bank to make money by purchasing higher-value properties listed for a tax sale (by exercising what is, in effect, a right of first refusal), clearing the liens associated with these properties, selling them at auction, and using the sales proceeds to help fund a new neighborhoods policy.

Here’s an oversimplified explanation of how it could work. The land bank buys a property at a relatively low price, clears the liens, sells the property for what is likely to be a substantially higher price, pays the back taxes, and then uses the remaining sales proceeds to help fund the city’s policy. A more detailed description of the process is shown in the sidebar.

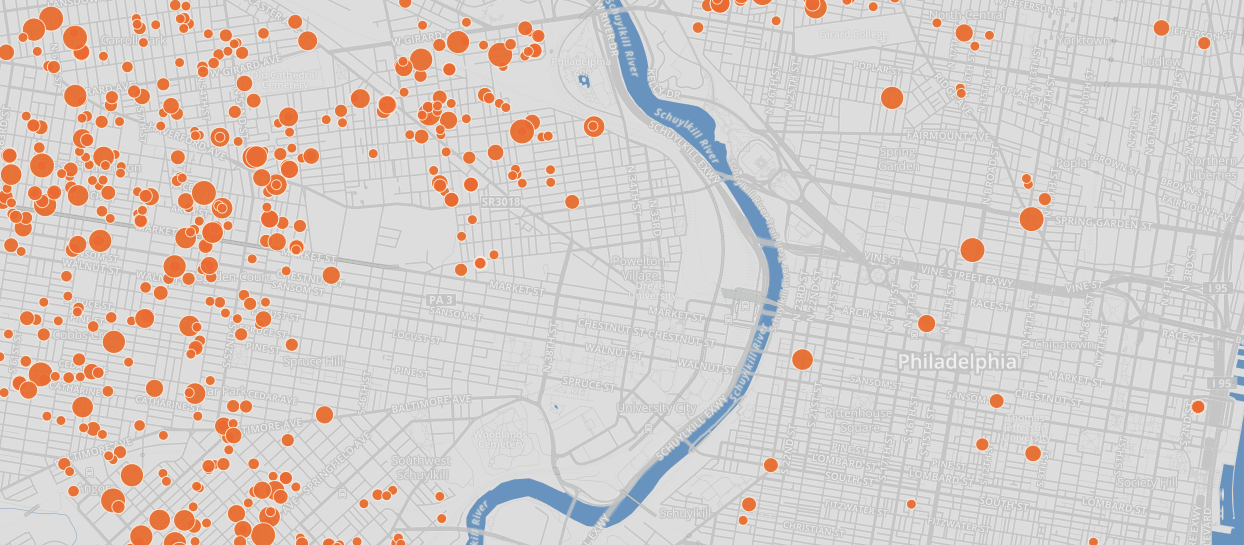

How much money are we talking about? No one knows, because no one has studied the data associated with the thousands of properties that have been processed for tax sales in Philadelphia in recent years. But an analysis of a June 2014 Berks County tax sale provides an interesting frame of reference. At that tax sale, the seven highest winning bids generated a total of $419,000. Following the sale, $152,765 was used to pay sales expenses and delinquent taxes, leaving a balance of $266,235. So a Berks County land bank that employed the approach I’ve described could have taken from the tax sale more than a quarter of a million dollars to finance anti-blight initiatives in the City of Reading and elsewhere.

How might this approach work in Philadelphia? I recently reviewed online data from two tax sales held in 2013. Of the 91 properties sold at these two auctions, all but one received winning bids that exceeded the required opening bid price. Although the minimum bid price assigned to each property may not be the same as the amount of taxes owed, it’s likely that (as in the Berks County sale) money was left over after the tax obligations associated with a number of these properties were satisfied. For many properties in the two Philadelphia tax sales, the winning bid was more than $10,000 greater than the opening bid price; for one property, the winning bid was $100,000 greater than the opening bid price.

I also visited the Sheriff’s Office and reviewed data for one randomly selected property from each of these two sales. I found that $55,000 was left over after tax obligations associated with these two properties had been met and sales expenses had been paid–$55,000 that the Philadelphia Land Bank (if it had existed at that time) could have earned by buying and reselling just two properties.

After acquiring and reselling these two properties, the land bank could have paid itself a ten-percent commission and still have had enough money left over to finance the completion of critical major systems repairs at five homes through the city’s Basic Systems Repair Program. Could the land bank’s managers have achieved comparable results with nine other properties sold at each of these two sales? If so, they would have made enough money to pay for fifty BSRP cases—or enough to fund the land bank’s 2015 operating budget.

Would the Philadelphia Land Bank be able to extract a quarter of a million dollars from a tax collection sale, as a Berks County land bank might have done in connection with the June 2014 tax sale? A more comprehensive analysis of past years’ Philadelphia tax sales would provide the information needed to assess this potential opportunity. So why not complete the analysis now? We might learn that the land bank could make even more.

This land bank buy/resell strategy (variations of which are already being used by land banks in other states) would not create any disadvantages for the most important participants in the tax sale process. In this approach, all the tax obligations would be paid, none of the properties would be withheld from a public auction, and the land bank would avoid incurring property maintenance expenses because it would sell the properties immediately after acquiring them. The two law firms that assist the city in processing tax sale cases—Linebarger and GRB—are paid a percentage of taxes collected prior to or as a result of the tax collection sale. Because the sales proceeds of properties bought and resold by the land bank would first be used to satisfy tax obligations, the law firms would continue to be compensated, as provided in their contracts.

But isn’t this strategy unfair to private lienholders—for example, the lending institution that holds a second mortgage on a particular property? Not really. These private lienholders are all notified of the tax sale in advance. If they’re really concerned about preserving their equity interest in that property, all they have to do is pay the back taxes, and the sale is off.

Are We Ready to Innovate?

How could this innovative approach be implemented in Philadelphia, given the serious problems associated with the administration of the Sheriff’s Office, as reported by the City Controller and others? Despite these problems, the city is reasonably well positioned to put this plan into practice.

- The city administration and the two law firms that process tax sale cases for the city already cherry-pick tax delinquent property lists in order to ensure that as many higher-value, readily marketable properties as possible are included in each tax collection sale. The Sheriff’s Office is not directly involved in this property-selection process.

- With the addition of a single, brief paragraph—which might be only one sentence long–the advertisements, public notices, and lienholder notifications that precede the tax collection sale would provide adequate notice of upcoming land bank buy/resell transactions.

- The tax sale auction would open with an announcement of the properties that had been acquired by the land bank. Otherwise, the auction process would be unchanged.

- Because a land bank can’t exercise what I’ve referred to as a right of first refusal unilaterally, the land bank, the Law Department, and the Revenue Department, along with the Sheriff’s Office, would execute a memorandum of understanding with the land bank in order to formalize the process. Although I can’t predict how readily such an agreement could be executed, the fact that none of the parties involved would have to make a financial sacrifice or significant commitment of administrative resources suggests that it might not be that difficult.

Now for the Hard Part

The biggest potential hurdle: the Sheriff’s Office would need to demonstrate the capability to complete the post-sale distribution of funds reliably. The administration of former Sheriff John Green was unable to account for millions of dollars of funds that should have been distributed following tax sales that took place during his tenure, and the FBI seized real estate files from the Sheriff’s Office in 2013, during the current administration.

These serious problems need to be resolved to the public’s satisfaction—and what better time to resolve them than during this election year? The Nutter Administration has indicated that the current Sheriff’s administration has made “a Herculean effort” to improve the functioning of the office. So why not take advantage of this opportunity to demonstrate that the office now has the capability to distribute sale proceeds efficiently and reliably?

Later in this series, I’ll describe other ways of finding new money to support a neighborhoods policy. Pursuing the buy/resell strategy wouldn’t generate all the financial resources that would be needed to support such a policy, but it could provide a significant amount of new money–money that isn’t subject to restrictions and limitations such as those associated with federal grant programs.

As described above, this approach would be relatively easy to administer, once working relationships had been established between the Philadelphia Land Bank, the Sheriff’s Office, and the other city agencies that participate in the tax sale process. The sooner these working relationships are formalized and operationalized, the sooner we can start making money to provide new benefits to Philadelphia neighborhoods. Can we get ready to do this now?

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.