After half-century, Chuck Close photographs make Philadelphia debut

"Chuck Close Photographs," now at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, is a large and meaty show with 90 images created over 50 years.

-

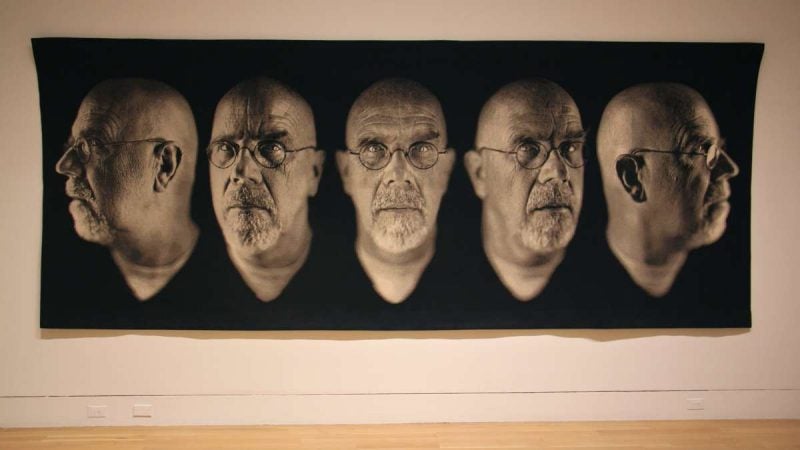

The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts is hosting the first major exhibition in Philadelphia of the photographs of Chuck Close. The 183-inch-long ''Self-Portrait/Five Part'' was made in 2009. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

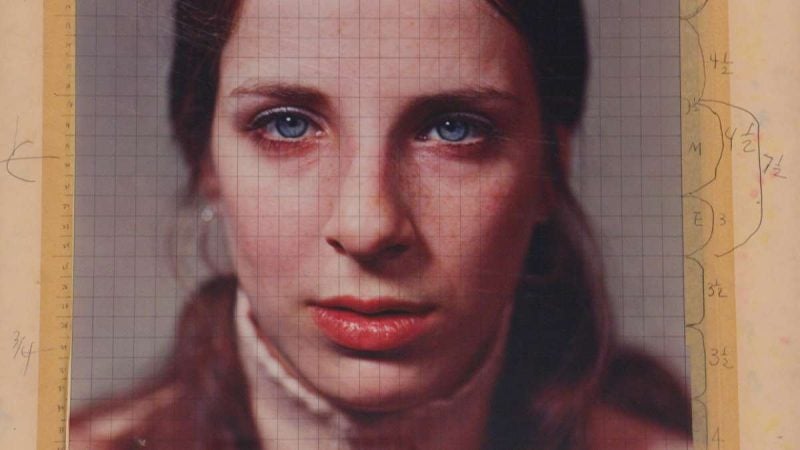

By drawing a grid on the photographs he called ''maquettes,'' Chuck Close could transfer the image to monumental paintings. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

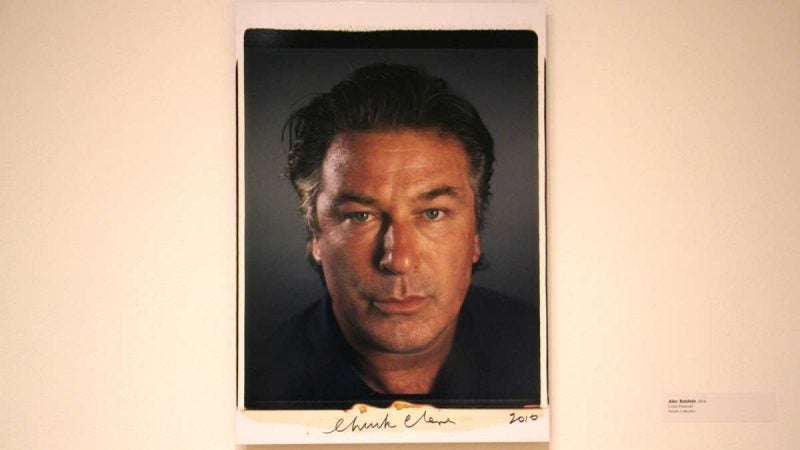

A color polaroid of Alec Baldwin made in 2010. Chuck Close called his portraits ''heads'' to make clear that he was not trying to interpret or convey a subject's personality. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A pigment print of artist Kara Walker from 2008 and a maquette made in 2010. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The Polaroid triptych ''Chrysanthemum'' is juxtaposed with the five panel ''Bertrand II.'' (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Curator Terrie Sultan stands before Chuck Close's ''Laura I,'' 1984. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

One of the most prominent living artists in the U.S. right now — Chuck Close, 77, with a career spanning six decades — has never had a major show in Philadelphia.

While “Chuck Close Photographs,” now at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, is a large and meaty show with 90 images created over 50 years, it is not quite the definitive retrospective Close might deserve. But it comes close.

“When we became aware that there had never been a major Chuck Close exhibition in Philadelphia, we saw that as an opportunity to fill that hole and provide the local community with an exhibition of this singular American artist,” said museum director Brooke Davis Anderson. “When you have to list the top 20 artists working in America today, Chuck is at the top of most people’s list.”

Close has work in the collection of nearly every major museum of contemporary art. He has painted President Clinton, and photographed Barack Obama. He sat on the President’s Committee for Arts and Humanities until earlier this year, when he and several other committee members resigned in protest over President Trump.

The exhibition makes the case that it all started with photography.

“Maybe there was a sense of denial in the early years, that the photographs were just about foundations for paintings,” said curator Terrie Sultan. “But in going back and looking at how interesting and beautiful they are, he’s realized it’s really part of his life as an artist.”

Back in the 1960s, Close made a big splash with “Big Nude,” a monumental-sized painting of a reclining woman. He was able to get an extreme level of detail by using photography — he took a series of close-ups of each part of the body, then outlined a grid over each image, and transferred each square in the grid to a 22-foot canvas.

Later, he would that process — preparing paintings with grids based on photography — to paint enormous portraits, for which he has become well known.

But don’t call them portraits.

“They weren’t intended to capture a perfect moment, or a time, or a place, or a personality,” said Sultan. “He uses the word ‘dumb’ to describe it — not meaning stupid, but not inflected. There’s no sense that he’s, like, ‘smile big,’ or ‘exude life.’ He would never say that to someone when taking a picture.”

Sultan made this exhibition for the Parrish Art Museum in the Hamptons of New York where she is director. “Chuck Close Photographs” has visited five cities, Philadelphia is the last.

The exhibition is mostly large-format Polaroids, an instantaneous format Close prefers because it allows him to consider the image in collaboration with the model, still in the room. The show highlights Close’s obsession with process; some of the faces looking out from the walls of PAFA are pocked with color-correction instructions and mounted with masking tape.

“There’s a new kind of freedom to look at works that reveal a creative process being an artwork in and of itself,” said Sultan.

Close — who has a few good quips under his belt — once said “inspiration is for amateurs.” He has a strong belief that making work begets ideas for more work. The exhibition includes his forays into historic photographic processes of daguerreotypes and Woodburytypes — 19th-century techniques that are fantastically labor intensive.

Sultan said Close uses photography as a way to dispassionately map the human face, out of necessity. He has a facial blindness condition — prosopagnosia — that does not allow him to recognize human faces. A flattened photograph of a face is easier to read, for him, than encountering a face in real time and real space.

“People’s faces are always in motion,” Sultan said. “If you’re talking to him, and you raise your eyebrows or smile or something like that, it completely changes the map of your face, and he doesn’t recognize it.”

While many people will see in his work faces of a famous personalities — such as Alec Baldwin or Philip Glass — Close is instead interested in the human face as a landscape of visual complexity.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.