Working in isolation for 10 years, Philly artist reveals his army at Grounds for Sculpture

Clifford Ward has quietly crafted two dozen African fantasy warriors. They are the centerpiece of his first exhibition in a decade.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

For 27 years, Clifford Ward has maintained a studio at Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey, an hour-and-a-half commute from his home in Philadelphia’s Old City via two trains and a bus.

“I just do work,” he said. “When I go to Philly, it’s just to sleep and watch TV.”

The mixed media sculptor last showed his work in 2013 at Fresno City College in California. Since then, few people were aware of what he was doing.

“I was very reclusive,” he said. “People are questioning, now that I’m out in the spotlight: ‘Where have you been all these years? We never see you. We haven’t seen your work.’”

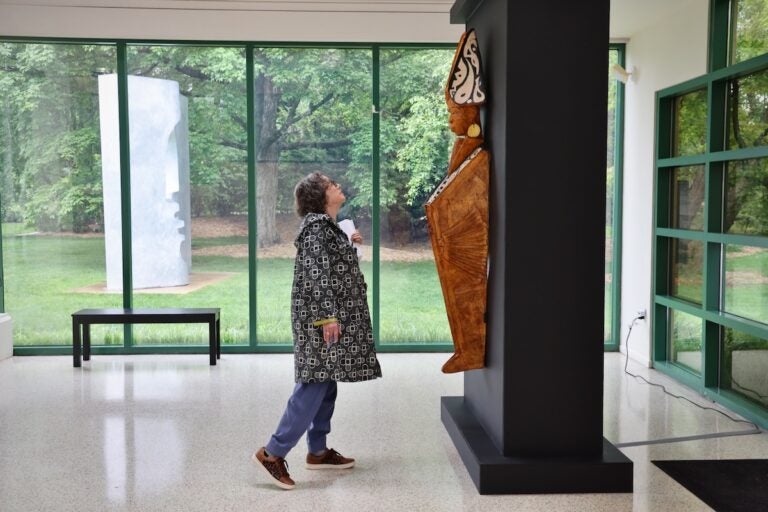

Ward has been quietly building an army. “Animism” is a series of 24 life-size tribal warriors standing at attention. Some are draped in regal robes. Some have animal heads. They all carry poles resembling spears.

The army is the centerpiece of “Clifford Ward: I’ll Make Me a World,” an exhibition of 50 works the artist has been making over the last 10 years. A smaller version of the show, “I’ll Make Me a World, Prologue,” was shown at Artworks in Trenton earlier this spring.

A pan-cultural fantasia

Ward borrows liberally from various cultural traditions, from pan-African tribalism to Maori tattoos to Australian Aboriginal symbolism to Egyptian hieroglyphics. Inspired by the ancient Terracotta Warriors of China, his fantasy fighters appear to be of a non-specific African nation.

“When exploring Clifford’s studio for the first time I was blown away, amazed that I hadn’t been more familiar with the practice previously,” said curator Noah Smalls. “Right away, I saw a transcendence of the Afrofuturist theme, which is so prevalent right now in the arts. It very much intertwines fantasy and history with our present realities.”

Some of the “Animism” figures wear Elizabethan ruff collars, giving them a regal flair from an incongruous European costume tradition. The last two figures Ward made, in the rear of the troop, wear slave collars: iron bands with four hooks protruding about 16 inches.

The iron cross around the neck was designed to snag brush and branches if an enslaved person attempted to escape. As a sculptor, Ward is attracted to the aesthetics of crosses as strong visual shapes. He said when he put the collar on a figure clothed in fine robes, it resembled a ritual adornment.

“I watched it progress into something totally different. It transcended the collar and became almost deified,” he said. “I want people to talk. I want people to ask what it was and to learn something about American history. It’s such a horrible, barbaric device, but it creates a very strong visual and a very strong narrative to go with the piece.”

Other works have softer origins. A series of 98 small paintings on wood are hung in a grid hugging a curved wall of the exhibition space. “Miracle of the Smiling Mom 98” represents every year of the life of Ward’s mother, who died in 2017 at age 98.

“My mom was one of the biggest benefactors and influences in my art,” he said. “She always would tease us about writing a book called ‘Miracle of the Smiling Mom.’ She was joking, but I think she really wanted that. I don’t write so I decided to do an installation dedicated to her.”

Ward made a pair of masks with empty eye sockets covered in abstract painted glyphs and whose “Donnie Darko”-like twisting horns are wrapped in a leopard pattern.

The two masks are “Ode to George I” and “Ode to George II,” in homage to a beloved antelope at the Philadelphia Zoo.

“My friend worked for the zoo and took me behind the scenes and showed me a skull of this animal she was very fond of, George,” Ward said. “I just love the horns.”

George, a sable antelope, lived at the zoo for 20 years before passing away in 2005. His remains were preserved to be used for educational programs.

“That’s a tribute to George,” Ward said. “ Thank you, George, for your horns.”

Ward’s history

Ward came late to artmaking. At 40 years old he left his career in the publishing industry to pursue sculpture. In 1997, he landed an apprenticeship at the Johnson Atelier, a sculpture fabrication company founded by artist Seward Johnson, who also founded Grounds for Sculpture. Ward never left. He moved through the apprentice program, became staff and ultimately secured one of the studio spaces on the campus. Ward no longer works at the atelier; instead, he teaches at the Center for Creative Works in Ardmore, Pennsylvania.

One of his exterior works was acquired by Seward Johnson, “Jubilant Dancer,” to be part of Grounds for Sculpture’s permanent collection. But he has never had his own exhibition there.

“We’ve been watching this body of work develop over the last 10+ years and he’s incredibly disciplined about not showing it,” said GFS Executive Director Gary Garrido Schneider.

“He had the discipline to forgo opportunities to show the work piecemeal until he finished the series,” he said. “That’s really impressive, to watch an artist have that kind of vision.”

“Clifford Ward: I’ll Make Me a World” will be on view until January 2026.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.