A scrap of cloth found at Goodwill turns out to be part of American history

A Virginia man bought a tattered piece of cloth claiming to be part of George Washington’s war tent. It’s now in a Philadelphia museum.

Richard "Dana" Moore discovered a scrap of George Washignton's war tent on Goodwill. He and his wife Susan Bowan loaned it to the Museum of the American Revolution. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Goodwill is not just a chain of thrift stores, but an online auction site of oddities.

The select donated items up for bid are often not dissimilar from the random things you might find in a brick-and-mortar Goodwill store, like a rhinestone clutch bag from The Limited ($7.50), an oversized belt buckle from the Society of Explosives Engineers ($9.99), or a certified authentic Thomas Kinkade painting of a scene from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast ($41.00).

Richard “Dana” Moore is used to digging. The amateur collector hunts for historic military artifacts online and in the field with a metal detector. When he has a feeling he is getting close to something, he listens to his gut.

About two years ago, he was searching through Goodwill’s listing of historic documents and stumbled upon something totally unexpected. It was not a document at all but a small piece of fabric about six inches long, claiming to have been torn off a field tent used by General George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

“There was no proof. There was no documentation saying this is authentic,” remembered Moore.

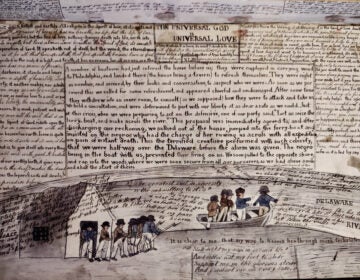

The only authentication it had was sketchy, at best: a hand-written note explaining the fragment was acquired in 1907 at the Jamestown 300th anniversary exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. The note was fixed to the textile with a rusty sewing pin.

One part of Moore’s brain was thinking about the sad people he has seen on the PBS program Antiques Roadshow when they are told they bought a fake. Another part of him – the gut part – was excited.

“It was a heart thing,” he said. “I was, like, ‘This can’t be.’ And then I thought, ‘OK, I’m doing this.’”

After a small bidding war Moore won the cloth fragment for $1,300. He decided not to reveal that fact to his wife, Susan Bowen.

“I didn’t want to tell her because then she’s going to ask me, ‘Where’d you get that and how much did you pay for it?’” he said. “It’s hard for me to lie about that.”

Even after the fragment was delivered, he kept it under wraps until his wife’s son was home.

“He thought it was safer to show me when there was somebody else around,” Bowen said.

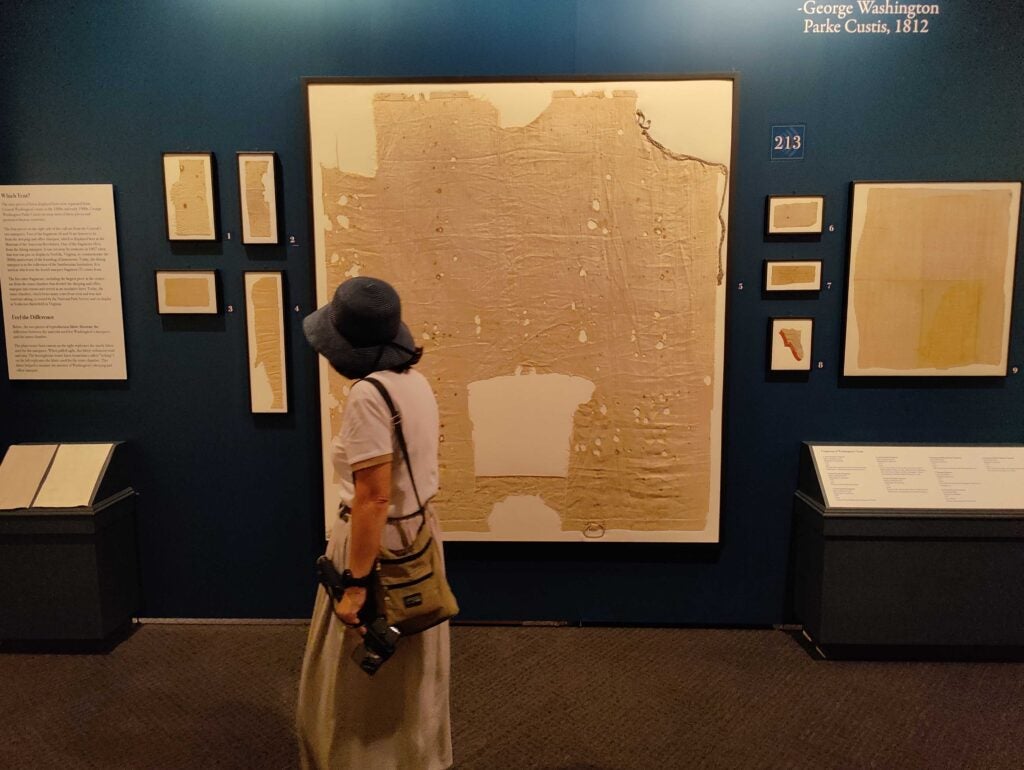

The piece of fabric turned out to be authentic. It is now on display at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia as part of his exhibition, “Witness to Revolution: The Unlikely Travels of Washington’s Tent.”

The fragment did not come from the museum’s tent in its centerpiece exhibition, but rather a dining marquee Washington used for meals and meetings during the Revolutionary War. That tent passed down through Washington’s descendants and was ultimately contributed to the Smithsonian Institution.

It went on display in 1907 in Norfolk, Virginia, for an exposition celebrating the 300th anniversary of Jamestown. A man named John Burns attended the expo and ended up taking home a piece of the tent.

It was neither the first nor last time someone would break off a priceless piece of history and put it in their pocket.

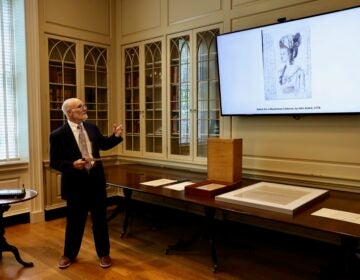

“We’re trying to figure out more about this person John Burns and his relationship to the exhibition,” said curator Matthew Skic. “We’re still actively trying to figure out more of the context surrounding this ‘borrowing’ of a fragment of George Washington’s dining marquee.”

Moore’s luck struck twice. When he and his wife reached out to the museum, Skic was already preparing “Witness to Revolution” with a display of tent fragments held in the museum’s collection and other institutions. He was more than eager to include Moore’s piece, the only fragment not owned by an institution. The museum’s conservationists gave Moore’s scrap an archive-level framing for long-term preservation.

For Moore, the scrap of Washington’s tent is more than a curiosity. The Vietnam War veteran who now works for the Department of Homeland Security can trace his ancestry to a soldier serving under Washington at Valley Forge. Searching for war artifacts is in his blood.

“I was looking for something cool. This is really cool,” he said. “I was over the moon.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.