Goodbye to Richard Goodwin, whose prose sang the promise of America

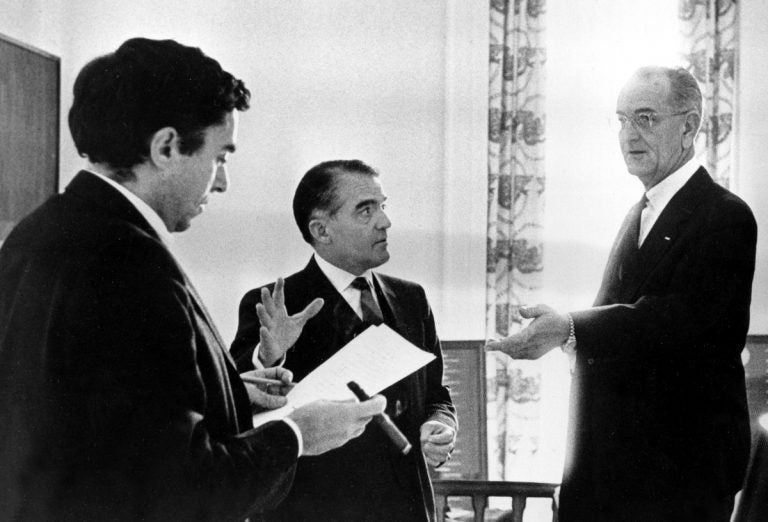

In this Jan. 12, 1966, photo provided by the White House, President Lyndon B. Johnson prepares for his State of the Union address with, (from left), Richard Goodwin, former presidential assistant called back from Wesleyan University to help on the speech, Jack Valenti and (not pictured) Joseph A. Califano, Jr. at the White House in Washington. Goodwin, an aide, speechwriter and liberal force for the Kennedys and Lyndon Johnson died Sunday, May 20, 2018, at his home in Concord, Mass. His wife, the historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, said he died after a brief bout with cancer. (The White House/AP Photo)

You’ve probably never heard of Richard Goodwin, who died Sunday at 86. But there once was a time when his unparalleled eloquence leapt from the mouths of presidents, a famous time in our history when his words summoned a nation to fulfill its promise.

For that alone we need to mark his passing. Today more than ever, we need to remind ourselves that past presidents didn’t sound like the most choleric dolt in the barroom. Thanks to Goodwin, a president successfully coaxed Congress to pass a law guaranteeing equal voting rights to African Americans (the opposite of vote suppression) by sharing the speechwriter’s prose-poetry on national TV:

“I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy … Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country. To right wrong, to do justice, to serve man. In our time we have come to live with moments of great crisis. Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues — issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression. But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation.

“The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation …

“This time, on this issue, there must be no delay, or no hesitation or no compromise with our purpose. We cannot, we must not, refuse to protect the right of every American to vote in every election that he may desire to participate in … We have already waited a hundred years and more, and the time for waiting is gone …

“From the window where I sit with the problems of our country, I recognize that from outside this chamber is the outraged conscience of a nation, the grave concern of many nations, and the harsh judgment of history on our acts. But even if we pass this (voting rights) bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause, too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it’s all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

“And we shall overcome.”

Goodwin wrote that 1965 speech for Lyndon Johnson on an eight-hour deadline. He was barely 30 years old (he called it “the restless, romantic energy of youth”), a working-class kid fired up by government’s potential for doing good. He once told me, when he and I met for lunch in the fall of 1988, that he’d sometimes devote as many as 36 sleepless hours to writing a speech — aided by drugs administered by a White House doctor who’d inject “an unnamed red liquid” into his shoulder.

His labors produced “The Great Society.” He coined the term. Before it was lost in the rubble of Vietnam, LBJ’s Great Society program gave us Medicare and Medicaid and federal aid to schools and other landmarks that today we take for granted. Goodwin was the one who framed its promise in a ’64 speech with sweeping historical context:

“For half a century we called upon unbounded invention and untiring industry to create an order of plenty for our people. The challenge of the next half century is whether we have the wisdom to use that wealth to enrich and elevate our national life — to advance the quality of American civilization … For in our time we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but toward the Great Society …

“The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time … It is a place where men are more concerned with the quality of their goals than the quantity of their goods. But most of all, the Great Society is not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work. It is a challenge constantly renewed, beckoning us toward a destiny where the meaning of our lives matches the marvelous products of our labor.”

Obviously, those ambitions for America have fallen short. But in the depths of our current dystopia, it’s well worth remembering that we still have the potential to summon the better angels of our nature, to envision an inclusive, egalitarian America through the power of words.

Goodwin had bouts of despair in later life. When I lunched with him at Rockefeller Plaza nearly a quarter century ago (I was profiling him because he had a book coming out), he said over his plate of linguini that America was suffering from “an accelerating infection of semi-literacy.” He lamented “the banality and emptiness in today’s political climate, the shrinking aims of political oratory.” He said, “People don’t expect to be told the truth, and that’s why they don’t pay much attention anymore to politics … The hopeless don’t revolt. The cynical don’t march.”

That was 1988. Imagine what he must’ve thought about Trump and the current American condition. But he also once wrote that there are times when “history itself” can be “bent to the just needs of humanity. I believe that still.”

As should we.

Goodwin may be gone, but this speech passage, from 1965, should bolster our resolve to rescue this country from the destructive clutches of Trumpism:

“(R)arely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.