North Philly’s industrious community creation

February 5, 2010

By Thomas J. Walsh

For PlanPhilly

The McDonald’s fast food empire is not universally considered a paragon of a green-minded, environmentally friendly corporate culture. But the charitable organization formed by the company’s founder, fed by those billions and billions of burgers sold over the decades, is these days in the business of serving up environmentally sound salvation.

The Salvation Army, that is, which in 2004 received a cool $1.5 billion from the will of Joan Kroc, heiress to the fortune of McDonald’s king Ray Kroc. Since then, the Salvation Army has been building on a comprehensive community center model established in San Diego, one that is changing the entire concept. The idea was to create a publicly supported town center in needy neighborhoods, with open space, gymnasiums, perhaps a library, a performing arts hall, even laboratories.

The model has since spawned six others, from places like Ashland, Ohio and Coeur d’Alene, Idaho to another big California city, San Francisco. All have incorporated aspects of the latest in green building technologies and techniques.

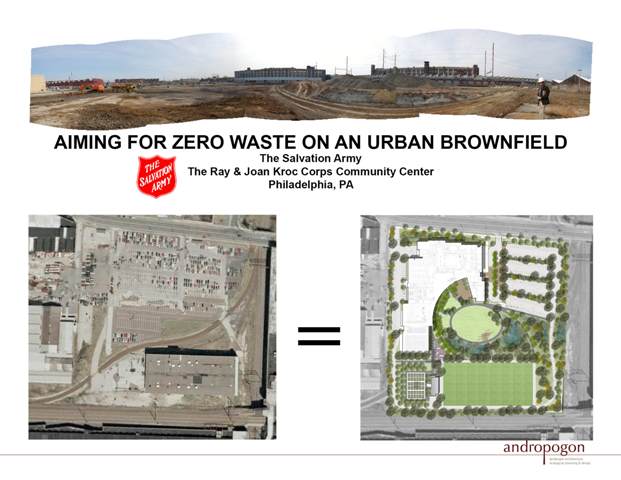

Now it’s Philly’s turn. By the end of 2010, one of the greenest developments ever undertaken in the city will be situated on Wissahickon Avenue near Hunting Park, bordering the Tioga / Nicetown and Germantown neighborhoods in North Philadelphia.

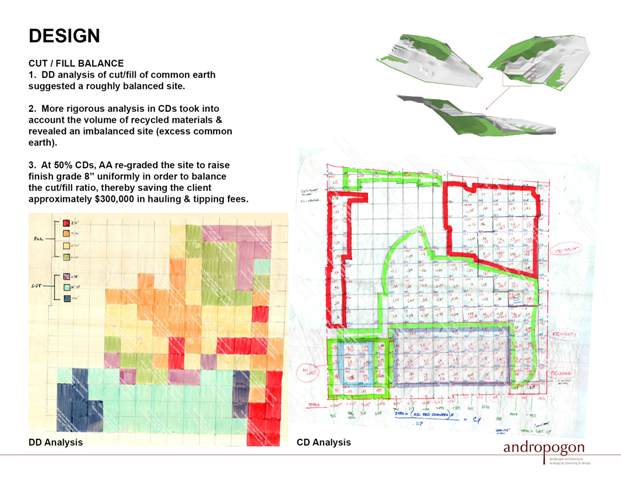

The 12.4-acre, $72 million brownfield site, with a 130,000 square-foot building, will be on a desolate parcel in the midst of one of the area’s poorest neighborhoods, but will be more akin to a high-end spa than a run-of-the-mill community center. Designed by two Philadelphia architectural firms, MGA Partners (the new building) and Andropogon Associates (site development and landscape design) on part of the old Budd Co. property, the original goal was “zero waste construction,” with all materials from a large parking lot and demolished warehouse to be re-used.

“It’s a unique and innovative project,” said Katherine Gajewski, the city’s director of sustainability. “It touches a lot of areas. It will add tremendous value.

“It also brings up this conversation of some of the larger former industrial landscapes that we have – looking to re-invent these spaces for updated and new uses. This is a great example of how you can go onto a property like that and do something really special.”

Retooling, filling in

Highlighting their partnership on the North Philly project, Andropogon and MGA are featured together in an exhibit opening Friday evening at the Community Design Collaborative called “Retooling Industrial Sites,” the third phase of the Collaborative’s “Infill Philadelphia” initiative, which kicked off in 2007 and has been focusing on industrial sites around the city. (The group held a charrette for planners, designers and architects in November that examined short-term industrial re-use.) The firms are among almost 40 that are being showcased through March 26.

“Our hope is to inspire policymakers, design professionals, developers – both nonprofit and for-profit – and the public at large,” said Beth Miller, executive director of the Collaborative.

The Kroc money came with a sort of rough site plan already in place, with direct stipulations from Joan Kroc’s will. The centers must be open to the public and used for family support, education, indoor and outdoor recreation, and cultural arts, in underserved communities. No one can be turned away from the facilities for financial reasons.

But even with the backing of a big-name, large scale developments have been rare since the second half of 2008 – for any kind of project, anywhere, let alone a nonprofit community center in a forlorn section of a Rust Belt city.

So it helped that the project was set in motion in the years leading up to the credit crunch, and that so much of the financing was in place from the start. In Philadelphia, things were also helped along by a reputable owner and developer, Conshohocken-based Preferred Real Estate Investments, and a tidy amount of tax credits at the ready for builders. The entire Budd site, stretching out over about 80 acres, sits within a Keystone Opportunity Zone.

The Budd plant, which used to turn out commuter train cars and automotive frames, was shuttered in 2002 after more than 80 years in business. Plans have varied from an enormous inner-city golf course to a Trump casino, but Preferred bought the property in 2004 with plans to make it a mixed-use business park: the Budd Commerce Center. Preferred’s market niche is acquiring and redeveloping abandoned industrial sites into office parks and hip apartments or condominiums. With a gleaming new Kroc center up and running within a year, Preferred could well have a feel-good success story to pitch to future investors looking to locate on the site.

“The economy actually helped us,” said Chris Mendel, Andropogon’s project manager for the Kroc Center. “We went to bid at close to the low point [in the recession], so they probably got low numbers from contractors who were very hungry for work. It certainly didn’t help the Salvation Army with its fund-raising, but I think they had most of their funding in place by 2006 or 2007, when this was really just a concept, and most of that came from Kroc.”

“The timing was just very fortuitous,” said Dottie Wells, business manager for the Salvation Army of Greater Philadelphia.

With funding for nonprofits so difficult, Miller said the Kroc gift helps make the Salvation Army stand out as a “’Cadillac’ of projects.’ “It’s another example of industrial re-use that can be done, and done well,” she said.

Mendel said a certificate of occupancy is due to be issued September 1 for the building, with an opening ceremony scheduled for October 15. It will be officially known as the Salvation Army Ray and Joan Kroc Corps Community Center.

The Malibu of community centers

There will be a fitness center in addition to the gymnasium on the site. Also taking shape is an aquatics center – a “family water park,” a warm-water jet pool, and a separate 25-meter “competition pool.” There will be a sliding scale for membership at the fitness and aquatics centers.

Wells said the new daycare center will feature early childhood education. A worship and performing arts space (the Salvation Army is a Christian organization) will seat about 300, with state-of-the-art sound equipment. A learning center will encompass a series of multi-purpose rooms, including a computer lab.

There will be other community meeting rooms as well, along with outdoor spaces for events and a central neighborhood green. That’s not including a 160-by-360-foot outdoor athletic field taking shape, with synthetic turf to facilitate year-round activities. Or the organic neighborhood garden.

“It’s all about health and wellness,” Wells said. “We’ll have classes on nutrition and cooking, and getting fresh produce available in the city.” The garden (about three-quarters of an acre) will help with job training, too, Wells said, in the food and landscaping industries, along with teaching neighbors how to start and maintain other gardens on the copious amounts of open spaces nearby.

A water hotel

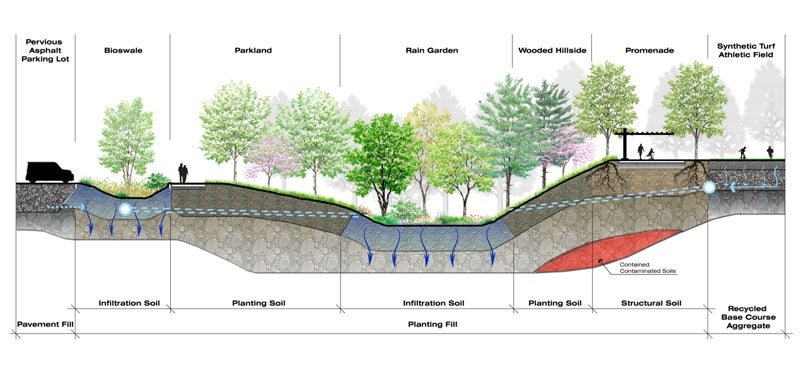

At the Kroc Center, storm and waste water will check in, but not much will check out.

“It‘s a real benefit to the city,” said Amy Stein, MGA’s project manager for the Kroc Center. “We’re really a cutting edge test site for the [Philadelphia] Water Department there, because all the rain water that hits our building we’ll be filtering naturally rather than mechanically. It does cost a little more money, but we like to think that the Salvation Army will own the building for a long time.”

MGA is working in association with Philadelphia-based PZS Architects on the building’s design.

The savings on the center’s water supply will be large and immediate, Stein said. Mendel believes that as construction and development increases in the coming year or so, green utilities will become more mainstream.

“I really hope that we’re not alone,” he said. “I can say we are trying our very best to make sure that this is one of the most forward-thinking integrated site and architecture work that’s framed around taking some of the new compliance requirements from the Water Department and pushing them even further.”

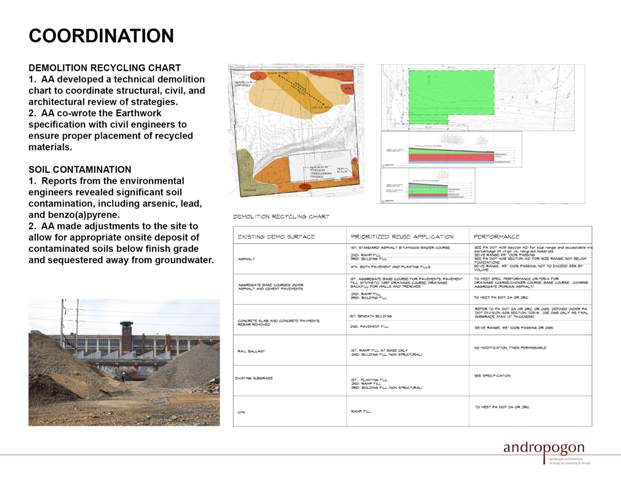

As for the original goal of making it a “zero waste site” – taking all the existing asphalt, concrete, rebar and foundation materials and re-using them so that none of it leaves the site – hitting 100 percent proved impossible, Mendel said.

“We found out there was a fair amount of contamination that had to leave the site,” he explained. “Also, once demolition had begun, there were other foundations that no one had anticipated, and that [material] had to leave the site as well. But I would wager that we re-cycled almost 90 percent of everything that had to be manipulated and encountered, in terms of surfaces.”

There was also a shell of a Budd warehouse still on the site, which was demolished. Its large I-beams, prized because of the recent high price of steel, were put back to work on the new structure.

“From a design perspective, the biggest hurdle we had to cross is trying to document, to traditional construction guys, how to recycle materials, and how to use them.” Mendel said contractors have been re-using concrete and asphalt for some time now, since it saves money. “But they are unaccustomed to recycling absolutely everything, and using that material in unconventional ways, and literally parsing it out.”

Designing inspiration

It’s those kinds of details that will be on display and talked about Friday night on Arch Street. As for the rest of the neighborhood there in North Philadelphia, Gajewsky said that interest has spiked in terms of planning opportunities that piggy-back off the Kroc Center. The sustainability czar said that includes possibly creating a sort of “eco-zone,” finding means of expanding the infill theory and the re-use of industrial space.

“We think the project will have a lot of influence in this neighborhood,” Stein said. “There’s a very narrow swatch of industrial land that comes ups and divides [Nicetown and Germantown]. We hope that our space will inspire others.”

There is no shortage of opportunities, just within eyeshot of the project’s construction gates. Directly across Wissahickon Avenue is the long-dormant Conkling Armstrong Terra Cotta Co., boarded up and rotting. Across the Amtrak railroad tracks to the south is a block-long empty industrial building that fronts onto Hunting Park Avenue, one of dozens like it within blocks of the new community center.

Politically, the center will be a nice feather in the cap of Mayor Michael Nutter’s administration. The Salvation Army credits Nutter as being among the first civic leaders to embrace the Kroc Center vision when he was a city councilman for the 4th District. And Alan Greenberger, Philadelphia’s city planning chief and acting deputy mayor for commerce and economic development, was one of the lead architects for the project. Greenberger was a partner with MGA for many years before leaving to head up the Planning Commission in late 2008.

The project is right in the sweet spot for a growing campaign to address formerly industrial lands by the city’s Redevelopment Authority and the quasi-public Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp. (PIDC is a also a partner on the Infill Philadelphia exhibit.) Nationally, a typical big city’s vacant or abandoned land totals about 15 percent, according to the National Vacant Properties Campaign, quoted in a recent article in Governing magazine.

Philadelphia’s Kroc Center is said to be one of seven scheduled to open in the United States this year, bringing the total to a dozen or more. Other cities include Camden; Dayton, Ohio; Grand Rapids, Mich.; Green Bay, Wisc.; Kerrville, Texas; Quincy, Ill.; and South Bend, Ind. In 2011, other big cities are due to open Kroc Centers, including Boston, Chicago, Memphis, Phoenix and Honolulu. In all, 31 sites have been proposed.

Additional funding for the Philly Kroc Center came from The Pew Charitable Trusts, Sunoco and a handful of major local donors. Money also came from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program ($4.95 million) and from the city of Philadelphia’s Cultural Corridor Fund ($2 million). The Salvation Army says that raised $25.7 million in contributions, close to its goal of $30 million.

The Kroc Center is “something that engages the community and adds benefit, especially on a piece of property that has not been adding community benefit for quite some time,” Gajewski said.

Contact the reporter at thomaswalsh1@gmail.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.