The Goals of Zoning Reform, Part IV: Making procedures fair and consistent

In the next few weeks, both City Council and the Zoning Code Commission will reconvene. Council will begin holding public hearings on the commission’s proposals, and the ZCC will continue to fine-tune the draft code in preparation for submitting a final report. While it is ultimately up to Council to decide when to close public hearings and take action on the draft code, the ZCC and other stakeholder groups hope that the draft will be approved by the end of 2011.

In an effort to engage readers in the zoning reform process, PlanPhilly will post a series of stories over the next month that aims to measure how well the draft serves its stated purposes, which are laid out in the very front of the ZCC’s preliminary report. The reformed zoning code claims to promote four categories of purposes: sound planning principles, sustainable and environmentally responsible practices, growth and economic development, and fair and consistent procedures for the use of the code itself.

Each of these purposes carries a handful of sub-purposes, and in this series, PlanPhilly holds the draft code up to these purposes in order to evaluate its adherence to its goals. In the process, we hope to explain in general terms what zoning reform could mean to Philadelphians. If you haven’t been paying close attention to the four-year zoning reform process in our city, now is an excellent time to start.

Today, PlanPhilly looks at the fourth purpose for zoning reform, promoting “fair and consistent procedures for its use.” This is a big one, since “unfair” and “inconsistent” seem to be two terms that are widely associated with the current zoning process. And the draft claims to promote fairness and consistency in three ways: establishing a “single city-wide process” for applicants seeking exceptions or variances to receive input from the communities surrounding their proposed projects, making the zoning code readable and accessible, and developing supporting regulations with the agencies charged with implementing different provisions of the code.

Peter Kelsen, a ZCC commissioner and land-use attorney, said that the problem with the current system is that there isn’t a coherent system. “What happens is basically that, in different parts of the city, you can have different reviews and different timelines, which can lead to very different outcomes,” Kelsen said. So, for example, two similar building applications, one in Northern Liberties and the other in Point Breeze, may go through different review processes and potentially have opposite fates. While that may be appropriate, since Northern Liberties and Point Breeze are not the same neighborhood, what the draft does is codify the steps that an application must go through before being approved.

Many of the provisions that deal with fair and consistent procedures are laid out in §14-300, Administration and Procedures, which begins with a statement of purpose: “This section summarizes the roles and responsibilities of appointed and elected government officials and bodies primarily involved in the administration of this Zoning Code …” The chapter continues with descriptions of the specific authorities granted to City Council, the Planning Commission, the ZBA, L&I, the Board of License and Inspection Review, the Historical and Art commissions, the Streets Dept., and the Water Dept.

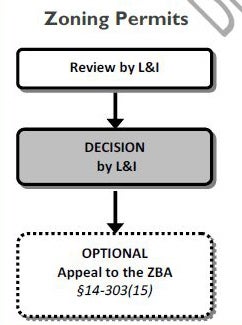

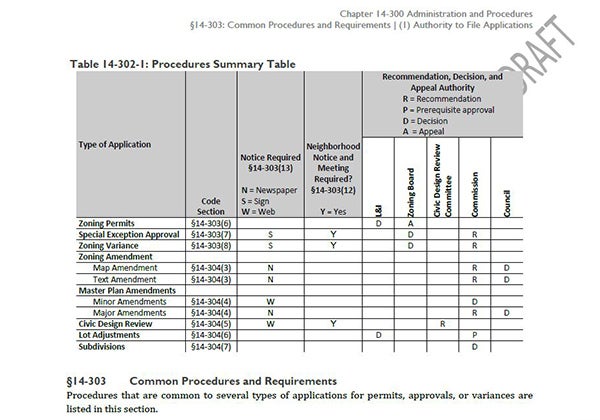

Most authority for “final action” in the draft falls to the Planning Commission and the ZBA, though Council’s authority is arguably the most important, since it is ultimately in charge of amending the text of the code itself. The Zoning Board maintains final action authority regarding appeals, special exceptions, and variances.

The draft provides a useful “Procedures Summary Table,” which neatly lays out which bodies are responsible for which decisions in different types of application processes. The code then describes which parties may file which types of applications. For example, anyone may file a request for an amendment to the code itself, but applications regarding “real property” must be filed by the property owner or an authorized agent.

Kelsen said another problem with the current system is that folks who are looking to get a better understanding of what the code means have nowhere to turn. “There’s no formal process to ask L&I for an interpretation and some guidance,” Kelsen said. But that’s changed in the draft as well. A new provision allows for members of the public to get “a written interpretation of the meaning of any provision of this Zoning Code,” so long as the interpretation doesn’t relate to an application before L&I, the ZBA, or the PCPC at the time.

Another provision in the draft, known as the “One Year Rule,” is a carryover of current policy. The rule prevents an applicant from submitting an application that is “substantially similar” to one that was denied during the preceding year. Kelsen said this bars applicants from “gaming the system” by repeatedly applying for the same project. But it also helps avoid one applicant from getting approved for a project similar to one that was recently denied to a different applicant.

Some of the most important and substantial changes to procedures, however, deal with special exceptions and variances. The current system is generally felt to be obscure, overly bureaucratic and, in the end, uncertain. Many people feel that the ZBA, which has the final say on special exceptions and variances, is unpredictable in its decision-making process.

“Frankly,” said Joe Schiavo, of Old City Civic Association, “they seem capricious.”

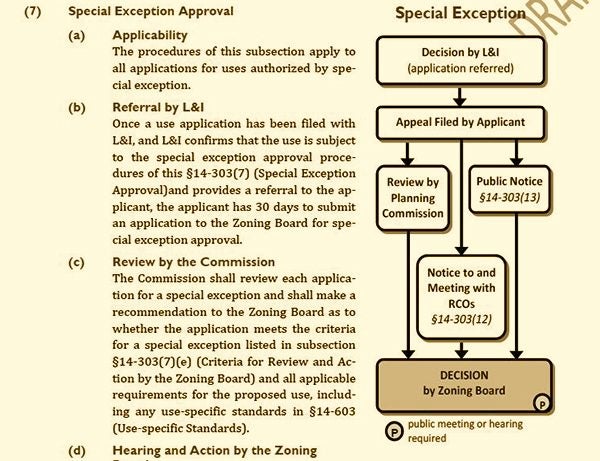

The draft aims to take the uncertainty of the process. For example, when an applicant wants to get a special exception for a certain use, there is now just one way to do it. After L&I makes an initial judgment that a use is subject to special exception procedures, the applicant must submit a special exception application to the ZBA within 30 days. The applicant must also notify Registered Community Organizations in the neighborhood surrounding the proposal, and hold a meeting with them within 45 days from when the application was filed to the ZBA. The applicant is also bound to notify the public of the proposal, and the application is reviewed by the planning commission. The Zoning Board holds a public meeting and makes the ultimate decision to approve or deny the application. And though RCOs’ input is merely advisory in this process, most community organizations seem to be supportive of the provision.

“I think it’ll be a net benefit,” said Schiavo. “For one thing, it forces communities to become better educated relative to the process.”

The process of applying for a variance more or less mirrors the special exception process, though the criteria for approval are different. For example, when dealing with use variances, “The Zoning Board may only grant a variance to allow any use not authorized on the lot by this Zoning Code if it determines that the denial of the variance would result in an unnecessary hardship.”

While Schiavo supports the passage of the code, he said he’s concerned about the lack of control over the amount or concentration of special exceptions and variances. In the same way that regulated uses may not be within a certain distance from each other, Schiavo says, the number of special exceptions and variances in a given area should be limited.

“I think [the draft] needs to be a little bit finer-grained,” Schiavo said. He added that he sees the new code as being “generally liberalized in favor of development.”

David Perlman, president of the Building Industry Association of Philadelphia, disagreed with that claim. “I would say that I think it defines development opportunities,” Perlman said.

“If you have a parcel,” he said, “and you know what you can put on that parcel, there’s no guessing game.” He described Philadelphia’s current zoning process, in which community organizations have greater negotiating power with developers, as a “pay-to-play” system.

Perlman believes the purpose of the reform is to take pressure off the ZBA by redefining what kind of development is appropriate in different districts, and clarifying the process for getting exceptions, when they’re necessary.

“It’ll define some of the gray areas that we’ve had for years,” Perlman said. Perlman was quick to point out that developers made concessions during the reform process. He said the BIA had a “laundry list of stuff” it wanted taken out of the code, which made it into the draft. But he declined to name any specific items.

His group, like Schiavo’s, wants to see the draft enacted.

Next Up: PlanPhilly looks at what the draft does to enhance the public realm.

Contact the reporter at jaredbrey@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.