‘Demolition by neglect’: How a taxpayer-funded quest to restore Wilmington’s Gibraltar mansion has failed for a quarter-century

A host of ambitious proposals have gone nowhere while Gibraltar deteriorated into a YouTube “haunted house.” Now the city has bought it. The mayor lives next door.

This investigative report was supported by a statehouse coverage grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Two men wield video cameras as they trudge through thorn bushes and high weeds on the hilly, rocky terrain to Gibraltar.

They’re not on the slopes of the mammoth, majestic limestone slab at Europe’s southern tip, however.

These guys are exploring the last walled estate in Wilmington, Delaware, stepping through an open doorway and over crackling glass and splintering wood into an empty room with peeling lead paint and disintegrating plaster.

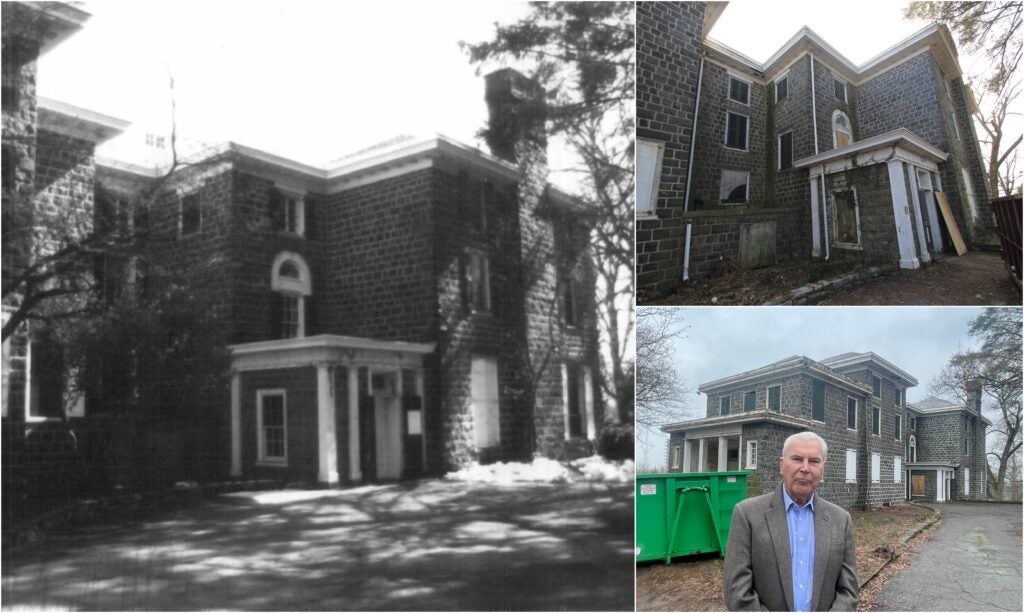

This Gibraltar, a towering, 12-bedroom,12,000-square-foot stone mansion built in 1844, is abandoned.

It’s been vacant, steadily deteriorating, for more than three decades.

The once-grand palace where some members of the du Pont family chemical dynasty entertained like royalty late into the 20th century is now home to vermin that scamper about decaying, long-neglected rooms.

Curiosity seekers, vandals, and an occasional squatter are the only other visitors to the mansion and 3,800-square-foot carriage house.

Some staircases are too dangerous to climb. Ceilings have fallen to floors, destroyed by rain that has poured for years through holes in the series of slate roofs. Fetid water fills tubs and toilets. Some insulation contains asbestos. Walls are spray-painted with graffiti.

“Whoa! Wow! This looks like a haunted mansion,” one explorer exclaims as he moves deliberately, with not a little trepidation, through the dank, darkened house.

That video, which the men shot a year ago, can be found on YouTube, as can several other clips of Gibraltar, including a 2020 music video produced by film director M. Night Shyamalan and performed by his daughter Saleka.

All document the decrepit state and long-lost grandeur of a historic 30-room mansion that has been a failed preservation project for more than a quarter-century — one that has already cost state and city taxpayers some $2.5 million, with more public funding on the horizon.

What started in 1997 with $800,000 in state funding with a well-intentioned goal of restoring the storied mansion to its former glory has instead stagnated as the home degraded into a high-profile eyesore in the Highlands, Wilmington’s wealthiest neighborhood.

To understand how this occurred and the possible path forward, WHYY News combed through hundreds of pages of documents in state, city, and court files, and interviewed several key players involved in trying to salvage Gibraltar.

The record reveals an exasperating, divisive saga defined by lofty aspirations by fledgling preservationists who pursued projects with several developers that collapsed. The parties later sought unsuccessfully to lift the legal restrictions on Gibraltar, and then the mansion descended into ruin, largely because nobody spent the several hundred thousand dollars needed to replace the porous roof system.

The restoration effort was initially put in the hands of the nonprofit Preservation Delaware, which was formed in 1993 with a mission to protect the state’s architectural and historical heritage.

Preservation Delaware quickly raised $2.1 million to restore and maintain the overgrown, unkempt gardens created in 1916 by Marian Coffin, one of America’s first female landscape architects.

But the group, which had never tackled a restoration remotely on the scale of Gibraltar, could never put together a viable project for the mansion and carriage house.

So in 2010, Preservation Delaware kept the 1.5-acre gardens and gave the other 4.5 acres to local developers David Carpenter and Drake Cattermole — the same duo whose earlier proposal for an office park at Gibraltar had been scrapped after it ran afoul of a conservation easement the state bought to protect the property “in perpetuity.”

A host of other so-called “adaptive reuses” for the mansion and carriage house — a bed and breakfast with restaurant, a luxury inn and day spa, a banking office, a boutique hotel with a wedding and event venue plus new housing — have also gone by the wayside.

The projects were derailed by either a lack of financing, inability to negotiate a lease or because they violated the easement that limits new construction at a property that since 1998 has been on the National Register of Historic Places.

Many proposals were also met with vehement opposition and ardent support from residents of the Highlands, whose wide, tree-lined blocks include dozens of other imposing stone or brick homes.

Yet even as government officials received a litany of complaints about Gibraltar’s condition — about trespassers, partiers, graffiti artists, and even a pornography crew filming a scene inside — the state never exercised its right to go to court to force the owners to repair the escalating damage. The city only cited the owners for high grass when it could have hit them with dozens of code violations.

The lack of strong, persistent government intervention rankles residents in a neighborhood where city inspectors issue citations for failing to pick up dog droppings.

“For 25 years, there’s obviously been a lot of missteps, but for the last 13 years, the mansion and grounds have been in a state of just utter neglect,” said Maggie Mesinger, who lives near Gibraltar. “The failure to enforce city and state codes and easement requirements has contributed to the problem.”

Wilmington to the rescue, or bailout for developers?

Now, after decades of inaction except for periodically letting city police use Gibraltar to train or exercise its K9 dogs, the Wilmington government has injected itself into the restoration effort.

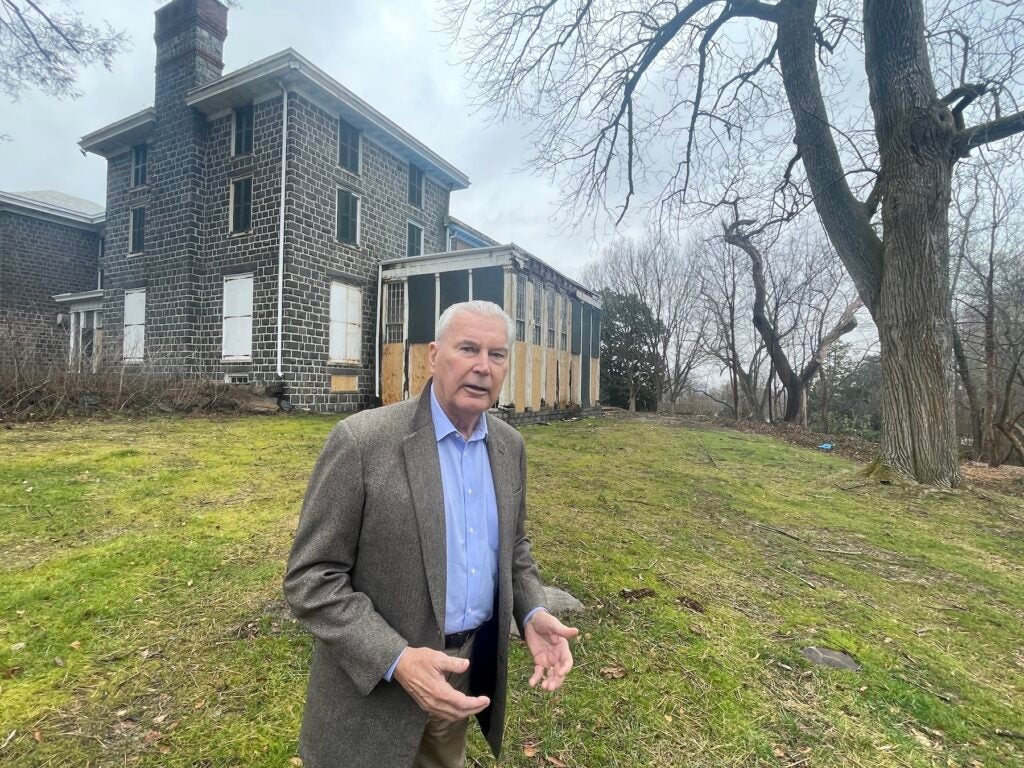

Last year, Mayor Mike Purzycki — whose own sprawling home borders the mansion — began using city taxpayer money to board up windows and make other outdoor improvements. To showcase the efforts to date, his office released a PowerPoint presentation with before and after photos last month.

In December, the city paid Cattermole and Carpenter $900,000 it received from the state to buy the property and agreed to assist developers with plans to have up to three homes built on adjoining land.

Cattermole and Carpenter, who owned the property with their limited liability company Gibraltar Preservation Group, would not agree to be interviewed about Gibraltar. Their attorney, William Rhodunda Jr., said in a written statement his clients “invested well over $3 million trying to implement a vision for the property” but could not overcome formidable obstacles.

“Unfortunately, much misinformation has been spread about this project by its opponents, which was disappointing and frustrating as this property could have been fully restored in a short period of time,” Rhodunda wrote. “The exorbitant delays, community controversy, and the poor economy resulted in the inability to secure a tenant or purchaser to make the project financially feasible.”

Purzycki, who is not seeking a third term and leaves office in January 2025, told WHYY News Cattermole and Carpenter were poor stewards of Gibraltar, and the mansion has a better chance at salvation in the hands of a public agency — not developers looking to profit.

“Either we commit to preserving it, or it will inexorably rot beyond salvation,” the mayor said.

Purzycki says the immediate plan is to replace the roof and make other exterior repairs before the city seeks a long-term solution.

‘It’s just been painful to watch this thing deteriorate the way it has and I finally got tired of watching the results of so much infighting over this place,” the mayor said. “And I just committed myself to doing what I thought was the very, very best thing to do and that is just to get the city to buy it. It is truly a treasure. If it’s maintained the way it should be, I think we can really rescue it.”

Purzycki said it would have been pointless to issue dozens, if not hundreds of citations against Gibraltar’s owners. “You’re not going to negotiate a path forward if you walk in and start throwing fines around to everybody,” the mayor said.

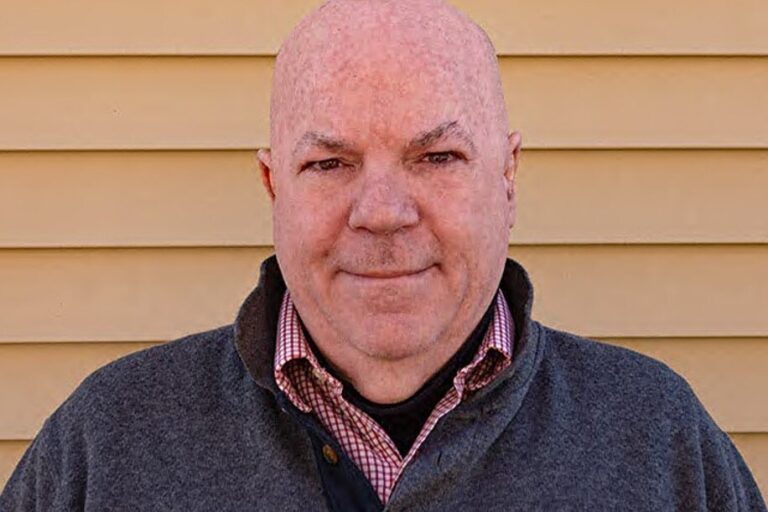

But Michael Melloy, who grew up in the Highlands and has spent the last few years prodding state and city officials to force the developers to fix up Gibraltar, said Purzycki should have held Cattermole and Carpenter accountable instead of using taxpayer money to “give these negligent people a sweetheart bailout deal.”

Melloy says the decades-old fiasco has been a classic case of “demolition by neglect” — allowing a building to suffer severe deterioration, potentially beyond the point of repair.

Melloy used a nautical analogy to describe the restoration quest that after all these years still has no fixed course.

“This is kind of a ship that didn’t have a captain and it left shore,” Melloy said. “It had problems and got sort of repaired. And then it was set on its way without really any clear navigational management.”

Nor is the shoreline in sight.

State pays $800,000 for development rights

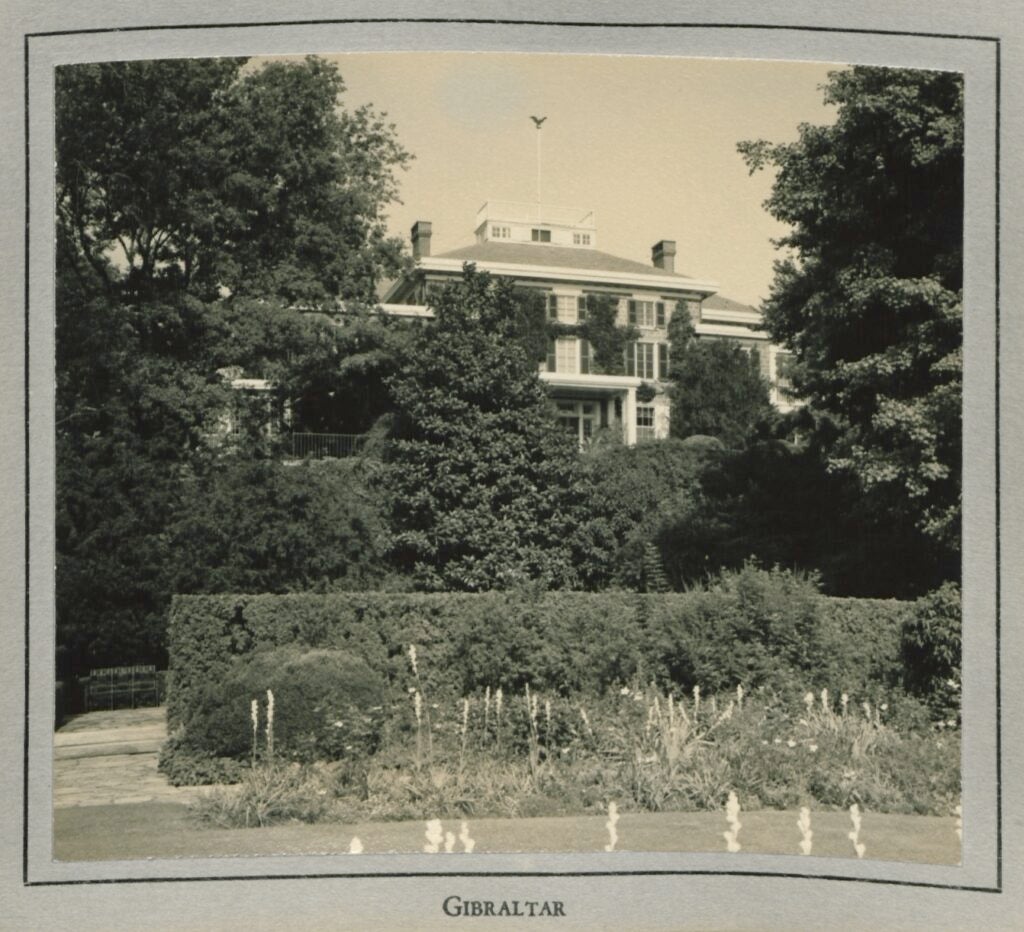

The quest to restore Gibraltar began in the early 1990s, when a family trust overseen by Hugh Rodney Sharp III grappled with the fate of the estate at Pennsylvania and Greenhill avenues, along the picturesque western gateway to Wilmington just past the private Tower Hill School.

The home was built of blue stone from nearby Brandywine Creek, where the DuPont Co. launched its empire with gunpowder mills in the early 1800s. Among Gibraltar’s stunning features were its library, conservatory, carriage house, pool, and gardens.

Sharp III’s grandfather, Hugh Rodney Sharp Sr., was a DuPont Co. executive whose wife Isabella was the company founder’s great-great-granddaughter.

In 1908, the couple bought Gibraltar, expanded the home, and hired Coffin to create gardens. Coffin also designed much of the open spaces at the University of Delaware and the nearby Winterthur museum, another restored du Pont family estate.

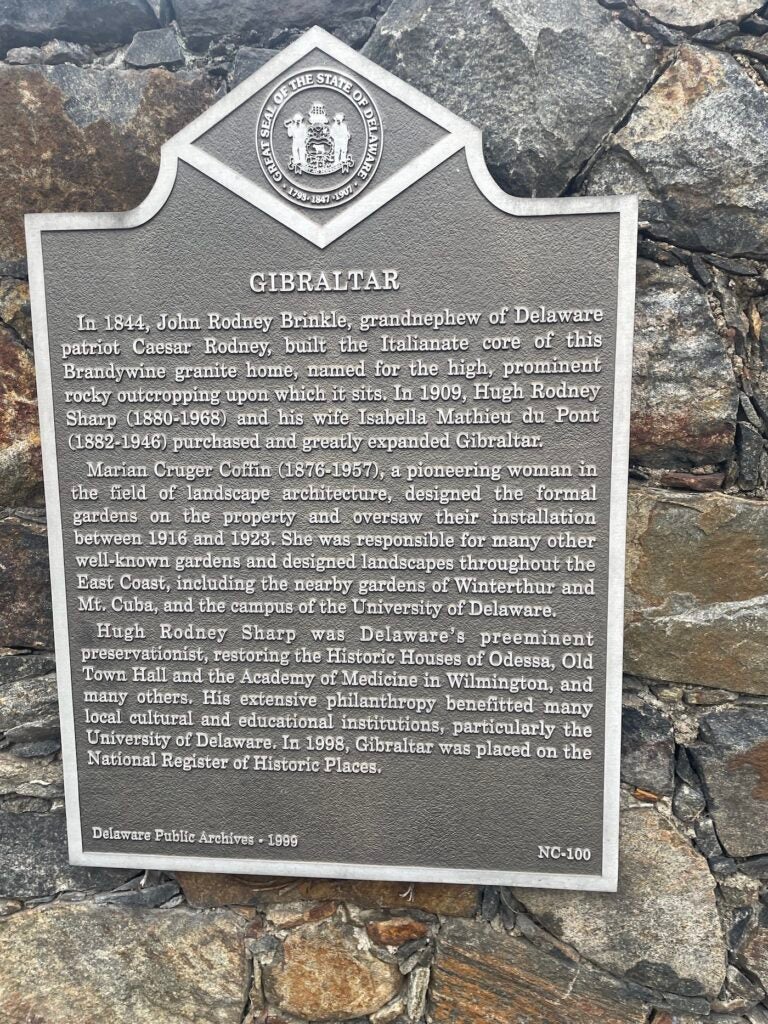

Sharp Sr. later became Delaware’s “preeminent preservationist,” with projects in Wilmington, Odessa, and elsewhere, according to the state’s bronze plaque on Gibraltar’s wall. Sharp was also a philanthropist who gave generously to his alma mater, the University of Delaware, where a laboratory, residence hall and several scholarships bear the Sharp name.

Sharp Sr. died in 1968 and left Gibraltar to his son, Hugh Rodney Sharp Jr., who passed away in 1990.

After Sharp Jr.’s death, the family sought to sell the estate, which was already in serious need of renovation. Sharp III, who also was president of the philanthropic Longwood Foundation, lined up a developer to demolish the mansion and build upscale housing.

However, neighbors objected to the proposal that required a zoning change, so city officials mounted an effort to preserve Gibraltar and get it on the historic register.

Those efforts drew the attention of Nathan Hayward III, a du Pont family descendant who in the 1980s had been in the cabinet of his cousin, Gov. Pete du Pont.

Hayward, also a distant cousin of the Sharps, has fond memories of Gibraltar from growing up about a block away.

“When we were kids we had permission to go over and play there on the rocks, and not destroy anything of any value,” Hayward recalled. “The trees I remember as being just glorious. The family kept the property in immaculate condition. We felt very privileged to play there.”

But like anybody else paying attention in the 1990s, Hayward knew his childhood playground had deteriorated.

Hayward was on the Delaware Open Space Council, which advises the state about potential purchases to expand parks, forests, fish and wildlife areas, and cultural sites.

“So I said, well maybe the state should take a role here in trying to preserve this beautiful estate and figure out a useful repurposing of the house and the grounds,” Hayward said.

That led to the state allocating $800,000 in 1997 in return for a conservation easement that dictated what could and could not be done at Gibraltar.

The state paid that money to the Sharp trust, which gave the property to Preservation Delaware.

State lawmakers also gave the group $100,000 from the so-called Bond Bill — which allocates tens of millions of dollars for construction projects such as roads and schools — to help with the costs of acquiring Gibraltar.

Easement’s limits on Gibraltar ‘shall apply forever’

Preservation Delaware inherited a weighty responsibility.

The conservation easement obligated the owners and the state Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs to protect Gibraltar from “any disruption and/or other occurrences which might interfere with the beauty and unique character … for the benefit of this generation and generations to come.”

The 10–page document also made clear that restrictions on the property “shall apply forever.”

To that end, the easement declared that the mansion’s “architecturally significant characteristics of Italianate and Colonial Revival periods … exhibit a high degree of site and structural integrity” that must be protected.

It specified the main entry hall with staircase and foyer, dining room, living room, library, and glass-walled conservatory, window sashes, wooden trim, terracing, statue, iron gates, and railings had to be retained, repaired, or replaced to the extent possible.

Commercial and residential uses were permitted, but any new construction could not exceed 4,000 square feet — the size of a McMansion — and had to be approved by the state and comply with federal “standards for the treatment of historic properties.”

The state could enter and inspect Gibraltar, “require the restoration” of any “damaged” areas, and “demand corrective action” within 30 days. If repairs were not made, the state could go to court to force the owner to restore Gibraltar “to its prior condition.”

Dee Durham, a current member of New Castle County Council, headed Preservation Delaware at the time. She said the four-year-old group had several members who lived in the Highlands and welcomed the opportunity despite Gibraltar’s condition.

“The property had already been empty for quite a while and had some leaky roofs and that sort of thing,” Durham told WHYY News recently. “It was certainly not being maintained to the utmost standard even at that time when we acquired it.”

2 plans to turn Gibraltar into elegant inn collapse

Preservation Delaware moved to restore the estate on two separate fronts.

Members first raised money to spruce up the gardens and create an endowment fund for their maintenance. The revamped gardens opened to the public in 1999, and remain in operation. High school kids in prom outfits flock there for pictures, as do wedding parties.

The group sought proposals to restore the mansion and in 1998 struck a deal with Someplaces Different, a New Hampshire company with several historic hotels.

Gibraltar would become a bed and breakfast with 31 rooms — 14 in a new building — and meeting/conference space. The greenhouse and garages would be a 60-seat restaurant, and the pool house would be a lounge. A visitor’s center would highlight Gibraltar’s rich history. The developer would take advantage of tax credits for investing in a historic property.

Neighbors welcomed the plan, and the city Zoning Board of Adjustment approved the new use for the residential property. The state also amended the easement to allow an additional 2,500 square feet of construction, raising the total permitted to 6,500.

Preservation Delaware’s newsletter touted the coming “elegant country inn” and predicted a summer 2001 “grand opening.”

The optimism was premature.

High hopes collided with steep costs and by May 2001, the deal was off. Preservation Delaware’s newsletter said Someplaces Different was “unable to arrange an acceptable financing package.”

So Preservation Delaware pivoted to a proposal by Tom Lantry, a respected restorer of historic properties. His projects included turning Philadelphia’s Thomas Bond House into a 12-room bed and breakfast in Old City that’s still in operation today.

Lantry planned a luxury inn with 15 rooms, all with private baths, and a European-style day spa with services such as massages, aromatherapy, and skin wraps.

Once again, enthusiasm abounded. Yet the parties could not negotiate a lease, and in 2004, Preservation Delaware informed residents the partnership was “officially severed.”

Board president Rebecca Tulloch wrote that Lantry wanted her group to pay for “improvements made to the property should the venture not succeed by a certain date. This risk could not and cannot be taken on by our nonprofit organization.”

‘Honestly, we were not protecting that site’

By then, Trent Margrif had become Preservation Delaware’s executive director, leaving a similar post in Oklahoma.

Margrif, now a professor at Appalachian State (N.C) University, recently told WHYY News he felt saddled with the run-down mansion and carriage house, where his one-person office was located.

“I personally didn’t care about the mansion succeeding,” Margrif said. “In my mind, if the gardens could be a public presence, that was far more important. It was irritating to me that we were attached to this property to begin with.”

Margrif called it “an afterthought” to spend from the statewide group’s annual budget of roughly $200,000 on minor mansion repairs when it needed a monumental overhaul.

The group did spend $30,000 in 2005 on a temporary roof over the greenhouse, and replaced two flat roofs over the mansion that had collapsed, Margrif wrote to neighbors, but stressed that the building “is rapidly growing worse.”

Among the “many immediate needs” he described was “water leaking through the 1910s slate roof,” and he estimated a new roofing system could cost up to $500,000.

The group also received another $60,000 more from the Bond Bill in 2006. Then-board president Tulloch later wrote that most went toward roof and gutter repairs requested by the state to prevent “further water infiltration and damage.”

Margrif said he walked through the mansion once a week and was appalled by the steady decay: broken windows, peeling paint, mold, asbestos, failing floors, broken shutters, animal droppings, and encroaching vegetation. He grew tired of seeing graffiti and other remnants of teenage invaders.

Once, he encountered a few naked men and women and people with video cameras. He’d stumbled onto an amateur porn set.

“I said, ‘Look guys, the joke’s on you. There’s so many dead raccoons and pigeons in here, I don’t care how much you’re gonna shower, this stuff isn’t going away.’” Margrif recalled.

The actors threw on their clothes, and the crew bolted Gibraltar.

“Honestly,” Margrif said, “we were not protecting that site.”

Office park with major new construction selected

Preservation Delaware again sought proposals for the mansion, with a new stipulation: there would be no leasing costs.

Dozens of interested parties toured Gibraltar, and nine submitted proposals. A hospital wanted to treat wounded Iraq and Afghanistan veterans there. Educators wanted to open a Spanish language school. Developers submitted plans for townhouses, restaurants, and retail shops.

In November 2005, the board chose a plan by Cattermole and Carpenter, operating as CCS Investors, LLC, to expand Gibraltar into an office park.

Carpenter is a du Pont family descendant whose late father, Ruly Carpenter, once owned the Philadelphia Phillies. Cattermole was then married to Carpenter’s sister. The two men have developed numerous properties in northern Delaware.

Their plan called for three tenants, with one each in the mansion, carriage house, and a new 12,000-square-foot building. The new building was later reduced to 10,000 square feet, but still exceeded the easement’s 6,500-square-foot limit by more than 50%.

There would be 97 parking spaces, with 23 of them under the new building.

Tulloch later wrote that the board realized the easement would need to be amended again, but stressed that the developers’ plan was “the most exemplary.”

Attempt to amend easement triggers battle royale

The office park plan kicked off a three-year battle that divided neighbors, led to a protracted legal fight, and pitted the developers and Preservation Delaware against the state.

Some neighbors objected to a zoning variance for commercial office space and a new 10,000-square-foot building. The city zoning board granted it by a 2-1 vote, triggering a lawsuit and appeals from residents. The Delaware Supreme Court ultimately upheld the decision.

That was only the first of two steps, however. The more problematic request was for a second and larger change to the easement.

Timothy Slavin, who had headed the state historical affairs division since 2005, met with residents and sought written comments. He received about 150 responses, representing all sides.

Highlands resident Pamela Price expressed her “strong opposition” to a project that “could easily result in destabilizing this lovely part” of Delaware’s largest city. “The property has been abandoned for 15 years, so it will not hurt to take some more time to find a better alternative,” Price wrote.

Austin Edison wrote that permitting excess construction would mean taxpayer money had been “misspent.” Should the easement be changed, Edison suggested the developers pay “$2 million or so” in compensation.

Heather Richards Evans said a decision to “eviscerate” the easement would set a “dangerous precedent” and discourage others from preserving land. “A community that fails to protect some of the features that link those who live here now with those who came before us eventually loses itself,” she wrote.

Hayward, who was still on the Open Space Council, wrote that the request “flies in the face of well-documented and thoroughly discussed options to save both the physical property and to protect the character of the neighborhood.”

Should the state consent to the change, Hayward said Preservation Delaware “would be obliged to repay the state’s investment, which I know it is neither able, nor desirous to do.”

Supporters included the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Delaware Economic Development Office, then-Mayor Jim Baker’s administration, and dozens of residents.

One was Hugh Rodney Sharp III, who oversaw the family trust that the state paid for the easement.

“Since the gift to Preservation Delaware, the structures have suffered severe deterioration,” Sharp III wrote. Allowing more construction was “perhaps the last hope that the historic structures can be saved. … the alternative will surely be Delaware’s loss of this landmark.”

Lee Kallos agreed, writing, “As I look at Gibraltar crumble and become more of an eyesore. I hope that the neighbors realize that this plan is the only hope to save it. I encourage you to approve the use and get things under way SOON.”

Scott Porter praised the plan as “non-intrusive” and in keeping with “the spirit of preservation.”

Donald Mell supported the plan but excoriated Preservation Delaware as “the main culprit here.”

Mell wrote that “over a million dollars of taxpayer funding was squandered by PDI over the past decade as they dilly-dallied around with one unrealistic project after another. With that said, we cannot, as some would like, just sit around and wait for the mansion to fall down.”

Preservation Delaware’s Tulloch acknowledged she had “misjudged the sensitivity of the neighbors” but argued that the office park was “good for Gibraltar and the neighborhood. … Our intent is to be a good neighbor and a steward of the property entrusted to us.”

Wendie Stabler, the developers’ lawyer, wrote that her clients would spend $10 million to restore Gibraltar and pay $30,000 more annually to care for the gardens.

Stabler had harsh words for foes, writing that they “know full well that to deny the amendment request means certain loss of the mansion. They frankly do not care.”

‘We were there to protect the state’s interest’

Slavin rejected any change to the conversation easement.

“Our interest in the property is as strong today as it was in 1997 when we made our investment in the property on behalf of the citizens of Delaware,” his letter to Margrif said. “The proposed amendment would significantly alter the easement.”

Slavin cited state law that says “property acquired or improved” with Open Space money “shall remain in public outdoor recreation and conservation use in perpetuity.”

Slavin’s letter added that the state Legislature could remove the easement, but the state would be entitled to a share of any sale or rental income.

Slavin, who retired in 2022, told WHYY News in a recent interview that Preservation Delaware was wrong to keep pushing for a second easement amendment.

“It was a condition that Preservation Delaware invited onto the property” in 1997, Slavin said. “The state had invested money to ensure that those values were maintained. We were there to defend the state’s interest in that property.”

Margrif countered that the state and residents should have been more flexible with a viable project that would have prevented today’s sorry state of Gibraltar.

“Historic preservation is a lot more about compromise than anything else,” he said. “And on that side, we never got it.”

Margrif told WHYY News he applauds Cattermole and Carpenter for being willing to spend millions of dollars to restore Gibraltar.

“Drake and David knew what they were doing,” Margrif said. “They put up the best sort of presentation here. They had more experience. But I don’t think they figured out how difficult this was going to be.”

Preservation Delaware gives mansion to developers

Their plans thwarted once again, Preservation Delaware struggled to find a solution.

Their challenge was compounded in August 2008 after a state inspection, and Slavin urged a slew of “corrective measures” to “stem the downward cycle of deterioration.”

Among the steps he “strongly” recommended:

- Begin long-term stabilization by following federal standards for “mothballing historic buildings” and start by boarding up windows and providing ventilation.

- Remove trash, feces, and carpeting, hire a “cleaning firm to make it broom clean,” and maintain that condition.

- Remove shutters and store them inside.

- Repair a leak in the pool house roof.

- Clear vegetation from the mansion’s perimeter.

- Inspect the mansion daily.

Slavin stopped short of ordering the fixes, though, and stressed to WHYY News that such a decree would take costly legal action his office was not prepared to initiate.

“A conservation easement, especially on a cultural property, is the result of two cooperating parties that accept the conditions,” Slavin said. “So we always did our best to monitor as best we could, to ensure as best we could, that things were moving along.”

Yet Preservation Delaware had already taken a major step to rid itself of the mansion, dividing the Gibraltar property into parcels: the gardens it maintained, and the mansion whose care it could not afford.

Cattermole and Carpenter kept looking for a workable plan, too, and in 2009 presented a proposal to Slavin’s office — but not the public — that called for less than 6,500 square feet of new construction. Slavin pronounced it within the bounds of the easement.

And in January 2010 — while the developers pursued potential tenants — Preservation Delaware gave the 4.5-acre mansion property to Cattermole and Carpenter, who had formed Gibraltar Preservation Group, LLC.

But like so many other propositions for Gibraltar, nothing came of that one either.

That left Gibraltar in the hands of the developers whose plans had not gone forward but now were obligated to not only abide by the easement’s terms, but to pay property taxes and maintenance costs.

Preservation Delaware also moved on from the mansion, transferring its office to the New Castle Court House, another historic property about 10 miles away.

Slavin said recently that “from the outset,” the choice of Preservation Delaware to oversee Gibraltar’s restoration was misguided. “In hindsight, it certainly does look like that,” he said.

Slavin said Gibraltar should have been entrusted “to a party that had the funding lined up and was going to go ahead and do the work immediately. I don’t know that it ever was really on sound footing.”

Durham, who returned to Preservation Delaware as board president in 2022, said the failure wasn’t from a lack of trying or incompetence.

“It’s not an easy project,” Durham said. “It’s a very expensive project, and financial markets have been up and down in the intervening years. It’s complicated.”

A decade later, plan surfaces for hotel, houses

Once Cattermole and Carpenter became owners, more than a decade passed before any proposal was presented to the public, even as the decay intensified and amateur filmmakers descended on the abandoned mansion with video cameras.

In 2012, Cattermole spoke about his hopes with Delaware Public Media, saying he and Carpenter were having active discussions with financial advisory firms, law firms, and trust companies. “That’s probably the most likely end-user,” he said in that interview.

Though no restoration work was scheduled, Cattermole proclaimed Gibraltar in good hands.

“As long as we just do the regular maintenance, we’re fine,” he told DPM. “The gutters are always clean. Other than peeling paint, we don’t have any threats of further cracking.

“We’ve stayed on top of the roof breaches, so without the water breach, it’s in great shape. The exterior will definitely be preserved.”

Over the next several years, the owners patched roofs periodically but never put a new roof on, and water kept streaming inside, wreaking even more havoc. Sections of bright blue tarps that once patched roofs flapped in the breeze or were strewn about the expansive lawn.

Gibraltar’s owners had, however, bought two adjacent properties through their venture BDK Brinkle, LLC. In 2020, they began collaborating with 9th Street Development Company (9SDC) on a potential partnership with Gibraltar and the other two parcels, plus a vacated, overgrown section of a city-owned street.

Rob Snowberger, one of 9SDC’s principals, is a lifelong resident of the Highlands who has restored several historic buildings in downtown Wilmington. Snowberger told WHYY News he was intrigued by the prospect of returning Gibraltar to the splendor of its heyday.

“We came to the conclusion that it’s gonna be about $12 million to $15 million to fix that place up and make it into something,” he said.

So 9SDC proposed turning Gibraltar into a boutique hotel, wedding venue, and restaurant. To make it work financially, 9SDC proposed building nine large homes and nine townhouses on the other two properties.

That plan, presented to some Highlands residents at Gibraltar’s gardens in June 2021, would have violated the easement because some homes were envisioned on Gibraltar property, and not associated with the mansion or carriage house.

Faced with neighborhood opposition, 9SDC then proposed 15 smaller homes — none on Gibraltar land. The revised plan required city approval for rezoning, subdivision, and abandonment of the street, but fell within the bounds of the easement.

Slavin wanted more immediate fixes, too. In December 2021, he wrote to Cattermole, urging him to “mothball” the mansion and “remediate conditions which are potentially causing undue deterioration. … The current condition of Gibraltar suggests that this standard is not being respected.”

Snowberger objected, writing that forcing a “mothballing” of the mansion “would interrupt a long-pursued, naturally-progressing historic project application and will cause us undue hardship.”

Slavin relented, allowing Snowberger to board up windows with painted plywood, remove trash, do spot waterproofing, and re-tarp roofs. But Slavin also warned in writing that should renovation not begin in 2022, “we reserve the right to revisit this issue and take necessary actions.”

Slavin said he gave Snowberger leeway because 9SDC spent $40,000 applying for tax credits to offset project costs. “They were very serious and real about going forward,” Slavin said.

That remedial work was completed, but by the summer of 2022, Snowberger’s revised proposal had gone kaput.

Snowberger said the key reason was the sudden death of Ruly Carpenter in late 2021, ultimately leading to the loss of financing his son and Cattermole had expected.

“That’s what took the air out of our sails,” Snowberger said.

‘It’s raining like crazy and the roofs are still open’

Once again, it was back to square one, with a mansion Snowberger said was in a “more deplorable” state than ever.

Snowberger said there was plenty of blame for the mansion’s waterlogged and worsening condition.

“I don’t defend what Drake and David did for that amount of time and not putting a roof on the place, but at the same time, Preservation Delaware is equally as culpable,” Snowberger said. “No one who’s owned that place for 30 years has put a new roof on it.”

Melloy, the Highlands native who has spent years documenting what’s happened with Gibraltar, says Slavin should have taken a tougher stand, especially in 2022.

“The state should have said, ‘We’re going to resume what we were doing before because it’s clear that you’re not doing any restoration. In fact, it’s raining like crazy right now and the roofs are still open on the property,’” Melloy said.

Slavin retired around the same time Snowberger’s plan disintegrated, and top deputy Suzanne Savery became director.

Slavin told WHYY News that going to court wasn’t a practical solution or an expense the state was willing to make.

“It was an absolutely frustrating sequence of events there,” Slavin said. “I think we did everything we were capable of doing. It’s the result of a party that owned it, that knew those conditions, that simply did not live up to the expectations.”

Savery would not agree to an interview. A spokesman echoed Slavin’s sentiments in saying her office “does not have the legal authority or the enforcement mechanism to require that an owner make any improvements or modifications to Gibraltar.”

Mayor steps into fray with stabilization plan

By May 2022, Mayor Purzycki was fed up with the property next door, writing to neighbors that since moving there in 2006, he had witnessed the degradation of Gibraltar from his kitchen window.

Using his personal stationery, the mayor decried “the forlorn condition of the main house and grounds.”

Purzycki outlined Snowberger’s vision, and suggested the city buy the mansion and perhaps contract with 9SDC to restore it for an unspecified use that “allows Gibraltar to become the storied property it once was.”

Purzycki is no novice to urban revitalization.

Before being elected mayor, he spent two decades running the state-funded Riverfront Development Corp. In that role, he spearheaded the transformation of south Wilmington’s Christina River waterfront from a polluted wasteland into a thriving residential, dining, and entertainment destination — essentially a city within a city — all while Gibraltar floundered.

The mayor sprung into action. By June 2002, the city obtained $1 million in additional state Bond Bill money “for future revitalization” of Gibraltar.

Last spring, under a separate deal with Cattermole and Carpenter, the city began shoring up the property — spending about $250,000 to put plywood on broken windows, clear falling trees and debris, and more.

And in December, the nonprofit Wilmington Land Bank used $900,000 from the Bond Bill grant to buy Gibraltar. The purchase, which did not require City Council approval, was highly unusual for the Land Bank, which the city created in 2016 to return dilapidated, abandoned properties to productive use.

The Land Bank obtains lots and homes through donations or paying just a few thousand dollars. The group currently owns about 200 properties, almost all located in run-down parts of Wilmington.

Although Purzycki’s 2022 letter to neighbors had said Cattermole and Carpenter “will not benefit from this state grant,” that’s exactly who received almost all of the $1 million of the Bond Bill cash.

Purzycki said he doesn’t recall writing that sentence, but said the only way to get Gibraltar was to pay for it.

“There’s no way in the world these guys are going to just give up the property for nothing. That was never a choice,” he said. “They have every right in the world to sell it and from my perspective buying that property for roughly a million dollars is the biggest bargain that you could imagine.”

The deal Purzycki forged with Cattermole and Carpenter also sets the stage for up to three new homes on the properties bordering Gibraltar, with Purzycki obligating the city to pay an engineering firm to prepare a subdivision plan for one property.

In addition, Purzycki agreed to ask City Council to give the developers the unused street bed connecting the properties. Should Council refuse, the city must pay them another $350,000.

Melloy suggested the mayor has a conflict because he lives next door. He also accuses the mayor and city of being far too generous to owners who let the property fall to pieces.

“They’re off the hook for the significant damage they caused,” Melloy said. “Cattermole and Carpenter so far are the big winners. No question about it.”

‘A sad thing to look up and see haunted house’

Purzycki shrugged off the criticism, saying his administration has spent money on restoring homes and neighborhoods all over the city. Purzcyki also said the city plans to spend several hundred thousand dollars more from the mayor’s discretionary fund to further shore up Gibraltar.

“We ought to be able to put enough money behind this project so that we can see it clear to a point of stability,” Purzycki said. “The exterior is taken care of, we get a roof on the building, and it looks like a worthy complement to the gardens, which everybody loves. But it’s a sad thing to be in the gardens and look up and see the haunted house up above.”

Once that’s accomplished, Purzycki said options can be studied.

The mayor said a comprehensive restoration of Gibraltar is possible, but what’s more realistic is that sections of the mansion get renovated with financial help from philanthropic foundations, and the mansion gets opened periodically for public tours.

Mesinger, another neighbor closely monitoring developments, says residents deserve a true voice in Gibraltar’s course.

“There are neighbors who would prefer that their tax dollars aren’t being spent to clean up after the years of neglect, but would love to be included in an authentic conversation about where we could all go from here,” she said.

Purzycki says he welcomes ideas to take Gibraltar to a brighter future worthy of its stature and insists his moves will help right a ship that has been adrift for far too long.

“This is a 19th-century country house,” the mayor said. “It’s a remarkable architectural treasure to have in the city of Wilmington. How many buildings do we have in the city that were built before the Civil War? I think it’s going to be an asset that doesn’t have to explain itself to anybody.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.