Breathing new life into the site of Delaware’s only Revolutionary War battlefield

The site of Delaware’s only Revolutionary War battle is being reimagined to tell the property’s story in a way that acknowledges Black and Indigenous history.

Listen 5:00

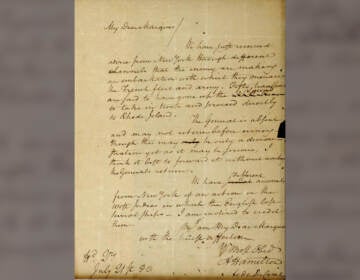

The Cooch home built near Newark in 1760 was used by British Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis after the only Revolutionary War battle on Delaware soil. (Mark Eichmann/WHYY)

Just a few hundred feet from the roar of I-95 near Newark, water gently falls over a dam made up of piled boulders. One of the boulders bears the name of the Cooch family and “1792,” the date the dam was built to divert the water to run a nearby mill.

The area around the mill and dam is best known as the location of a 1777 Revolutionary War battle. The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge was the only real fight of the war on Delaware’s soil.

A group of advocates is now working to expand the focus and tell a fuller story about the history of the property and the people who lived and worked on the land, long before and after the battle. That includes both the indigenous Lenape who once lived on the land as well as those enslaved by the Cooch family.

The Friends of Cooch’s Bridge formed as nonprofit about a year ago and is now raising money to do restoration work on the house, built in 1760, and other buildings still standing on the property.

“The intent is to try to get a level of awareness of what the site is,” said Wade Catts, archeological consultant for the Friends.

The group will also offer suggestions to the state Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs as they develop plans to eventually offer public tours of the site.

“There’s a lot of different people who were here. There’s a community that this place connects to. There’s the farm life, there’s the battle, there’s the prominent family that lived here,” said Vince Watchorn, president of the Friends group. “There are all sorts of people who lived here and every single one of them matter because they all have contributions.”

In 2018, the state Division of Historic and Cultural Affairs purchased the historic Cooch home built in 1760 to preserve the building and about 10 acres of the property surrounding the house.

The Friends group is currently working to raise the $1.7 million which HCA says it will cost to complete repairs to the buildings over the next ten years.

Intentionally inclusive

From the start, the group has been focused on making sure the stories told about Cooch’s Bridge are inclusive.

“We decided intentionally that if we’re going to do this, we’re going to do it inclusively. We’re going to do it in a way that recognizes the importance of the battle and also pulls in all these other people who lived and worked and died here over many, many eras, not just the Colonial era,” Watchorn said. “Telling that full story, and telling it truthfully, is something that we’re really committed to.”

Part of that more inclusive history includes the story of David James, a young man enslaved by the Cooch family in the late 1700s. Watchorn says the group is working to discover more about the lives of James and others enslaved at the property.

James’ descendants, some of whom live nearby, recently visited the house to learn more about the history of David and better connect their story to his.

“When the James family was here a couple of weeks ago, they brought their research which we had not seen, Wade had his research, which they had not seen, and it matched,” Watchorn said.

It’s believed people were enslaved at the property as early as 1754. Records of enslaved people being handed down through the family’s wills continue for more than a hundred years after that.

Details like that are an important part of the story of Delaware’s history for Marilyn Whittington, who serves on the board of Friends of Cooch’s Bridge.

“I didn’t learn Delaware history fully until I was about 55 years old,” said Whittington. “I learned my Delaware history in 4th grade… It was a narrow, very narrow lens.”

In her previous work as executive director of the Delaware Humanities Forum, Whittington said she was shocked to see state leaders debating how to present the story of another historical property in Delaware, Dover’s John Dickinson Plantation a few decades ago.

“They were arguing back and forth philosophically, ‘Can we really use the word plantation?’ ‘Are we really going to acknowledge that we had slaves, or can we call them indentured servants?’ And I’m there in the midst of this saying, ‘Why would you not tell the truth?’”

Whittington said having the James family come to the Cooch home is all about honoring their family history.

“It’s to acknowledge their existence,” she said. “Who doesn’t want to be recognized? Whatever your story might be, as a human, we must acknowledge one another.”

Watchorn wants inclusivity in more than just the storytelling.

“We’re trying to not just acknowledge but engage, to make folks who are connected to all those different histories a part of our thought process about how we experience the property, how we make our own plans as a community group, how we establish ourselves as an organization and how we see the future,” he said. “We want all of those voices in. So, it’s not one group working on behalf of others, but everyone representing being a part of it together.”

Bigger than the battle

The battle has long received top billing in state history books. For the unfamiliar, the battle was part of the Colonials’ effort to delay the British advance on Philadelphia using the Christina River at Cooch’s Bridge as a natural defense.

That effort was generally unsuccessful. The battle ended with Colonial troops falling back after a day of fighting. British general Lord Charles Cornwallis took up residence in the house that’s still on the property for about a week while he planned his march northward which ended in the British capturing Philly about a month later.

But there’s a much richer history here beyond the few days the Cooch’s property turned into a battlefield.

“There’s this connection between past and present as you’re learning not just about the battle, not just about Revolutionary War history, but about all these other elements of Delaware history,” Watchorn said. “Whether it’s the people, the land, transportation in Delaware, the property and all of it, it’s an incredible resource.”

The industrial history stems from Cooch’s grain mill, which was cutting edge at the time.

“When he built the mill in 1792, all of the millers from Brandywine Village came to see what he had done,” Catts said. “Brandywine Village was the prominent milling community in the mid-Atlantic at that time, they all came to see what he put in that mill because it was innovative and exciting.”

As for its role in the history of American transportation, the property sits on Old Baltimore Pike, once a part of the main north-south road linking the colonies called the King’s Highway.

“Old Baltimore Pike was the most important road in the United States. It linked Philadelphia to places south. I-95 does the same thing,” Catts said. “A mile south of I-95 is the road that used to do that. This place is on that road. It was this important spot.”

Protected property

Over eight generations, the family has been very protective of the land for more than 200 years. That means there are pieces of history hidden throughout the property, including lots of remnants from the battle still buried throughout the area.

“There’s musket balls [and other] period artifacts that would say that you’re in the battlefield,” Catts said of the material still hidden underground hundreds of years after it was used as a staging area for some 15,000 British troops.

“You have thousands of people on this land. They’re going to leave behind a signature and so it is all still potentially out there,” he said. As someone who studies lots of battlefields up and down the East Coast, “This one’s in pretty good condition,” Catts said.

He’s quick to point out that the site remains under archeological protection by the state which bars anyone from digging in the area for any reason.

The land will continue to be protected under a 2002 conservation easement agreement Ned Cooch signed with the state to protect it from development, but there’s some pressure from realignment of the I-95 interchange with Route 896 that’s adjacent to the property.

Plans call for a massive overpass to more quickly connect drivers between the two roads which Catts fears could impinge on part of the Cooch property in close proximity to the 1792 dam.

“We have some concerns about the new I-95 ramp that is being proposed and the visual effect that will have on the bridge,” he said.

There’s also concern on the southwest end of the property with the Dept. of Transportation’s plans to widen Old Baltimore Pike.

“You are in the National Register Historic District here, so those things need to be taken into account with whatever it is DelDOT is going to do,” Catts said.

Protecting the land and restoring the house and other buildings is top priority for the Friends group. Further down the road, they’d like to see the Cooch property connected by walking or biking trails to other nearby parkland, including a pair of parks run by New Castle County.

Just across 896 sits Iron Hill Park, a 335-acre parcel which sits on land that was also once owned by the Cooch family. Gen. Washington likely used Iron Hill as a lookout point to monitor the arrival of British troops coming ashore in nearby Elkton, Maryland after sailing up the Chesapeake Bay, according to Catts.

A few miles to the south, the county’s Glasgow Park has grown into a popular destination for outdoor activity with ballfields, a hiking trail, and even a skateboard park. There’s nearly a straight line of undeveloped land between the Cooch property and Glasgow.

Watchorn envisions a trail connecting Iron Hill and Glasgow Park with the Cooch’s Bridge battlefield in the middle.

“We think there’s tremendous potential to see the site not only as a historic site, but as a site of possibly passive recreation,” he said. “There’s an opportunity to link properties and in that way sort of make it a fully public site again that belongs to all of us the way it used to hundreds of years ago.”

Watchorn and the Friends have been hosting private tours of the site in hopes of helping more people catch their vision of what Cooch’s Bridge could be.

“One of our visitors just last week said as they were kind of stargazed by everything they were seeing: ‘Philadelphia has Valley Forge, Delaware can have Cooch’s Bridge.’”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.