Ghosts from a haunted past emerge in photographs of African American history

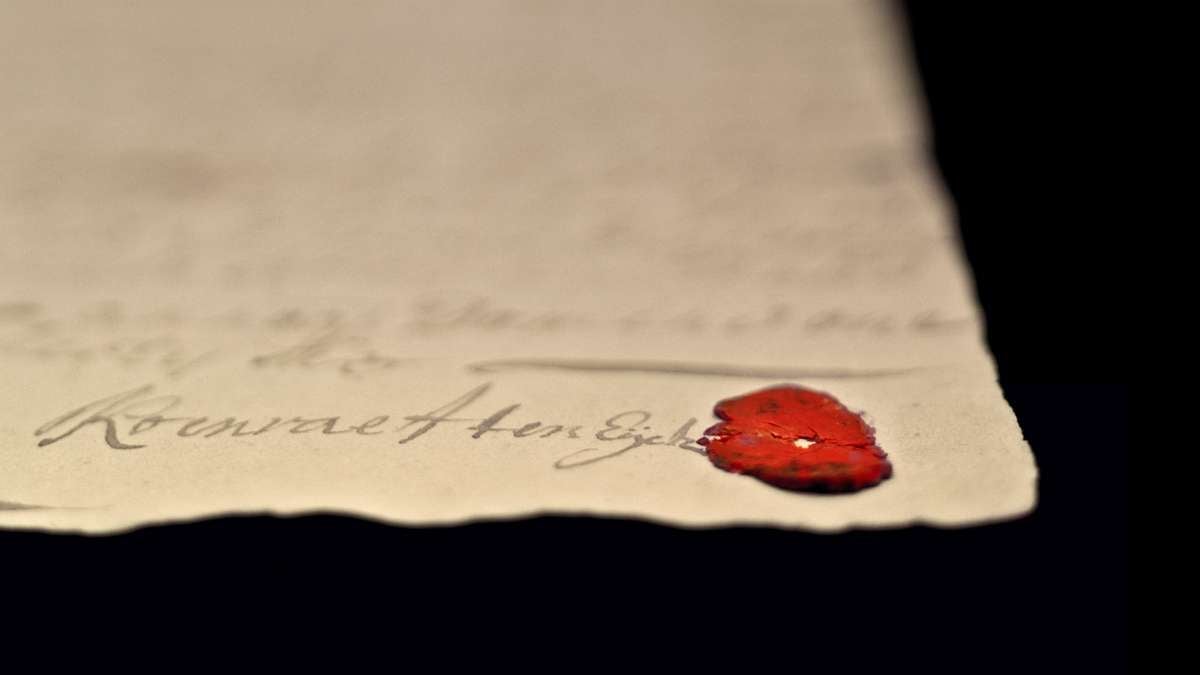

A lock of hair on white paper with the name Frederick Douglass penned within its creases; a colorful quilt folded over so the name of the maker, W. Black, stitched in black thread, is visible; a slave bill of sale with red sealing wax – these items remind us to “never forget.”

These artifacts, visually presented in a space as quiet as a funeral home, tell the stories of a people who are past. Viewing the 36 photographs in Wendel A. White: Manifest, on view through May 10 at the New Jersey State Museum, is like paying respects to the dead.

The images continue White’s explorations to “seek out the ghosts and resonant memories expressed in various aspects of the material world,” he says. “I am drawn to the stories dwelling within a spoon, a cowbell, a book, a photograph, or a partially burned document. The remnants present in material culture are haunted with spirit — the idea that the object was touched by some body.”

The objects, though small, become powerful in these large-scale images. A rusty doorknob with peeling paint becomes a thing of beauty, radiating something holy in the way it is lit. There are tintypes of unknown African American soldiers and a yellow flaking AME Church Journal from Riverton, N.J. A lunch box, a slave collar, a class ring, a drum, a photograph of a lynching pasted onto a page of an album with the caption “Rioters on the South Side Court House, Sept 28, 1919.”

“These representations of objects, documents, photographs and books, stored in cases and file cabinets, are imbued with the bigger story they tell,” says Curator of Fine Arts Margaret O’Reilly. “White’s Manifest project transforms the usually small and often fragile remnants of the struggle for freedom and equality into images larger in scale than the original subjects.”

The Distinguished Professor of Art at Richard Stockton College and winner of numerous awards including a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship is known for his landscapes of African American cultural history, including a series of portraits of black towns in southern New Jersey and “Schools for the Colored,” a portion of which was recently exhibited in the Gallery at Rider University.

The word manifest: it makes us think of Manifest Destiny, or the manifests of slave ships that kept track of their human inventory. “All of those exist in a way in which the word ‘manifest’ is meaningful,” says White.

The project began when White was a visiting faculty member at the Rochester Institute of Technology and discovered some of these objects in the collection of the University of Rochester, including the hair sample from Frederick Douglass and the first book Douglass bought after becoming a free man.

“It got me thinking about what is held in public collections related to African American history,” says White, a resident of Galloway Township. “My projects in the past 25 years all connect to the black community.” Through an artist residency in Omaha White looked at different collections in the state historical society, then in western New York, the Rutgers library, private collections, Cape May County Cultural & Heritage Museum, and in Eatonville, Florida. He received funding from the Andy Warhol Foundation as part of a larger project celebrating the work of Zora Neale Huston.

Born in Newark in 1956, White first became interested in photography at Montclair High School. His parents had separated when he was young – neither was involved in the arts, and they didn’t discourage his interests. Holidays were spent at his grandmother’s house in Philadelphia where he heard stories about the family farm in Bertie County, North Carolina. He would photograph large family reunions, and a growing interest in the photography of Bruce Davidson and Gordon Parks inspired him to frequent galleries in New York. He studied at the School of Visual Arts in the mid to late ‘70s, and earned his master’s degree at the University of Texas in Austin, another white male bastion.

After graduate school, while living in Brooklyn, White continued shooting while working in a camera store, where he met influential photographers who made important connections for him. He patched together different jobs: adjunct at the School of Visual Arts, teaching at Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital, organizing photo shoots at Essence magazine. He joined the faculty at Stockton in 1986.

The photographs in Manifest were made with a large format view camera, placed close to the object, enshrouded with black velvet. They were shot on film that is scanned and printed digitally. Only available lighting was used. The objects are photographed on site – they typically cannot be removed from the collection.

“A photograph is a portal in time,” says White. “We look at the photograph and it takes us back in time to when the photographer was behind the lens. We’re encountering objects in the past and responding in the present.”

White will lead a gallery talk May 8 at noon — Wendel A. White: Manifest is on view through May 10 at the New Jersey State Museum.

_________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.