From auto house to church: A view into Kingsessing’s past

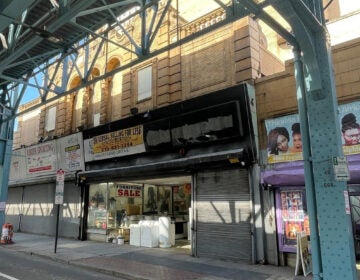

On Elmwood Avenue, halfway between 58th and Alden streets, what looks like a small brick barn sits far back in a large lot that is otherwise empty. Since this barn was built in the early 20th century, this area of Southwest Philadelphia has grown up around it. Today it sticks out from the row houses and an adjacent daycare, a relic from another era, offering clues to the neighborhood’s past.

Kingsessing isn’t a neighborhood most Philadelphians think much about. The houses hide under years of abuse and neglect, but what is not widely appreciated is the neighborhood’s rich history – stories waiting to be told if you peel back the layers of time. Consider the example of this small brick barn (actually an early 20th century “auto house”) that is today used as the Church of Shekinah Glory Apostolic. Originally the auto house was constructed as an outbuilding on a large estate owned by a wealthy family, but over time the auto house has been reused as the neighborhood changed around it. As part of a research project at Penn, I went digging through the Kingsessing’s past by examining the changes and additions made to this small auto house, from its place as part of a sprawling estate to its contemporary use as a church, and found that its adaptations mirror the transformation of this area of the city as it developed.

Beginning in the mid 1700’s, the area of South Kingsessing was divided into large tracts of land held by wealthy landowners. Factories, which would come to characterize this area of the city over the next 100 years, were just beginning to develop to the east and stretched south along the Schuylkill River. Bartram’s Garden was already established to the north.

The Gibson family originally settled in this area in the 1720s on more than 300 acres of land along the Schuylkill. Their land was passed down through the generations, but by the 20th century it was slowly being subdivided and sold off for development. By then, Kingsessing’s old estates were surrounded by industrial uses and rowhouses began to dominate the landscape.

One of the main players in the redevelopment of Kingsessing was Samuel Dixon Gibson. He was among the last owners to retain a large tract of land in the area. After obtaining degrees in law and medicine from the University of Pennsylvania Dr. Samuel Gibson Dixon became the first Commissioner of Health in the state of Pennsylvania in the late 19th century. One of Dixon’s obituaries in 1918 described his family estate in Southwest Philadelphia this way:

“… Born in Philadelphia, March 23, 1851, in the old homestead on the banks of the Schuylkill River below Bartram’s Garden where the family settled upon its arrival in this country, April 17th, 1721 and where members of the family have lived ever since that date.”

During a meeting in memory of Samuel Gibson Dixon in 1918 at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, a pamphlet describing his life described his family homestead in Kingsessing:

“The interesting home owned and lived in for six generation of his mother’s family called “Waverly,” where he was born, still belongs to them. Adjoining Bartram’s Gardens the three hundred acres reached the Schuylkill River, where, from their own wharf, they shipped the farm products and caught the shad in the spring, justly prized from those waters. The city’s growth has destroyed these advantages which the earlier generations enjoyed, but it is rare that any home in this county remains in the possession of the sixth generation of any family.”

In his last decades of life Samuel Dixon Gibson began subdividing his family’s large estate to sell to middle class families and developers. These early 20th century developers built small twin and attached row houses to house families working in the area’s growing industrial manufacturing facilities. However, during the first transaction, Samuel Dixon Gibson illustrated his desire to keep the area residential and attempted to stop the encroachment of factories by adding a clause to the land deed stipulating:

“No slaughter house, skin dressing establishment, glue, soap, candle or phosphate manufactory, oil refinery, distillery or other building for offensive use and occupation shall at any time be put or erected on premises.”

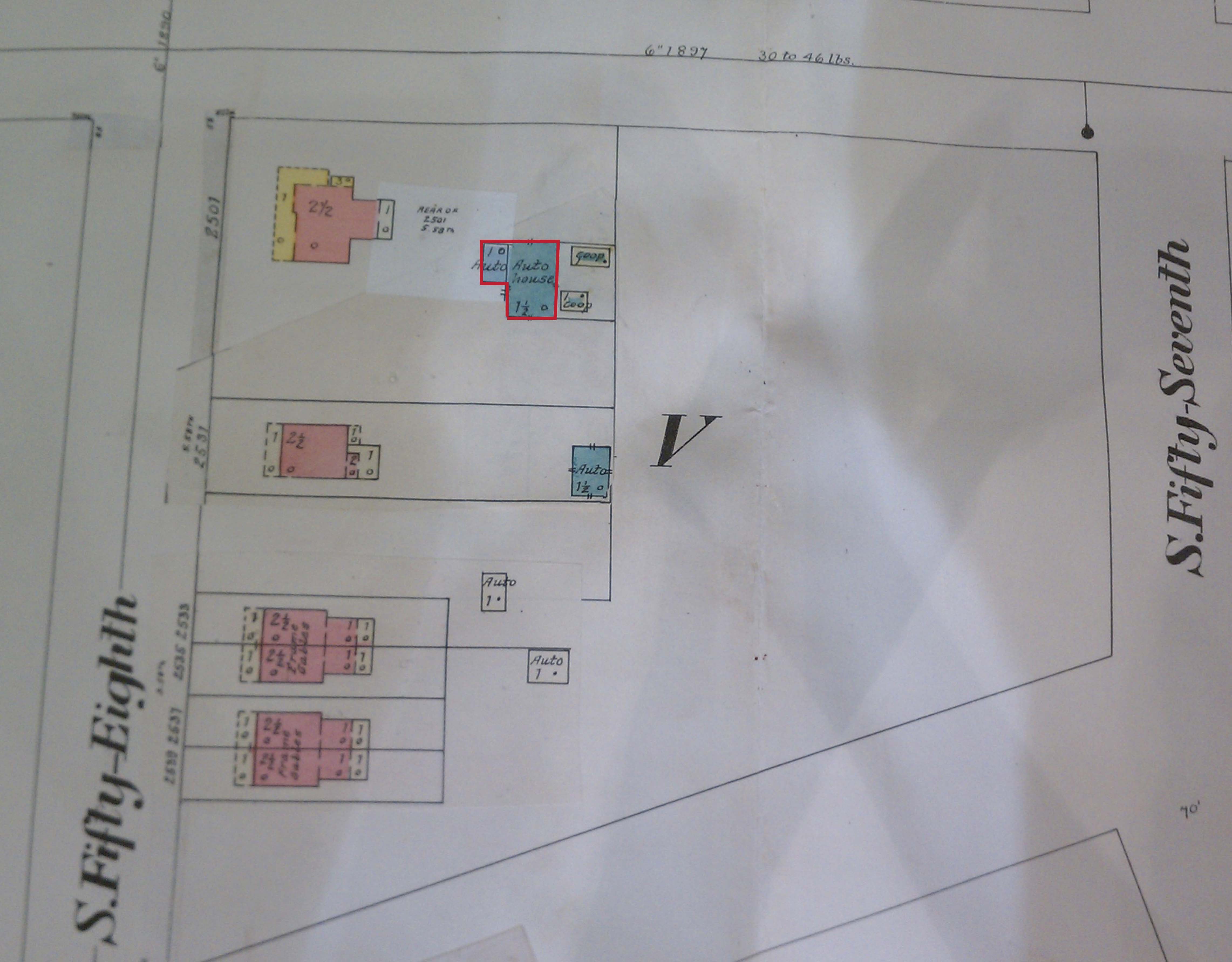

The lot where the auto house currently stands was sold by Samuel Gibson Dixon to Edward Cullen in 1890. At the time, an estate house on the property was the only structure built on the land at the corner of Elmwood and 58th Streets. The land then passed to Peter Thomson in 1904 who constructed the auto house in the back of the lot between 1904 and 1910 to face an alley leading to Elmwood Street. For the last century the little brick auto house has watched its corner of Kingsessing change radically.

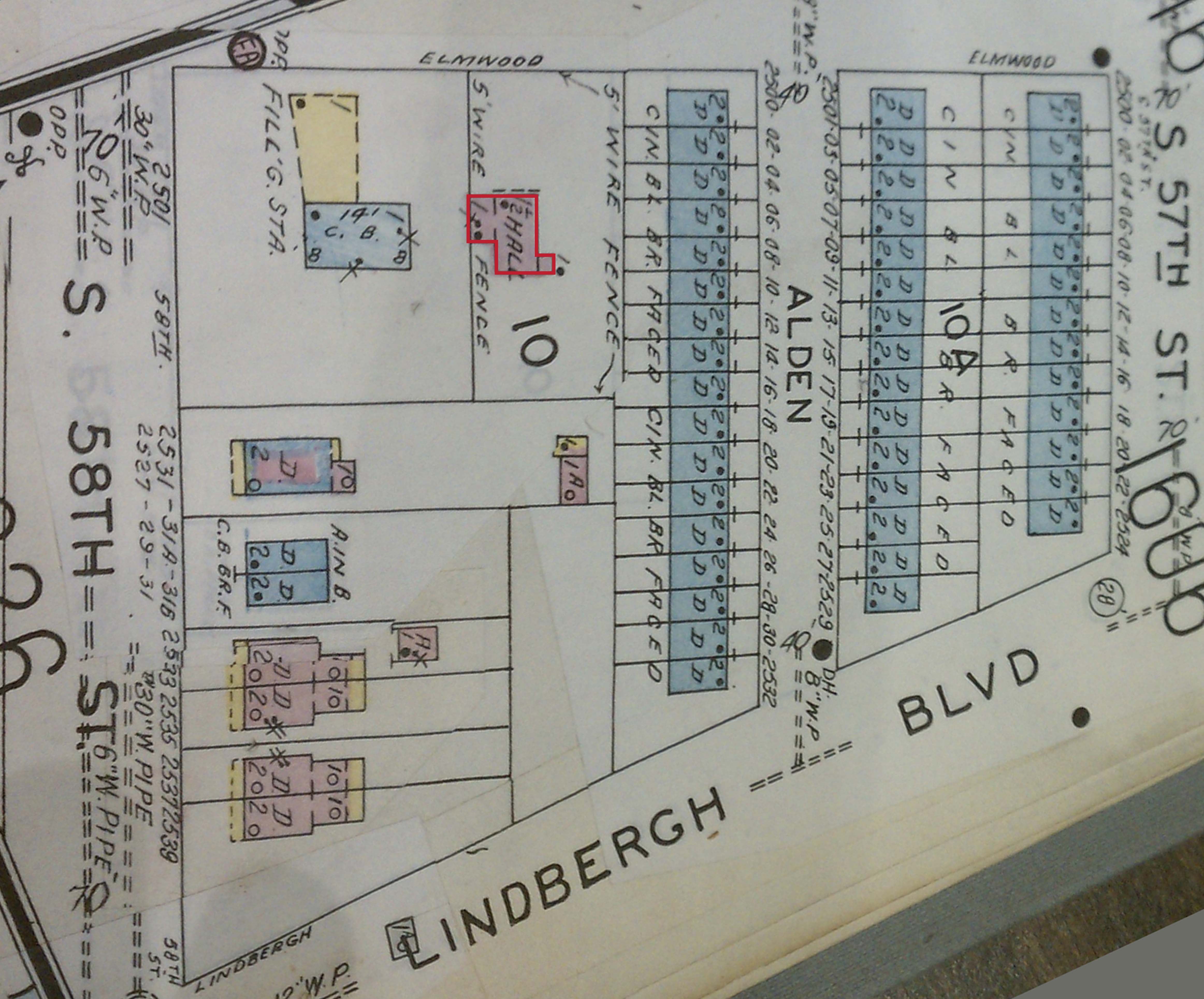

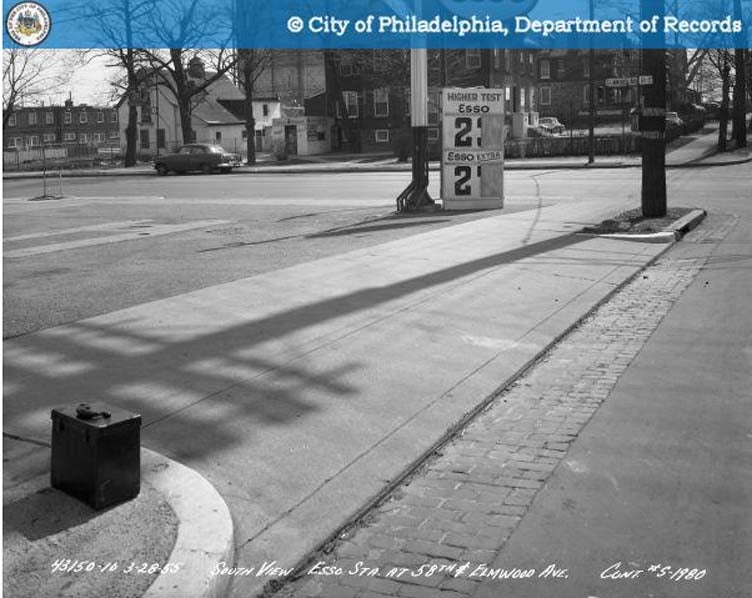

After his death in 1918, Samuel Gibson Dixon’s widow Fannie continued subdividing and selling off the family estate to commercial developers. It was quickly transformed into the rowhouse landscape we recognize today. She sold the land north of the auto house to Burns & Lange Inc., who developed the property into small, two-story rowhouses between 1951 and 1952. By 1926, Peter Thomson sold his property to Jacob H. Longnecker who later died in 1947 owing debt to The Tradesmen’s National Bank & Trust Co. Longnecker was the last owner to use the house as a residence. As soon as the bank took ownership in 1947, they subdivided the land into two parcels, selling the one containing the auto house to the Belmar Community Band and the other to Tide Water Realty Company. The original estate house at the corner of Elmwood and 58th Street was demolished by Tide Water Realty and became a filling station. But the Belmar Community Band converted the auto house into its meeting space. Presently, there is little evidence of the country estates that once characterized this area of Southwest Philadelphia.

Today, the Church of Shekinah Glory Apostolic and its pastor, Gary Shackelford, own the small auto house. It is used as a meeting place for the congregation. The immediate surrounding neighborhood is still a mix of attached row houses, industrial buildings and a large park. Two additions have been added to the southwest side of the structure, nevertheless the original design of the house is still discernable. Earlier window openings have been filled in with brick or concrete, but the outlines of the carriage doors still endure showing its original use as an auto house.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.