Four ideas for fixing parking politics from Donald Shoup

The High Cost of Free Parking should not be as popular of a book as it is.

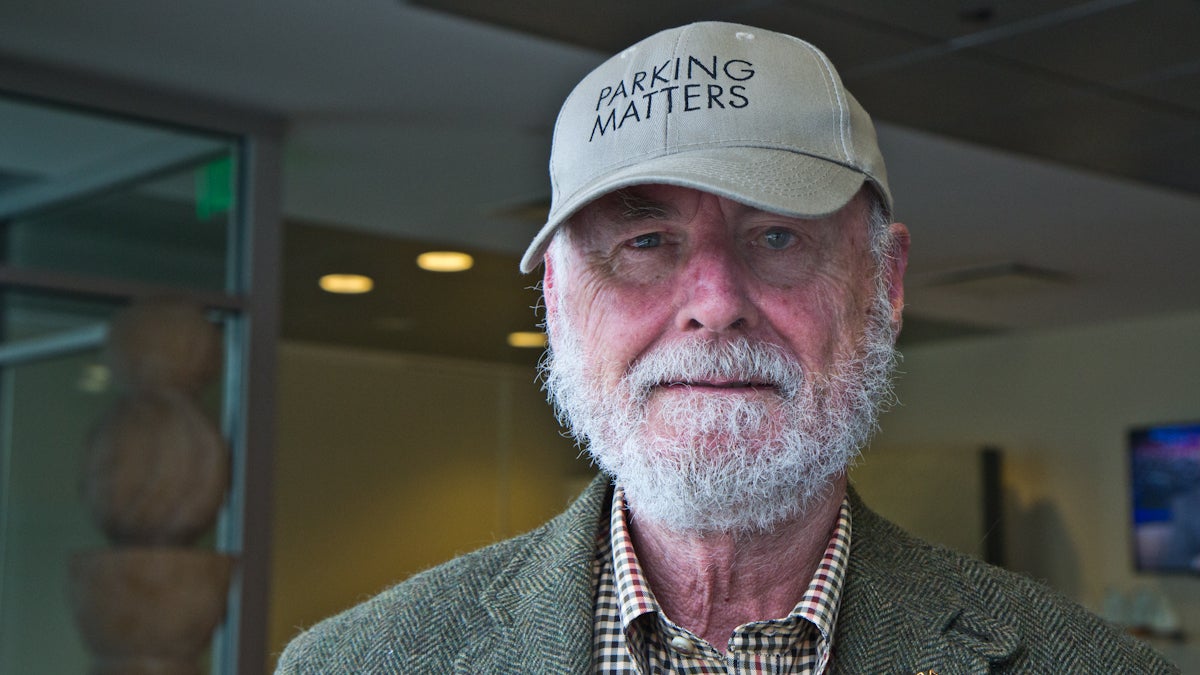

It is a nearly 600-page, 20-year old collection of academic research by UCLA professor Donald Shoup on the economics of parking. But for a narrow slice of urbanists, Shoup’s tome has achieved a sort of cult status.

Shoup was in town last week for a breakfast forum hosted by the Delaware Valley Smart Growth Alliance, a group of developers, architects, and public officials from around the metro area, and he made an appearance on WHYY’s Radio Times while he was in Philadelphia.

In each of these forums and a Q&A with PlanPhilly, Shoup made an exhaustively-researched case in support of a simple concept: Cities should charge the “right” price for curb parking—-the price that keeps one or two spaces open on each block—-and spend the proceeds on public improvements around the metered areas. American drivers, he observes, pay a small fraction of the cost of the parking they use, when they pay at all. Most of that cost is spread instead to all of us, with deleterious impacts ranging from increased traffic congestion to excessively auto-oriented land use and reduced housing affordability.

Cities, Shoup contends, should not attempt to manage parking through minimums—-a practice he likens to a pseudoscience—-and should focus instead on setting the right price for curb parking.

Recently, parking reformers have been racking up wins in more cities, including Philadelphia, where the 2012 zoning reforms rolled back parking minimums for single family homes and businesses, and reduced them for multifamily buildings. Those changes are far from settled business though, and will continue to rest on shaky footing, as the challenges for parking reformers remain political.

Shoup’s niche popularity is due in part because his book was as much analysis as it was an actionable policy agenda with a credible political path forward, either through growing a political constituency for economizing parking or shrinking the constituency for parking. It’s not just a treatise; it’s a road map.

So where would Shoup have us go? Four stand out as especially interesting possible destinations.

Parking Benefit Districts

Parking meter revenue destined for a city’s general fund may as well vanish into thin air, as Shoup put it in his presentation for the Delaware Valley Smart Growth Alliance last week.

Parking meters can generate substantial revenue, but people who pay for parking feel disconnected from how they might benefit from the spending of that income. A Parking Benefit District—-similar to a business improvement district, but funded by parking meter revenue—-changes the game by spending the meter money in the area where it’s collected, the more local the better. The Parking Benefit District (PBD) concept is really the archetype of a Shoupian solution.

Businesses are often wary of paid parking because customers find it so distasteful, but when the money is spent on projects that make their own commercial corridors more attractive, businesses tend to be supportive, Shoup says. As I wrote in my explainer on PBDs for Keystone Crossroads, when cities hold out the prospect of a dedicated revenue stream for neighborhood project, some businesses and neighborhood groups become more supportive of parking meters.

PBDs range widely in the kinds of projects their revenue can be spent on, from storefront improvements and sidewalk repairs, to multimodal transportation or public safety services. The key is for the spending to be visible, and for the meters to effectively communicate the connection between meter revenue and public improvements. In Old Pasadena, the nation’s oldest parking benefit district, a sign on the meters reminds payers “your meter money makes a difference.”

“If it says right on the meter that your money pays for sidewalks, street trees, and street cleaning, and when you get out of your car it looks immaculate, the people parking and the merchants will see the benefit,” Shoup says.

At last week’s panel Andrew Stober, former chief of staff at the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities and now the VP for Planning and Economic Development at University City District, pointed out that there are challenges for this idea in Philadelphia. The city charter requires that all revenue go into the general fund, making it difficult to cordon parking revenue off for dedicated local spending. The Philadelphia Parking Authority is controlled by the state, making it difficult for parking reformers to influence policy there, and a state formula determines the distribution of parking revenue between the city and school district, after the PPA collects its overhead.

There would be a lot to untangle to make this work in Philly, but figuring out a workaround for the charter issues could pay off if it unlocked a new revenue source for Kenney’s commercial corridor plans.

Parking Permit Blacklists

The root cause of most neighborhood parking disputes is fear of competition, so Shoup opts for mollifying the opposition through solutions like parking permit blacklisting as an alternative to minimum parking requirements. Many drivers in Greater Center City became accustomed to finding easy, free curb parking close to home during the years when Philadelphia’s population was shrinking. But now that the population is growing and neighborhoods are repopulating, that’s all changed. When new buildings go in, some of the residents bring cars, and they want to use the same curb parking as long-time residents.

Shoup generally prescribes overnight parking permits for residential areas (distinct from Philadelphia’s all-day residential permits) but that’s no help in areas where all-day residential permits already exist and have outstripped the supply of curb parking spaces.

In those cases, Shoup recommends a parking permit blacklist for new buildings that don’t provide off-street parking. In this scenario, PPA would keep a list of the addresses of new car-free buildings, crosscheck new permit applications against the list, and deny permit requests from residents of those buildings.

“If you’re in a permit district, and new residences don’t have any permits, then you can’t say that it’s going to create any competition for ‘my’ parking,” Shoup explains.

It’s not pretty, but it essentially gives long-time residents exactly what they want—-exclusive access to nearby curb parking—-without conscripting non-drivers into paying for other people’s parking.

Parking Cash-Out

Employer-paid parking is like a matching-grant for driving to work, says Shoup, juicing the demand for parking at work. If you choose to drive, your employer will cover your parking. This practice is supported by a federal tax expenditure for up to $250 a month. (Congress recently increased the transit benefit to parity, up from a previous cap of $130 a month.)

Transit Center has called the tax benefit for parking a $7.3 billion subsidy for traffic congestion with no decipherable transportation rationale, but rescinding the tax exemption would be political poison. However, “Shoupistas” in California figured out a clever hack to the system in 1992 with the state’s “parking cash-out” law, which changes employees’ transportation incentives.

Under the law, employers are required to provide employees who qualify for employer-paid parking with a choice between the parking subsidy and its equivalent cash value.

Crucially, this leaves no one worse off. Employees who wish to continue parking at work can do so, but they also face a tempting choice to collect a few hundred more dollars a month in pay. The law only applies to off-site parking spaces that employers rent, so there are no sunk costs for employers to cover if employees opt out of the parking benefit.

Unlimited Access Transit Passes for Universities

The relationship to parking is a bit of a bankshot, but the Unlimited Access pass idea is similar to parking cash-out in that it aims to reduce parking pressure at work and school.

SEPTA currently has a discounted TransPass available for university students, but the discount is just 10%, and the rate of uptake among students is only about 3%.

Shoup’s Unlimited Access pass concept is distinct from this because students automatically receive an unlimited transit pass as part of tuition, paid for by an added transportation fee, which is sometimes subsidized by the university. (We’ve written previously about Pittsburgh’s program, where, for $180 a year, students and faculty at major city universities get unlimited access to transit, and there are dozens more of these programs across the country.)

“Some cities say that if you don’t require parking, then you have to buy transit passes for all the residents,” he says, “Some transit agencies offer apartment house transit passes, and they don’t cost as much as a regular transit pass because a lot of the people don’t use them as often.”

These programs grow the constituency for transit, which can help transit agencies build a case for funding, and shift the pressure off universities to try building their way out of parking demand problems. Transit agencies have to be the first to offer the program though, Shoup says, and shouldn’t wait around for universities to ask for it.

“I think the transit agencies are negligent, because here is a great opportunity for them. Students ride the bus, but they don’t dip into their own pockets, they dip into the university’s pocket. And wouldn’t you like to have someone subsidize what you sell?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.